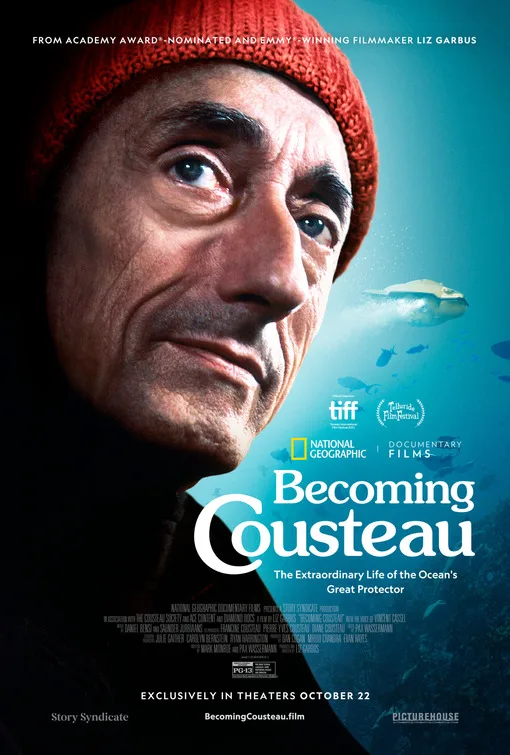

“Diving is the most fabulous distraction you can experience,” Jacques Cousteau once said. And as the early moments of Liz Garbus’ intimate and deeply informative documentary “Becoming Cousteau” remind the audience, the pioneer was always in his most comfortable state underwater—so much that he once defined the misery of emerging from the blue depths as being forced back to earth after being introduced to heaven.

These thoughts are not surprising for a man whose name has been synonymous with all things aquatic as an innovator, explorer, conservationist, and filmmaker who wanted to be the John Ford or John Huston of the ocean. Resourcefully using grainy archival footage and audio files—as well as segments from Cousteau’s diaries, read in voiceover by Vincent Cassel—Garbus dives deep into all these aforesaid facets of Cousteau’s work and tireless efforts, while expertly weaving them with the lesser known and not entirely pleasant aspects of his private life as a father and husband. The result is a captivating, sincere, and articulate documentary about a household name that will satisfy and even enlighten those of us who grew up with the man’s mesmerizing TV series, “The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau,” as well as introduce a new generation of young, aspiring explorers and conservationists to his legacy. While it on the whole doesn’t feel as engrossing as some of the filmmaker’s former, more innovative movies (the terrific “What Happened, Miss Simone?” comes to mind), “Becoming Cousteau” is still as immersive and warmly inviting as non-fiction biographies come.

Smartly, Garbus keeps her narrative’s chronology straightforward and starts Cousteau’s tale from his young days when he wanted nothing more than to become a pilot. But a major car crash changed the course of his life in his mid-20s, when he started rehabilitative swimming to heal his injuries and grew an insatiable curiosity towards diving. It was during this time that he had to invent and innovate, with his constraints driving his original thinking to overcome them. Enter waterproof cameras and the revolutionary breathing device, Aqualung, without which the contemporary open-water diving wouldn’t be where it is today. Also came Calypso along with its handsome crew in the early 1950s, the research-focused excursion boat, immortalized through the captain’s groundbreaking visual output on TV and in movies, before such breathtaking expeditions were commonly accessed by average human beings from their living rooms on channels like National Geographic and Discovery.

Garbus’ greatest feat in “Becoming Cousteau” is the clarity with which she maps out the trajectory of Cousteau’s change of heart around issues concerning the environment. He and his squad were by and large irresponsible for quite a while in how they interacted with and manipulated the ocean’s precious ecological balance. In that regard, there are scenes in her doc that show Team Cousteau unflatteringly—blowing up fish, locating oil sites for money, tantalizing tortoises, and even proudly killing a poor shark fighting for dear life. (This last instance is in fact in Cousteau’s Oscar-winning 1956 documentary, “The Silent World,” a scene the captain himself couldn’t stand behind or even watch in his later, ecologically conscious years.) But all that became history for Cousteau in the ‘60s when he stepped up as one of the world’s first celebrities to speak about climate change. This groundbreaking conversion meant shifting gears sharply in his films and overall work to assume an activism-oriented, educational focus.

It’s through these developments that Garbus’ film earns an increasingly urgent tone without being preachy or giving up its charming vintage feel, organically instilling in the viewer a willingness to reconsider their own environmentally unfriendly habits. Elsewhere, Garbus thankfully doesn’t hide Cousteau’s shortcomings, portraying an imperfect, chaotic, and work-centric hero who didn’t devote enough time or care to his family—his wife Simone (who was instrumental in operating his ship) and his two sons, Philippe and Jean-Michel. The film dedicates a good portion of its running time to Philippe, who was hands-on committed to his dad’s work until his tragic passing in a plane crash at the young age of 38. Later in 1990, Cousteau lost his wife Simone to cancer, and married Francine Triplet shortly after. (At that point, he already had two kids with Francine.)

It’s thanks to this full-fledged honesty that “Becoming Cousteau” rises above the trappings of a simple-minded nostalgia trip. As curious-minded as its immortal subject, Garbus’ film has a refreshingly forward-looking perspective, delivering a hopeful plea towards a future that’s worth saving.

Now playing in theaters.