Chicago has spawned any number of literary lions over the years, but if pressed to name the one that best exemplified the city, especially the areas and denizens who tended to be excluded from the tourist pamphlets, it would be Nelson Algren. His literary output may have been relatively slim—five novels and several collections of short stories and non-fiction pieces (a number of which came to light following his death in 1981)—but what he did write continues to reverberate with readers today. Indeed, I would name his 1951 essay Chicago: City on the Make as being, with the possible exception of Mike Royko’s Boss, the best piece of writing about the city ever produced.

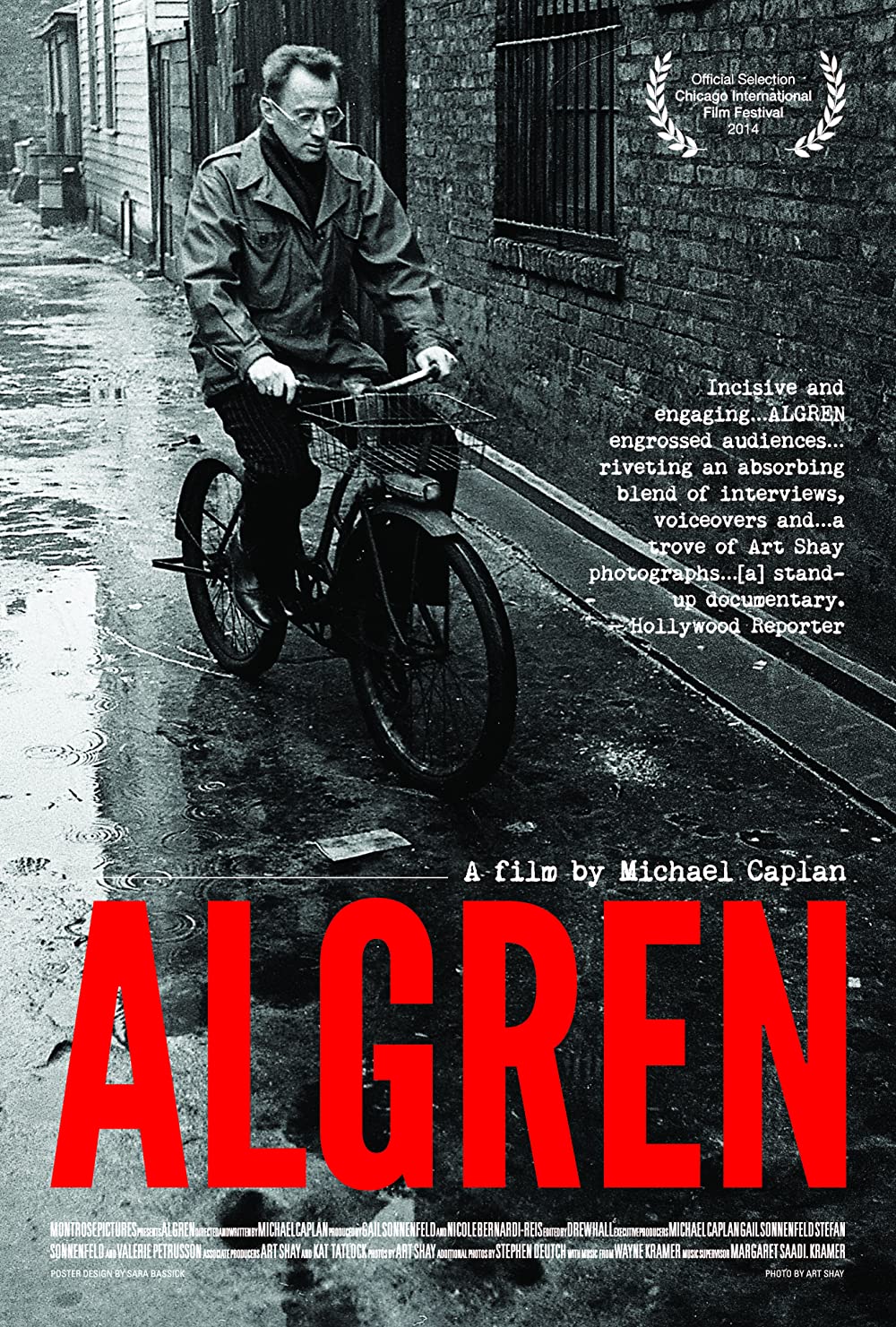

Alas, Algren’s literary reputation has faded somewhat in recent years. He is probably best known to most people, at least outside of Chicago, as the author of The Man with the Golden Arm, his harrowing 1949 novel about heroin addiction that was adapted into a 1955 film starring Frank Sinatra that, although strong for its day, he hated for what he felt was the bowdlerization of his work. (He also did not get along with director Otto Preminger, whom he felt had contempt for the characters instead of the sympathy he tried to demonstrate, and eventually filed a soon-withdrawn lawsuit against him after claiming ownership of his story with his “An Otto Preminger Film” credit.) Now comes “Algren,” a new documentary from Michael Caplan that hopes to resurrect his legacy for a new generation and to remind older readers of the still-considerable impact of his work.

As the film shows, Algren’s life was singular enough to inspire a book of its own. Although his writings might suggest a hardscrabble upbringing, he grew up on the city’s South Side in a middle-class neighborhood, graduated from the University of Illinois in 1931, and planned on a career in journalism. Alas, no one was hiring and after bumming around, he was busted in Texas for stealing a typewriter and spent several months in jail, a stay that allowed him to better understand and identify with those considered to be lower-class—bums, immigrants, junkies, criminals and other outsiders from polite society—that would become the focus of his writing when he returned to Chicago.

After publishing some award-winning short stories and the 1935 debut novel Somebody in Boots, he first courted controversy when his second novel, 1942’s Never Come Morning, so outraged Chicago’s large Polish-American community that Mayor Edward Joseph Kelly had the book banned from the Chicago Public Library. (In 1981, following his death, famed columnist Mike Royko convinced the city to name a street after Algren but the response from the Polish community was still so virulent that it was soon rescinded.) After serving in WWII, he returned to the city, published the short story collection The Neon Wilderness (1947) and began a romance with, of all people, French intellectual and feminist Simone de Beauvoir (who was still at the time with Jean-Paul Sartre) that would last for several years, end badly, and later be immortalized in de Beauvoir’s 1954 novel The Mandarins. (As the film reveals, he was then hired to review the book and, shockingly, it turned out that he was somewhat cool towards it.)

Then came the major success of The Man with the Golden Arm, which became a best-seller and won the first National Book Award. He would have one more success with the 1956 novel Walk on the Wild Side—which would also be turned into a movie he hated—but after that, there were no more novels and he found himself doing everything from teaching creative writing at the University of Iowa to going to South Vietnam to cover the war to working on a piece on the trial of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. The problem wasn’t his work as much as the fact that the times had changed. He specialized in writing about people who were barely clinging to the lowest rungs of the socio-economic ladder and that no longer appealed to the reading public.

Caplan illustrates his story via plenty of archival footage, interviews with a number of friends, fans and fellow authors, including William Friedkin, Russell Banks, Phillip Kaufman (who cast him in a small role in one of his early directorial efforts, the superhero spoof “Fearless Frank” [1967]) and—somewhat inexplicably—Billy Corgan. Best of all, there are long-unheard audio recordings of Algren, as well as a look at some of the elaborate photo collages that he created over the years. If nothing else, this film, along with the recent release “Live at Mister Kelly’s,” makes a good case for Chicago as arguably the cultural center of the world during this particular period in time.

“Algren” will serve well as an introduction to the man and his legacy to newcomers. If there’s a flaw to it, it’s that it pretty much follows the standard retrospective documentary template instead of doing anything unexpected or groundbreaking along the lines of what Algren did with his prose. However, the film’s real goal, when all is said and done, is to inspire new readers to pick up some of Algren’s work for the first time and discover what they’ve been missing. If that happens, “Algren” will have more than served its purpose.