The path of an artist is never straightforward or easygoing. But the challenges are even greater for women who, as artists, create their work as a reflection of the way they see and move through the world.

Throughout the astonishing artifact of a movie “Apolonia, Apolonia”—the kind of film whose essence patiently and gradually materializes like an abstract painting in the making—Danish documentary filmmaker Lea Glob affirms this aforesaid hardship in countless, studious, and affectionate ways. Her intricate portrait of Apolonia Sokol, the on-the-rise French figurative painter whom Glob met in 2009 and filmed for 13 years, is full of such details. But Glob’s own presence in her doc makes an equally essential point about womanhood and artistry, by doubling down on the film’s multifaceted thesis. The result is something deeply reflective about femininity, culture, commerce, friendship, sexuality and the various souls who dwell in the impossible intersection of it all.

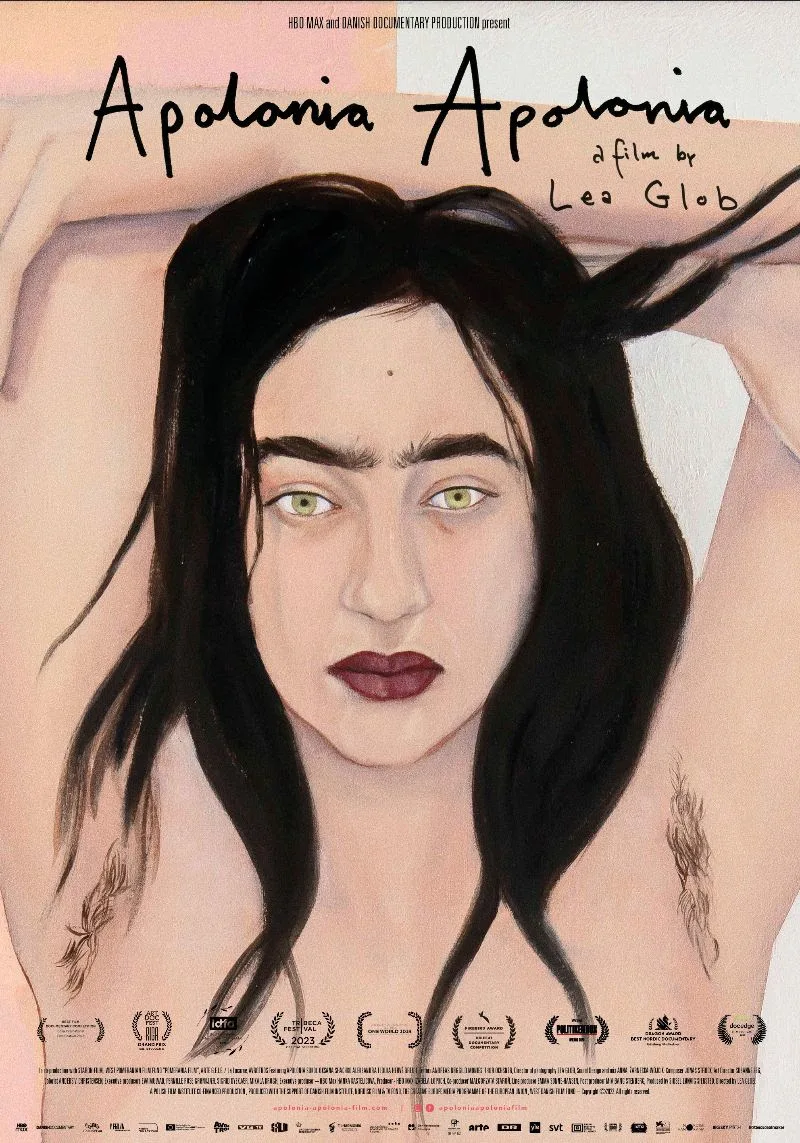

In that regard, Glob’s film is far from a cliched fly-on-the-wall cinematic portraiture, and the type of documentary that usually grabs the attention of the Oscars. (This one fortunately and miraculously did, as the movie is now a part of the Academy’s coveted shortlist of a handful of documentaries competing for the top prize in the non-fiction category.) It is instead an experimental work in which the subject and the filmmaker are pronouncedly enmeshed, one as edgy as its chief subject Apolonia, a tireless creator of angular features, typified by a resolute demeanor and bangs that she trims herself like a sculptor of her own image.

In the beginning, Apolonia seems to have all the good fortune and promise a painter could desire. Born into an artistic community in an underground theater in Paris, she studies at the prestigious art academy Beaux-Arts de Paris and leads an enviable bohemian life in one of the most beautiful cities of the world at the very theater she was raised in, now a communal hostel of sorts where Apolonia hosts up-and-comers like herself.

But as Glob returns to Apolonia time and time again, she observes that those assets that once made her a thriving and inspired artist are seemingly slipping right through her hands as Apolonia seeks and fights for a fulfilling and productive life on her own terms. As we watch the ups and downs of her life and restless artistic process, we do take note that many things that are hard for her to attain and maintain would likely come easy to her male counterparts, even if they aren’t as talented. In one scene, we watch Apolonia complain about her male professors in anger. When one of them insults Apolonia’s paintings by insinuating that they aren’t as interesting as she is, through voice over, Glob wonders if they would’ve said the same to a male painter. You can’t help but agree with both the director and subject’s irritation.

Still, Apolonia sticks with her chosen path, even when she loses her theater community and finds herself stuffed in a tiny apartment with her mom and her friend Oksana, a Ukrainian artist and unapologetically feminist activist seeking asylum. The beautiful relationship between the two women who pledge against marriage and children and all-things they deem patriarchal gradually becomes the film’s most heart-swelling (and at times, heartbreaking) core as the duo deal with their fair share of problems, with Oksana also struggling with her vulnerable mental health.

“Apolonia, Apolonia” is at its most engaging when the titular artist hops from city to city, country to country, and eventually finds herself in the US. New York City doesn’t work out for her, so Apolonia heads to sunny Los Angeles next, where she falls into the circle of vampiric collector and commercial enabler Stefan Simchowitz, known (per The New York Times) as “the patron Satan of the art world.” Here, Apolonia temporarily gets dizzied by the capitalistic possibilities offered at her, among them is a nice studio to call her own. But the impossible demands to mass-create more than double the work she’s used to in any given month eventually catch up with her. After all, she is an artist who soars when inspiration hits, not when commercial mandates suffocate and own her.

Eventually, Apolonia returns to what she calls “the old world,” trying to re-build an artistic trajectory of her own choosing. That’s when Glob’s loving camera also increasingly captures the filmmaker herself through a difficult pregnancy and its treacherous aftermath, finding in herself another woman artist grappling with newfound priorities men are seldom confronted with. The film resolves to a piercing parting note from there—not a clear-cut ending, but a quiet celebration of the perpetuity of women’s fighting spirits.