In his book The Films of My Life, the French director Francois Truffaut makes a curious statement. He used to believe, he says, that a successful film had to simultaneously express “an idea of the world and an idea of cinema.” But now, he writes: “I demand that a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema. I am not at all interested in anything in between; I am not interested in all those films that do not pulse.”

It may seem strange to begin a review of Francis Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” with those words, but consider them for a moment and they apply perfectly to this sprawling film. The critics who have rejected Coppola’s film mostly did so on Truffaut’s earlier grounds: They have arguments with the ideas about the world and the war in “Apocalypse Now,” or they disagree with the very idea of a film that cost $31 million to make and was then carted all over the world by a filmmaker still uncertain whether he has the right ending.

That “other” film on the screen — the one we debate because of its ideas, not its images — is the one that has caused so much controversy about “Apocalypse Now.” We have all read that Coppola took as his inspiration the Joseph Conrad novel Heart of Darkness, and that he turned Conrad’s journey up the Congo into a metaphor for another journey up a jungle river, into the heart of the Vietnam War. We’ve all read Coppola’s grandiose statements (the most memorable: “This isn’t a film about Vietnam. This film is Vietnam.”). We’ve heard that Marlon Brando was paid $1 million for his closing scenes, and that Coppola gambled his personal fortune to finish the film, and, heaven help us, we’ve even read a journal by the director’s wife in which she discloses her husband’s ravings and infidelities.

But all such considerations are far from the reasons why “Apocalypse Now” is a good and important film — a masterpiece, I believe. Years and years from now, when Coppola’s budget and his problems have long been forgotten, “Apocalypse” will still stand, I think, as a grand and grave and insanely inspired gesture of filmmaking — of moments that are operatic in their style and scope, and of other moments so silent we can almost hear the director thinking to himself.

I should at this moment make a confession: I am not particularly interested in the “ideas” in Coppola’s film. Critics of “Apocalypse” have said that Coppola was foolish to translate Heart of Darkness, that Conrad’s vision had nothing to do with Vietnam, and that Coppola was simply borrowing Conrad’s cultural respectability to give a gloss to his own disorganized ideas. The same objection was made to the hiring of Brando: Coppola was hoping, according to this version, that the presence of Brando as an icon would distract us from the emptiness of what he’s given to say.

Such criticisms are made by people who indeed are plumbing “Apocalypse Now” for its ideas, and who are as misguided as the veteran Vietnam correspondents who breathlessly reported, some months ago, that “The Deer Hunter” was not “accurate.” What idea or philosophy could we expect to find in “Apocalypse Now” — and what good would it really do, at this point after the Vietnam tragedy, if Brando’s closing speeches did have the “answers”? Like all great works of art about war, “Apocalypse Now” essentially contains only one idea or message, the not-especially-enlightening observation that war is hell. We do not go to see Coppola’s movie for that insight — something Coppola, but not some of his critics, knows well.

Coppola also well knows (and demonstrated in “The Godfather” films) that movies aren’t especially good at dealing with abstract ideas — for those you’d be better off turning to the written word — but they are superb for presenting moods and feelings, the look of a battle, the expression on a face, the mood of a country. “Apocalypse Now” achieves greatness not by analyzing our “experience in Vietnam,” but by re-creating, in characters and images, something of that experience.

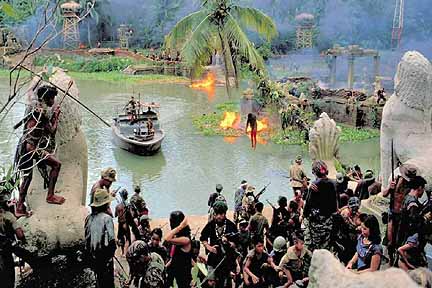

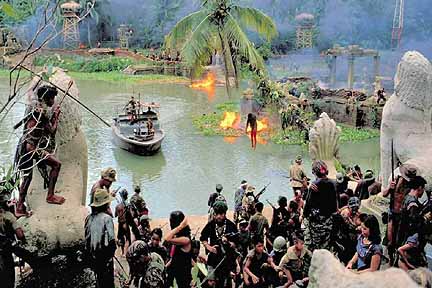

An example: The scene in which Robert Duvall, as a crazed lieutenant colonel, leads his troops in a helicopter assault on a village is, quite simply, the best movie battle scene ever filmed. It’s

simultaneously numbing, depressing, and exhilarating: As the rockets jar from the helicopters and spring through the air, we’re elated like kids for a half-second, until the reality of the consequences sinks in.

Another wrenching scene — in which the crew of Martin Sheen’s Navy patrol boat massacres the Vietnamese peasants in a small boat — happens with such sudden, fierce, senseless violence that it forces us to understand for the first time how such things could happen.

Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” is filled with moments like that, and the narrative device of the journey upriver is as convenient for him as it was for Conrad. That’s really why he uses it, and not because of

literary cross-references for graduate students to catalog. He takes

the journey, strings episodes along it, leads us at last to Brando’s

awesome, stinking hideaway … and then finds, so we’ve all heard, that he doesn’t have an ending. Well, Coppola doesn’t have an ending, if we or he expected the closing scenes to pull everything together and make sense of it. Nobody should have been surprised. “Apocalypse Now” doesn’t tell any kind of a conventional story, doesn’t have a thought-out message for us about Vietnam, has no answers, and thus needs no ending.

The way the film ends now, with Brando’s fuzzy, brooding monologues and the final violence, feels much more satisfactory than any conventional ending possibly could.

What’s great in the film, and what will make it live for many years

and speak to many audiences, is what Coppola achieves on the levels Truffaut was discussing: the moments of agony and joy in making cinema. Some of those moments come at the same time; remember again the helicopter assault and its unsettling juxtaposition of horror and exhilaration. Remember the weird beauty of the massed helicopters lifting over the trees in the long shot, and the insane power of Wagner’s music, played loudly during the attack, and you feel what Coppola was getting at: Those moments as common in life as art, when the whole huge grand mystery of the world, so terrible, so beautiful, seems to hang in the balance.