“I dearly love her. She’s such a great person, always interested in people personally and very professional about her work.”

This excerpt from Jim Henson’s notes kept during production of “The Muppet Show” and published in the invaluable 1993 book, Jim Henson: The Works, affirm the late Muppet creator’s deep admiration of his frequent collaborator, Julie Andrews. Few artists throughout human history have cheered up the world as exuberantly and meaningfully as these two icons. Just as the Muppets gained global popularity in the aftermath of the Vietnam war, richly satisfying audiences’ hunger for innocence and joy, Andrews’ astonishing singing voice provided much-needed comfort during the turbulent era of WWII. In her stunning first memoir, 2008’s Home: A Memoir of My Early Years, Andrews recalls observing the power of music when her stepfather calmed citizens huddled in the Underground Stations during the London Blitz by performing songs on his guitar. It’s impossible to read this passage without being reminded of the harrowing climactic sequence in Robert Wise’s 1965 masterpiece “The Sound of Music,” where the von Trapp family holds their collective breath while hiding from the Nazis’ flashlight beams.

Andrews’ portrayal of Maria von Trapp remains my favorite performance in all of cinema. Ever since the musical’s Broadway debut in 1959, countless actresses have tried to capture the benevolence and uncynical beauty of Maria with varying degrees of success. With Andrews, it never felt like an act. There was no irony in how she regarded the children as if they were her own, nor in how she grew ashamed of her repressed feelings for their father. Just look at her during the scene when Captain von Trapp dances with her and they pause as their eyes lock, sharing a wordless discovery of the love that has stealthily blossomed between them, causing her to break away in a haze of confusion. The multitude of emotions expressed in that single, fleeting moment is absolutely breathtaking. Roger Ebert once wrote that nothing moved him more deeply in a film than “goodness and kindness,” and Andrews embodies both qualities with such radiance that she positively glows. Yet it’s the feisty and occasionally neurotic humanity she infuses into every scene that prevent them from turning saccharine.

Part of what makes Andrews’ latest memoir released last October, Home Work: A Memoir of My Hollywood Years, such a euphoric read are her recollections of what it really felt like to film some of the most beloved moments ever captured on celluloid. Consider this hilarious excerpt where she recounts the sheer difficulty of staging what would ultimately become the most blissful opening image in movie history…

“I began my walk, and as I did, the helicopter rose up and over its cover. It came at me sideways, looking rather like a giant crab. A brave cameraman named Paul Beeson was hanging out of it, strapped precariously to the side where the door would have been, his feet resting on the runners beneath the craft. Strapped to him was the heavy camera equipment. As the helicopter drew closer, I spun around with my arms open as if I were about to sing. All I had to do was walk, twirl and take a breath.

This required several takes, to be sure that both the helicopter and I hit our marks correctly, the camera was in focus, there was no helicopter shadow, and that everything timed out. Once the take was complete, the helicopter soared up and around me and returned to its original position. At that point, I’d run back to the end of the field to start all over again, until Bob was satisfied that he had the perfect take.

The problem was that as I completed that spin and the helicopter lifted, the downdraft from the jet engine was so powerful, it dashed me to the ground. I’d haul myself up, spitting mud and grass and brushing it off my dress, and trek back to my starting position. Each time the helicopter encircled me, I was flattened again. I became more and more irritated—couldn’t they see what was happening? I tried to indicate for them to make a wider circle around me. I could see the cameraman, the pilot and our second unit director on board, but all I got was a thumbs-up and a signal to do it again.”

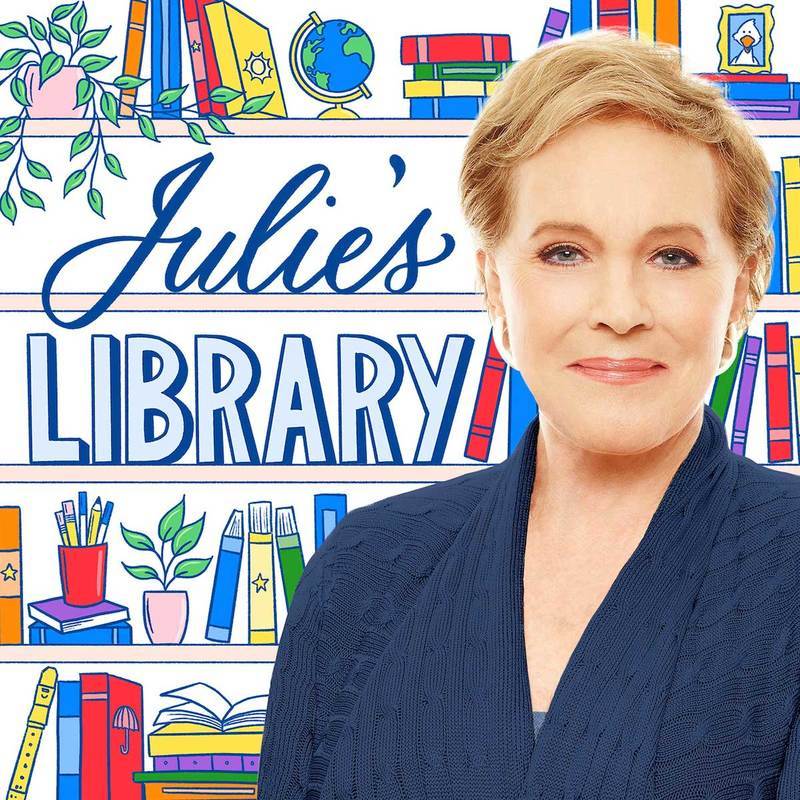

Andrews’ fierce resilience was put to the test in 1997, when a botched surgery brought her singing career to an abrupt end. It was her multi-talented daughter and “That’s Life!” co-star Emma Walton Hamilton who encouraged her to embrace new ways of using her voice, particularly through writing children’s books. Thus began an extraordinary new chapter of Andrews’ life that could very well form the basis of a third memoir. In 2017, she and Hamilton continued to nurture young minds by executive producing the marvelous Netflix series, “Julie’s Greenroom,” which introduces kids to the arts and is sorely deserving of a second season. I was so impressed by its mixture of inspired puppetry (courtesy of The Jim Henson Company) and insightful educational segments that I penned a rave review explaining how the show offers one of the best defenses I’ve seen for saving the National Endowment for the Arts. On the very day Andrews and Hamilton spoke with RogerEbert.com early last month, The Creative Coalition called on Congress to increase funding for the NEA, which our president is planning on eliminating, according to his 2021 fiscal year budget. “Greenroom” guest star Tituss Burgess is among the celebrities that comprise the coalition’s #RightToBearArts delegation.

Andrews was originally scheduled to receive the 48th AFI Life Achievement Award this past Saturday, April 25th, until it was postponed due to COVID-19. Instead, she and Hamilton have been working to ensure their latest project, which had been tentatively scheduled for a June release, will be ready to premiere this Wednesday, April 29th. It is a children’s literacy podcast entitled “Julie’s Library” that promises to bring great comfort to families during this period of isolation. Produced by American Public Media, the weekly program will consist of Andrews and Hamilton reading their favorite children’s books, while visited by special guests (including kids), as each narrative comes alive with the aid of sound design and music (you can subscribe to the podcast here). The first six episodes will be released one by one every Wednesday starting this week, with more due to arrive later in the year.

When Andrews appeared on “Good Morning America” in late March, she noted how the sense of unity that has emerged during this pandemic, where we’ve kept ourselves at home in order to protect those most susceptible to the virus, is reminiscent of what she observed in England during WWII. I cannot imagine a better way to pass the time in quarantine than by reading Andrews’ latest memoir, tuning into her podcast and binging her Netflix show, not to mention her beloved films (“Mary Poppins,” “The Sound of Music” and “The Princess Diaries”) currently available to stream on Disney Plus. In the following conversation, Andrews and Hamilton spoke with me about their numerous collaborations, while sharing their own cherished memories of Jim Henson and the Muppets.

Julie, you are a light on this earth in every sense of the word, and what these memoirs illustrate is that the light you radiate was hard-earned. How have you managed to maintain your optimism amidst difficult times?

Julie Andrews (JA): For my entire life, I have always seen the glass half full rather than half empty. When I was a youngster living with my family, I felt truly fortunate, particularly as our lives got a bit better and we became a little less poor. I was always hugely grateful when it seemed like we didn’t have to go back to any of that unhappiness. My gratitude has always come through more than anything else. How would you explain it, Emma?

Emma Walton Hamilton (EWH): I think you said it perfectly. She is the ultimate optimist.

JA: It’s not that I’m not a realist. I am. I guess, having reached this age, I’m grateful, but then again, I always have been. In my younger days, I was obviously very scared about whether I could accomplish anything, and I’d just be so grateful when I did or I got help.

EWH: You’ve always been willing to look on the bright side. In some ways, I think it was a coping mechanism for you when things were challenging to stay positive—

JA: —and focused—

EWH: —as a way of getting through.

JA: I think my lovely dad—the schoolteacher and the nature lover and the book reader and so on that he was—focused me a great deal. On one side of my family, I had my wonderful, colorful mum who was all full of life and full of passions, and yet, she was sad. My dad was the rock who really got me out of my crazy world, if one would put it that way, and into a very sane world of beauty and nature. There was no doubt that his love for me was constant, and I was able to absorb that part of him, which was so helpful.

Would you say that keeping a diary served as a therapeutic tool throughout your life, and is it something you’d recommend younger generations to utilize in the era of smartphones?

JA: Well I don’t think it could hurt at all. Looking back on some of my diary entries was very enlightening. I’d suddenly realize how I felt about certain things. I always had diaries as a child, but there were great periods where I didn’t follow up on them or I got too busy. Around the same time that I began therapy, I started keeping diaries regularly again, and they helped me enormously. They allowed me to not only remember parts of my life, but also stay somewhat sane in some completely insane situations.

How has this literary collaboration between you both enabled you to create a singular voice on the pages of these memoirs?

JA: I give Emma the most enormous credit for that because she was such a help.

EWH: Over the years, we have written over 30 books together in addition to acting together in films and creating “Julie’s Greenroom.” My husband and I have also produced productions that mom has directed, so we’ve had lots of different opportunities to collaborate creatively—

JA: And to explore each other’s brains, really.

EWH: There is a mutual level of trust that I think is really the bedrock of our partnership and our relationship, and that allows us to go into complicated, emotional, difficult places—

JA: Not that that’s easy, by the way. [laughs]

EWH: But we know that we’ll take care of each other and respect one another throughout the process. That was the foundation of it. Generally speaking, our process of writing together is one of finishing each other’s sentences, but in the case of the memoirs, they are obviously comprised of mom’s stories, mom’s sentences and mom’s words. With Home and the first quarter of Home Work, we achieved that mostly through an extended interview process. After I had created a comprehensive timeline of all the significant events on any given day and any given week or month or year of mom’s life, we would talk through those. I would interview mom and ask her questions. Then we’d record those interviews and have them transcribed. We’d treat those transcripts—

JA: —sort of like a diary!

EWH: Exactly, as the basis for narrative, which we’d edit through. Once we got to the point in mom’s life where she began journaling more regularly, then we had those to draw from as well. In those cases, it was a process of reading through all those diaries and flagging sections where we felt that literally quoting them verbatim would lend the most insight to the reader.

JA: It’s quite daunting to do the memoirs, I must say. I love doing the children’s books, which are great fun, but with the memoirs, you always get so nervous. You want to share experiences that might be helpful, but you don’t want to hurt anybody. It was quite painful for me to be able to sort of let it all go, and realize that now it’s out there in the world, and there’s absolutely nothing I can do about it. You can’t edit the book in any way, shape or form.

One of the first things that Home Work will inspire readers to do is watch every one of Julie’s films that they’ve missed. Blake Edwards’ “Victor/Victoria” was ahead of its time in how it removed the stigma from issues of gender identity, and I felt you did the same thing with the gender neutral character of Riley on “Julie’s Greenroom.”

JA: That’s so lovely of you!

EWH: Thank you, that was our hope.

JA: I do think that “Victor/Victoria” was ahead of its time, too. Blake loved to break down barriers and think outside the box—and my god, with his comedy, he certainly did. But he was, first and foremost, a writer, and I must say I was astounded sometimes by his thoughts and ideas and his twists and turns. Other than “Some Like It Hot,” the film that Billy Wilder did, I think it was Blake who really broke the gender barrier, and he did it in a much more realistic way than Billy’s film did. Both movies also happened to be based on German films. [“Victor/Victoria” was based on Reinhold Schünzel’s “Viktor und Viktoria,” whereas “Some Like it Hot” was based on Kurt Hoffmann’s “Fanfares of Love,” which was itself a remake of Richard Pottier’s French film, “Fanfare of Love.”]

EWH: The thing about “Victor/Victoria” that is so beautiful is the fact that it’s a story about love having no barriers or boundaries. It’s just about loving who you love.

JA: And not feeling bad about it.

EWH: Yeah, and that was such a beautiful topic for Blake to tackle at a time when perhaps that conversation was not being had, or should’ve been had, as much as it is now. That was our intention with Riley as well, and it’s a subject that’s close to our heart.

JA: And we loved Riley. All those characters were so beloved.

EWH: I have a transgender nephew and I am keenly aware of the challenges he has experienced going through high school and so forth. It was important for us to have all the kids in “Greenroom” representative of as many different young people’s experiences as possible.

To me, “Julie’s Greenroom” recaptured the magic of “Sesame Street” during the years I grew up watching it by empowering the voices of young people while sparking their imagination.

EWH: We certainly wanted to spark kids’ creativity, that was very much a goal. We wanted to celebrate the arts, obviously, but more than anything, we wanted to find a way to make the arts feel accessible to kids across different cultures and economic boundaries and communities.

JA: There’s always a place to go, even down the road, where you can be part of the arts in some way.

EWH: We wanted to celebrate the fact that the arts are kind of the great leveler or the great neutralizer.

JA: We are both passionate about that issue. The arts, of course, are always in danger of disappearing because they are the first thing to lose funding. They are so nurturing and so necessary in our lives. We actually wish that our show had continued. I adored all of those puppets and I loved the duck too. [laughs]

You and the Muppets appeared on each other’s programs multiple times. I’d love to hear about your experiences of working with Jim Henson.

JA: Long before Henson came along, I had been considering doing children’s programming and thinking about what would grab them. I didn’t think quite as big as Henson did, but I thought that making a Saturday morning special, maybe with my friend Carol Burnett or someone like Lucille Ball would be so interesting. Then, of course, Henson came along and literally beat me to the finish line because he was so prepared and ready. It was wonderful that he just took the ball and ran with it. From then on, it was literally all about him, as it should’ve been.

He was an adorable man. I remember him being very tall and looking sort of like if Lincoln had dressed in a western costume of some kind. He had a very special hat and very special clothes, but not to make a statement, just because that was the way he was. He was lovely and gravely funny—so grave and then the humor would come out of him. I was doing a television special, and we invited the Muppet performers on before they really burst onto the waking world. I noticed that between setups, they’d still be performing different characters.

If they were working behind some kind of a wall or shelf where you couldn’t see them, you’d see their hands on the edge of the proscenium. Two sets of fingers would meet and talk to each other, and then one would knock the other one off. Even then, you knew that they were going to be huge. They were so easy to work with, and when it came to doing specials with them, it was the easiest thing in the world. So much fun.

EWH: It’s an amazing thing, Matt, to work with puppeteers. They are a unique culture unto themselves, and they are the most extraordinary people. They are so selfless—

JA: And shy.

EWH: Yeah, most often, quite shy and totally absorbed in the creation of this character while keeping themselves completely hidden. They never break character!

JA: And in fact, when I was working with a puppet, I never took note of the human being below the character.

EWH: I remember being a kid on the set when mom was doing her “Julie on Sesame Street” special with the Muppets. I have a photograph, which I love, of mom and Perry Como with the guests. We were all doing a still photo for posterity, just sitting on the steps of one of those “Sesame Street” brownstones, and in the photograph, all you can see are us and the Muppets. What I remember so clearly are all the puppeteers who were beneath the Muppets, whose bodies were sprawled across the brownstone set, but just out of camera view, creating this illusion. That was very much the case in “Greenroom” as well. We were working on a stage that was six feet above ground, so that the puppeteers could be at ground level with their arms above their heads—

JA: —looking at the monitors and operating the puppets on the decks.

EWH: Then mom was walking around on this high deck with these puppets, so there was always a duality. It was so fascinating to see one story going on above the floor, and a whole other story occurring below the viewer’s sightline.

JA: To observe how lovely the people who perform those characters are, all you have to do is watch what happens when children are present. Occasionally, a guest star or someone else would bring their kids onto the set, and even if they were shy or not happy that day, one of the Muppet actors would pick up their puppet, go over and engage the children quite easily. They would do this just because they could. The puppeteers would make these kids completely at ease and they’d chat it up with them. The children would always focus on the puppet and be instantly engaged, forgetting their fears. It’s such an interesting phenomenon, really.

EWH: They are some of the best people in the world, they really are.

Some of the biggest laughs in “Mary Poppins” occur when you play straight man to Dick Van Dyke with your exasperated expressions during the “I Love to Laugh” number. How were you able to sharpen your comedic instincts?

JA: I think it came from a certain self-confidence, but I know, more than anything in the world, that I was influenced by the years in vaudeville. I toured towns around England playing with all the great vaudevillians and comedians, and performed with them every night, twice nightly. All one did was watch the timing and the reactions of the performers. I didn’t realize I was getting such an education, but I really was. There is a lot of shtick that you can adopt from these wonderful people, all of whom had their own individual talents.

Speaking of confidence, one section of Home Work that had me laughing out loud is when you describe your puzzlement over the lyrics for “I Have Confidence,” and how it inspired Maria’s comedic movements, stumbling out of the bus as she sings, “With every step, I am more certain.” It’s such an intuitive approach that pays off brilliantly.

JA: Intuition definitely served me well, in that case. I honestly wasn’t sure about how to say a particular, small bunch of the lyrics because they don’t really make sense. So I thought, ‘Because she’s so scared and so frightened at this point, she’s out of her mind a little bit.’ I asked the director if I could play it that way, and he let me run with it. It was great fun and we used it. I think it was slightly created on the day of filming and also slightly planned.

I’m eager to hear more about “Julie’s Library,” your upcoming podcast focusing on children’s literature.

JA: We’re actually going through scripts for it right now, and we’ll be starting the week after next.

EWH: The podcast is with American Public Media and it celebrates children’s literature, mostly picture books. It’s a read-aloud podcast, and we’ll be celebrating at least one and sometimes two books per episode. We’ll have special guest visitors, with kids voicing and calling in, and we’ll have activities around the stories.

JA: We hope that the listener will feel like they are in a special place, listening to stories and snuggling down together.

EWH: Our hope is that it will be multigenerational and that families will listen together on car trips and waiting rooms and stuff like that. But the idea is also to have a social/emotional conversation around the themes that these picture books that we are reading generate.

JA: And of course, it is hard because we are choosing picture books that can be read aloud but not seen. So we are having to find books where the story comes out regardless, and then I hope that listeners will want to go out and buy the book.

Before we go, I must say that I was lucky enough to catch Julie’s 2005 directorial debut, “The Boy Friend,” onstage in Chicago.

JA: I enjoyed that so much, and I am doing a lot more directing these days because it is such a pleasure for me. It’s a way of giving back, in a way.

For more information, visit the official sites of “Julie’s Library,” The Julie Andrews Collection and Emma Walton Hamilton. You can subscribe to “Julie’s Library” here.