When Hank (Jeremy Gardner) isn’t looking around with an anxious glare, always in hunting mode, he’s daydreaming about his girlfriend Abby (Brea Grant). Hank’s memories, bright and sunny, present Abby as a loving, funny partner—all the more harrowing given that she’s currently missing. With just a note, she has disappeared from the family home that they’ve shared over the course of their ten-year relationship. There’s also a monster who attacks the house at night, forcing Hank to sleep by the door with shotgun in hand, but that anxiety isn’t as deep as the pain he feels about Abby getting up and leaving.

Written by Gardner, who co-directed with Christian Stella, “After Midnight” channels this state of mind for half a movie, and it can feel relatively narrow. The timing is padded out with some kooky monologues by his dopey, not-so-helpful friend Wade (Henry Zebrowski), who drinks from the mat at Hank’s bar, and an appearance by Justin Benson as an old-fashioned cop and sibling to Abby. The movie is almost so proud of its monster metaphor that it doesn’t dig into it; instead it’s more images of Abby, juxtaposed with Hank’s grungy shield. And despite the progressive physical wear that comes from Gardner’s beat performance, like whenever the monster pops up, “After Midnight” appears to be limited and let itself stay that way. At its worse, it risks losing the viewer with Hank’s shallow sulking and aimless bangs of the monster in the night.

But that’s not the last we see of Abby, a detail I share so that you too stick with the movie. She re-appears as if out of nowhere halfway through, and not long after the two clear things up about her disappearance. The scene unfolds with them waiting for the monster, for 13 minutes, sitting in the doorway on the eve of her 34th birthday. It’s a well-written, emotionally incisive volley of their different grievances, the microaggressions he thinks he can justly hold over her, and the melancholic clarifications she retorts about her own wants with her big picture in life, ideas he has previously looked past. He still struggles to look her in the eyes when she talks to him about serious notions of a future, of maybe living somewhere else than the middle of nowhere. This centerpiece creates a full picture of what has really been going on in their diverging, ten-year relationship; it’s the entire movie with no monster needed. It’s just these flesh-and-blood performances, and a camera that very, very slowly pushes into them—the most gentle but effective touch that filmmaking has to get us to pay attention to something staged like excellent theater.

This is the first passage in which I was deeply invested in “After Midnight,” and it makes the scenes before it slightly more worthwhile as creating unsuspecting anticipation. For all of Hank’s rosy flashbacks, this is the reality check. And for all of the ways that Gardner and Stella’s editing abruptly shakes Hank from his daydreams, while banking half of its movie on a monster waiting game, this is the long hard look. The movie evolves with this scene, in a way that only skilled storytellers could accomplish, and the ingenuity from directors Gardner and Stella makes the emotions all the more heightened in what plays out next.

In finding out what to do with these raised emotions, “After Midnight” can then fall short. Gardner and Stella are able to build upon simply representing the pains of a broken relationship, but Abby still feels like she’s more a subject of Hank’s gaze, or that he’s the recipient of her simplified one. She’s not a three-dimensional character, despite being played by Grant, who proves here (and with her script for “12 Hour Shift,” and the upcoming “Lucky“) that she has an expansive dramatic imagination. Instead of just being the gone girlfriend, Abby becomes the girlfriend who can wake up the man-child from his immobility, which itself is an overly pat storytelling way of addressing a more complicated beast within someone like Hank.

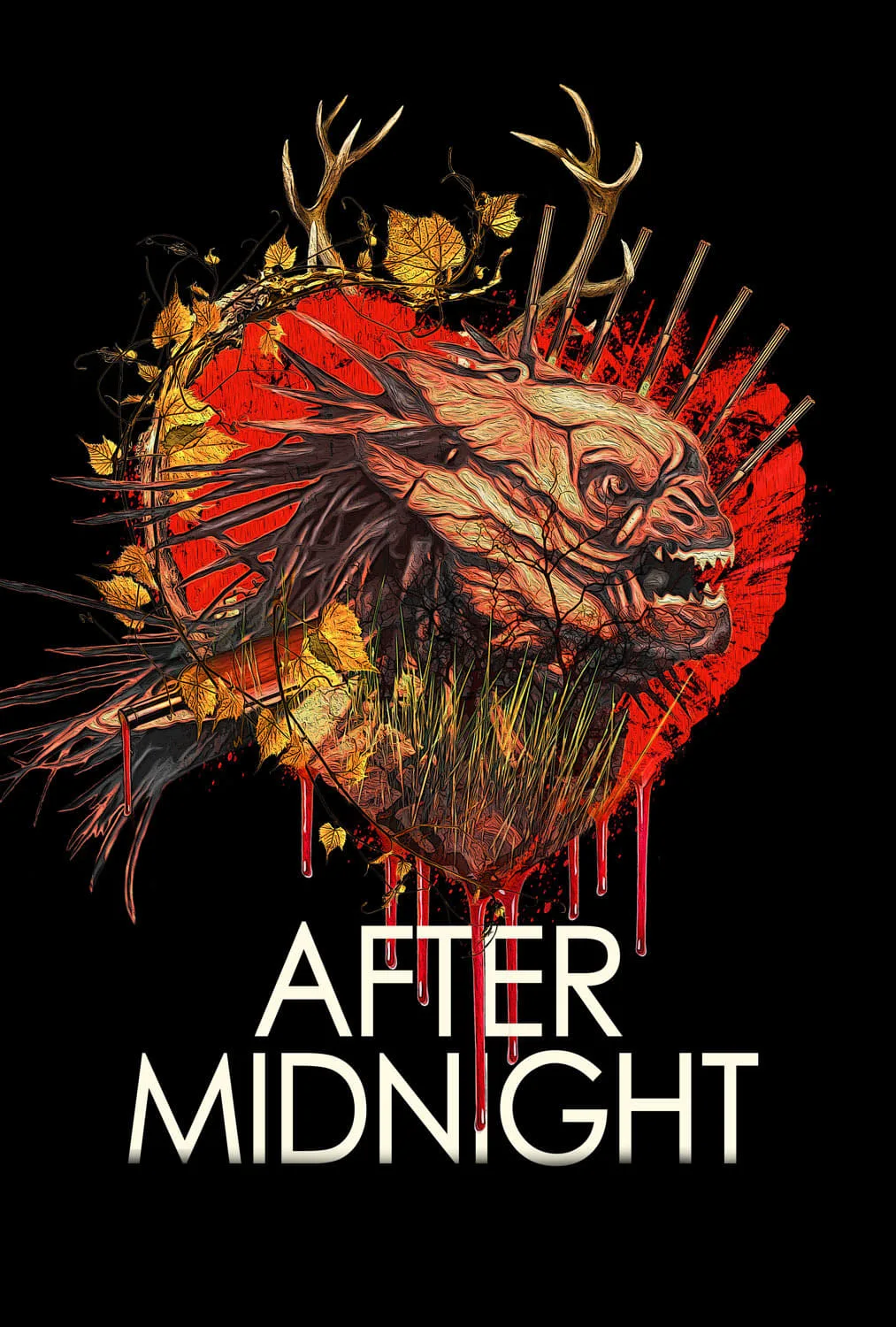

But here is a monster story with an exciting bait-and-switch, whose heart bleeds slowly like “Blue Valentine.” If the emotions don’t hit you, if the conversations don’t look like previous crossroads you’ve faced with a long-time partner, at least the ambition behind them will. And the final scenes are punchy, with a legitimate, winning jolt. The balance that “After Midnight” strikes between a two-hander and a monster story warrants a Valentine’s Day weekend look, and maybe even a scary conversation.

Now playing on Shudder.