Now into his seventy-ninth year, the German filmmaker Wim Wenders is on a bit of a hot streak. His warm, meditative “Perfect Days,” set in Tokyo and chronicling the late-life times of a sanitation worker in that city, is his best fictional narrative feature in what seems like a dog’s age. In the States at least, its release is preceded by one of Wenders’ always-unusual documentaries (indeed, in the past two decades or so, he has seemed to be more reliably productive in this mode than in the other). Its subject is the formidable and arguably forgiving artist Anselm Kiefer. Kiefer works in a variety of modes in works that address the catastrophic twentieth century suffered, and imposed on the rest of the world, by his home country.

Kiefer was born in 1945, a few months before Germany fell in World War II. His home city, Donauschingen, was heavily bombed in the war. Something of a child art prodigy, he nevertheless began his career in a conceptual mode rather than a figurative one. His early project “Heroic Figures” is a series of photographs depicting the artist posing in a “Seig Heil” salute at various sites through his land.

This sort of thing raised eyebrows, of course. Kiefer later created large-scale work addressing the metaphysics of fascism and war, using organic materials like straw and hair on his huge canvasses and then burning them. He applies a similar technique to his handmade books, each page as heavy as a brick or two. His guiding texts are often the poems of Holocaust survivor Paul Celan. The poet’s complex, sometimes seemingly hermetic lines are suffused with quiet, despairing grief. It would take a rather dense person to interpret Kiefer’s work as in any way pro-Nazi, or nostalgic for fascism. But there are plenty of dense persons in the world, and Kiefer, a complicated personality in himself (you won’t leave this portrait particularly impressed by the man’s modesty), responds to attempts at condemnation in a way that can seem, well, elliptical is one word.

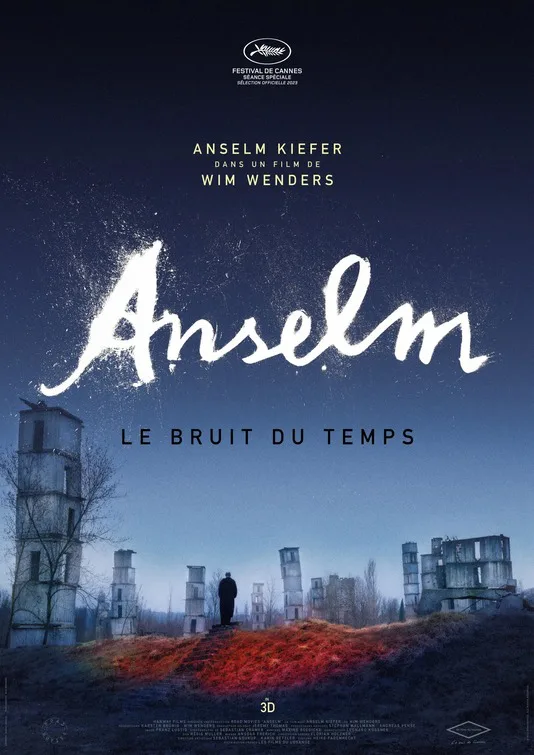

How does Wenders portray this intimidating figure? In 3D, for one thing. The director has been exploring this shooting format with, generally speaking, exemplary perspicacity over the years, in documentaries (the galvanic dance film “Pina,” about choreographer Pina Bausch) and at least one fiction film (the peculiar “The Beautiful Days of Aranjuez,” an adaptation of a stage work by his “Wings of Desire” co-scenarist Peter Handke). The format provides a welcome illusion of tactility when depicting Kiefer’s installation art, which is often outdoors in a powerful mix of almost conventional sculpture and earthworks. The artist bicycles around cavernous studios casually, dwarfed by stark dark visions. Franz Lustig’s 3D camera is unusually mobile, giving the viewer a sense of floating before the work. In fictionalized scenes, younger versions of Kiefer (played, in his twenties, by Daniel Kiefer, the artist’s son, and as a boy by Anton Wenders, the auteur’s great-nephew) stand or sit in wide-shot landscapes, taking things in.

These dramatizations underscore an important point, which is that Kiefer, being born when he did, grew up in an environment in which one was instructed to never talk about the past, even though one literally walked through its rubble every day, Kiefer’s mind, in a sense, was made up for him: he determined as an artist to not talk about anything else.

While there’s some archival footage used here, this is not a documentary that attempts to explain Kiefer by way of critical analysis or personal anecdote. The standard talking-head interview is not a feature here. But this doesn’t feel evasive. Wenders chooses to illuminate indirectly, and to compel the viewer to concoct questions of their own. The filmmaker’s decision to elide the issue of money is the only frustrating thing about the movie; one gets the impression that all the space and property depicted sprung full-blown from the artist’s skull, which is of course false. How the vision is supported is a legitimate point of curiosity, but as is sometimes typical of art world documentaries, “Anselm” seems to consider it too vulgar to even bring up.

In limited release today.