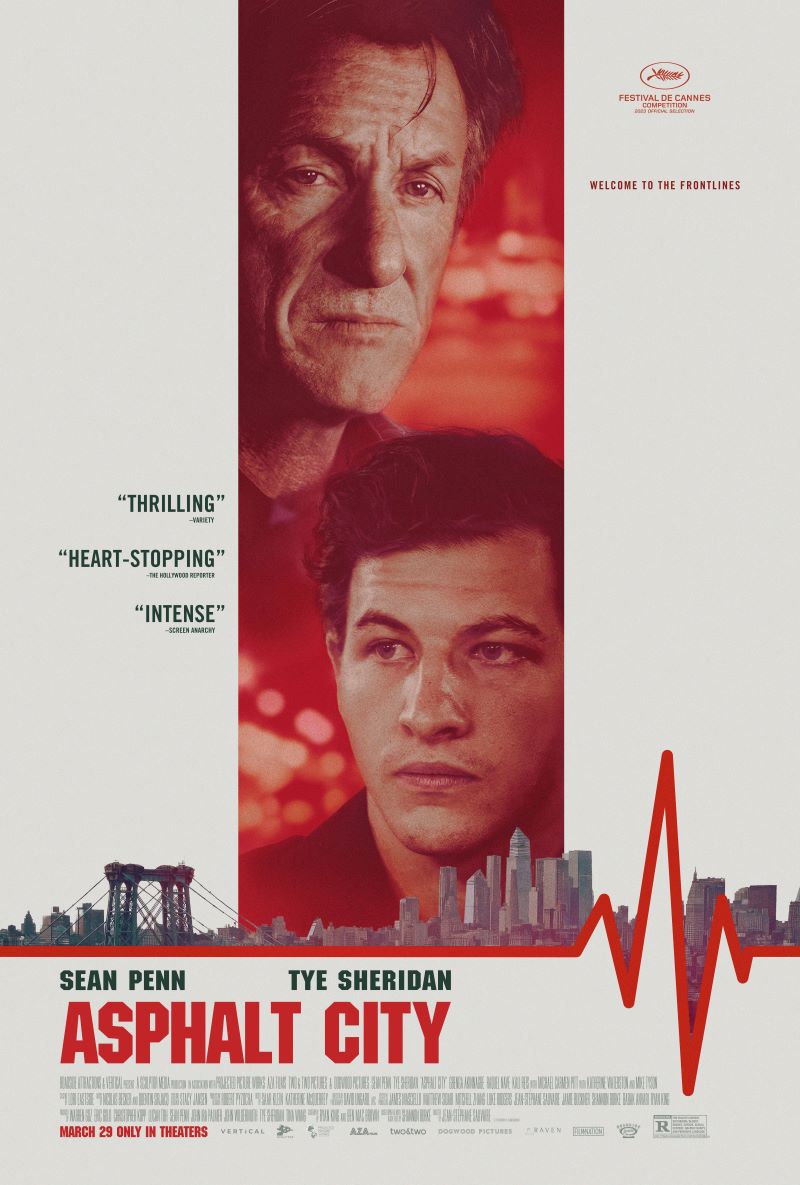

You may remember a scene in the cult classic “Repo Man” in which, during a high-speed auto repossession, Emilio Estevez exclaims, “This is intense,” and Harry Dean Stanton laconically replies, “Repo man’s always intense.” Same goes for being a big city paramedic, and you might not even need the movies to tell you that. “Asphalt City,” directed by Jean-Stephane Sauvaire from a script by Ryan King and Ben Mac Brown, adapting the 2008 novel Black Flies by Shannon Burke, begins in the middle of a particularly fraught outer-boroughs NYC emergency medical intervention, as hapless, new-to-the-department Ollie (a fresh-faced but still beleaguered looking Tye Sheridan) tries to treat a gunshot victim after a housing project shootout. Screenwriters King and Brown don’t overexert themselves concocting fresh-sounding dialogue; “I’m trying to do my f**king job here,” “fu**ing rookie” and even “I’m getting too old for this s**t” are heard on the busy, multi-channel soundtrack.

Director Sauvaire likes to chronicle extreme life situations, and his style of sound and vision overload served him reasonably well in the boxing-in-a-Thai-prison punchfest “A Prayer Before Dawn” in 2018. That movie had an unusual narrative that kept it unusually buoyant. The story here is more familiar.

You know the deal. You become a big-city paramedic to help people. But the people themselves are a nightmare! Not particularly into self-care, often living in squalor, they don’t speak the language, and they don’t even say thank you after you save their lives! It can get to be a real grind. Ollie doesn’t help his own existential outlook by rooming in Chinatown with a couple of ancients, in order to save money while he studies for med school. He’s also in an intense and arguably odd sexual relationship with a single mother with whom he doesn’t communicate effectively, to say the least.

A bigoted white male urbanite watching this movie might get a particular message—and it’s possible this isn’t intentional, but still—from its first half hour of emergency sequences. That message being, every ethnic group he finds frightening, he is correct in finding frightening. Hyped up Black kids with guns! Chunky shirtless Hispanic guys with gallons of ink on them messing around with pit bulls—the mean kind, not the ones they’re always telling you are safe for adoption! Heroin-addicted maybe-Filipino women spitting obscene invective for minutes on end in the back of an ambulance! It really IS a jungle out there! Holy moly!

If Sheridan’s Ollie has a hard time keeping his head above water, his good shift partner, the older, grizzled Rutovsky—Rut for short—seems to have things relatively figured out, at least at first. Played with commendable understatement by Sean Penn, Rut is not a total cynic after years on the force. He knows the moves, and has a pronounced sense of pragmatism, which leads him into very dark moral waters as the movie goes on. (Rut has an estranged partner played by Katherine Waterson, whose Expression of Disapproval shows her as a true chip off the old block, that is, her father Sam.) Michael Pitt, beefed up and puffy-faced and coming on like he wants to be in the next “Boondock Saints” movie, plays bad shift partner Lafontaine, and he has the worst lines in the movie: “I don’t know if I believe in Heaven but I believe in Hell,” hoo boy, and, in case you weren’t paying attention to that one, “I ain’t Jesus, I’ll tell you that.” On the other hand, Mike Tyson, as Ollie’s gruff station chief, is so credible that the phrase “stunt casting” barely has a chance to form in one’s head before completely dissipating.

Perhaps paradoxically, it’s when the film is at its most quiet that it’s also most persuasive. A dour scene in which Ollie and Rut go to a nursing home and find a neglected patient with his lungs filling with liquid, contemplating that the trip to the hospital will result in an immediate bounce back to the substandard care facility, understanding that they’re just enacting a pantomime, is uncomfortable and powerful. Also memorable is a scene in which Penn and Sheridan’s characters mordantly shoot the breeze while walking through a wintry, deserted Coney Island. But then you have the overstatement of the black flies in the apartment of a corpse (the film’s original title was that of the novel) or of a childbirth tableau so blood-soaked it makes the finale of “Immaculate” look tasteful. Sometimes maximum intensity doesn’t yield optimal results.