“Never give in to hope.” Lucy (Jennifer Connelly) writes these words on the white board while attending a “semi-silent retreat”. The retreat’s atmosphere is tense, and Lucy is uptight and irritated, all of which defeats the whole purpose of a retreat. Judging from the motivational tapes she listens to in the car, and the fact she has attended this thing at all, Lucy is steeped in this self-help world. From the looks of it, it doesn’t seem to be helping. “Never give in to hope” is a pretty bleak statement, but we find out later she’s actually quoting the guru at this event, a smiling weird sage named Elon Bello (Ben Whishaw). Maybe Lucy is trying to imagine herself into Elon’s charmed circle of blissed-out enlightenment. Maybe she’s skeptical. Maybe she wants to be picked as Elon’s favorite and quotes him to get brownie points. It’s hard to tell.

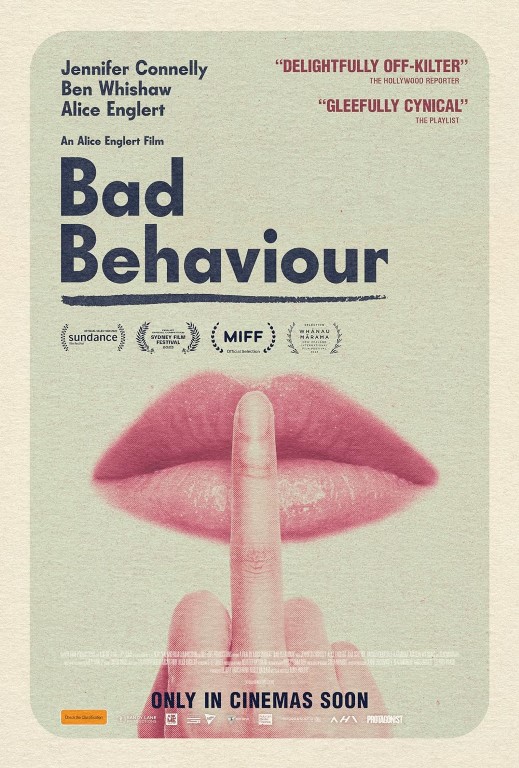

It’s hard to tell about a lot of things in Alice Englert’s “Bad Behaviour”. The script, also by Englert, is ambitious in its exploration of the fraught ties between a mother and daughter, the two women so similar and yet separated by distrust and old wounds. The story is split between Lucy at the retreat and Lucy’s daughter Dylan (Englert, again), on location in New Zealand, working as a stuntwoman. This is meant to be a bifurcated tale, but Lucy’s journey is so much more compelling than Dylan’s, who mainly seems to be a giggly playful person, crushing on a fellow stunt guy, and avoiding her mother’s phone calls. Every time the film cuts away to a Dylan section, everything deflates. Dylan does eventually rise in importance in the second half of the film, but by then it’s too late.

Lucy’s journey is the real guts of “Bad Behaviour” and Connelly gives her best performance in years, mainly because Lucy is the best role she’s had in years. Lucy is all prickly defenses, all corners and angles. The other people at the retreat clock her immediately as not “one of them”. Three younger women interrogate her, and their dead eyes looking at her tell Lucy they have no interest in getting to know her, and they definitely don’t respect her as an “elder”. Her life experience means nothing to them. Lucy is a demanding role, and Connelly at times looks ravaged by the emotions tearing her up from the inside. Connelly outdoes herself.

Dasha Nekrasova plays the narcissistic Beverly, lazily self-satisfied, saying what Elon wants to hear, and looking on at other people with bored indifference. Dasha very quickly becomes Elon’s “favorite”: he laughs with pleasure when he sees her and tells the other participants to just follow Beverly’s lead. She is enlightened already; she can show them. Lucy is triggered by Beverly in a really outsized way. She can’t get a grip. She starts to deteriorate. Once the deterioration begins, it can’t be stopped.

How can Dylan giggling and flouncing around, somersaulting down the hallway, scrolling on her phone, compete with the Lucy’s breakdown? She can’t. The mother-daughter relationship is supposed to be central, at least the idea of it, but by the time Lucy and Dylan are brought back together, it’s hard to connect the dots. Something doesn’t add up. Every scene involving Lucy reveals a little bit more, while every scene involving Dylan just sits there onscreen, a flat wall revealing nothing.

“Bad Behaviour” is a frustrating watch. Englert doesn’t wrestle the material into a manageable form, and struggles to find a consistent tone. The retreat is rich ground for mockery. In fact, the retreat begs to be mocked (perhaps not to the level of “Semi-Tough,” but close). The guru’s name is Elon, for God’s sake. It’s a “semi-silent retreat”. The retreat can’t even commit fully to silence! This is very funny, but nothing is made of it. Maybe the humor is unintentional. Beyond a couple glimpses of Elon not practicing what he preaches, the retreat and the desires behind such ventures aren’t interrogated. There isn’t a real point of view in operation. This gives the film a muffled inert feeling.

The only game in town here is Connelly’s masterful portrayal of a woman in the process of disintegrating, going beyond the pale of every norm there is, throwing off the restraints of a lifetime. It’s nice to see Connelly playing a prickly unfriendly woman, defensive but very intelligent. Her eyes are sharp. She doesn’t look at people. She sizes them up. Her performance is fascinating, and it deserves a better, more focused movie.