Bill Cobbs walks into a fictional inn in fictional Llanview, Pennsylvania. He’s playing a building inspector on an undistinguished episode of the undistinguished soap opera “One Life To Live.” The show has several guest stars in that episode, including Jason Alexander and Eriq La Salle, both looking impossibly young. Not Cobbs. Cobbs was never a young man on film. His first credited appearance is in Joseph Sargent’s classic crime film “The Taking of Pelham 123,” but he’s background texture, on somebody’s roster as a dependable New York theater actor, which was what he was in the early ’70s. He was 38 years old.

By the time he was getting speaking parts of note, he looked like he would when my generation heard him utter the immortal words: “This dog is a registered member of the team as well as a mascot. He practices with the team, travels with the team, and plays with the team. Bet you won’t find anything that says a dog can’t play.” In the episode of “One Life to Live,” he walks up to the owner of an inn and makes it clear he’ll be dealt with. “Now, what’ll it be? The hard way… or my way?” His hard expression softens, and a smile emerges. It’s like you forgot a minute ago that he’s playing the episode’s villain. A minute of screen time on an episode of television designed to be forgotten, and Bill Cobbs made it real.

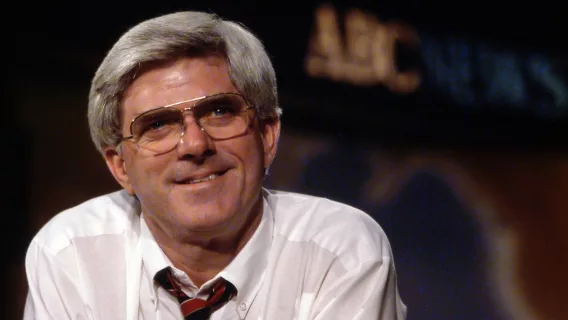

Willbert Francisco Cobbs had a face (and especially a voice) you only ever needed to hear once for him to become immortalized in your memory. The phrase “Hangdog expression” might as well have been invented to describe the lowkey actor with the megawatt charisma. Maybe you first encountered him in your favorite movie as a kid; maybe it was in a blockbuster he’d saunter off with when plausibility couldn’t otherwise find purchase. Whatever the case, it only takes one viewing to memorize Bill Cobbs.

Cobbs came to acting late in life. He was born in Cleveland to working-class parents, and he himself may have just been working class, too. He spent almost a decade in the Air Force before returning to civilian life without a direction. That is until he met Reuben Silver, a Cleveland theatre luminary who had been in the Yiddish theater in Detroit from the time he was a boy. Silver took a gig as the head of the Karamu House theater, where he brought the works of Samuel Beckett and Edward Albee to Cleveland and was instrumental in giving parts to Black actors like Cobbs, who was so moved by Silver’s support he spoke at his funeral in 2014. The bug firmly caught, Cobbs moved to a bigger pond, specifically Manhattan, where he joined the Negro Ensemble Company, co-founded by Douglas Turner Ward, whose work was staged at the Karamu House back in Cleveland. Cobbs evidently electrified in Ossie Davis’ “Purlie Victorious.”

Ward, like Reuben, was the kind of figure you couldn’t help but want to follow. He’d criticized the whiteness of the American theatre in the pages of the New York Times, and when he founded the N.E.C., he attracted some of the best talent the stage and screen has ever known. Moses Gunn, Keith David, Danny Glover, Glynn Turman, S. Epatha Merkerson, Richard Roundtree, Clevon Little, Samuel L. Jackson, Delroy Lindo, and fellow “One Life to Live” guest star Laurence Fishburne all strode through the company at one time or another. What did it say to the world that the relatively unproven Bill Cobbs was soon headlining plays under Ward’s direction among this esteemed company?

He never fell out of love with the theater, even as he turned to work much more consistently in film and television. He worked with Ward into the 80s, understudied for Joe Seneca during the original Broadway run of August Wilson’s “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” and performed in a celebrated stage production of “Driving Miss Daisy” in Chicago just as the movie with Morgan Freeman was being produced. His credits on stage dropped off after this, but his love for it and his hardworking parents instilled in him the kind of ethic that allowed him to take, without pretension, whatever parts were given to him. It was work, and nobody worked harder while making it look easier.

For a while, he was like the low-budget circuit’s best-kept secret. He took supporting parts in “Cooley High” Michael Schultz’ “Greased Lightning” alongside Richard Pryor and Pam Grier, “A Hero An’t Nothin but a Sandwich“ with Paul Winfield, and the completely forgotten “The Hitter” or “Don’t Call Me Boy,” a blaxploitation riff on Walter Hill’s “Hard Times” and Robert Rossen’s “The Hustler.” Cobbs plays a Minnesota Fats-type figure (hilariously called Louisiana Slim), a pool shark and pimp who Ron O’Neal goes out of his way to humiliate. Cobbs may be a criminal scoundrel, but he has style, and you can’t take your eyes off him.

He’d get another stab at the milieu when he appears for a few memorable moments in Martin Scorsese’s “The Color of Money,” the sequel to “The Hustler.” In that, he’s a guy who tells stories with a gaze. Paul Newman looks him in the eye, and Cobbs returns a stare that says, “Your golden boy blew it, and your night’s about to get worse.” Cobbs was great at playing guys posted up in front of or behind bars. You bought that he’d been shellacked in place in any given watering hole. In “Trading Places,” the short-lived Dabney Coleman show “The Slap Maxwell Story” and John Sayles’ marvelous “The Brother from Another Planet,” he’s the guy in the bar with the stories, the man you can always talk to. “Youngbloods got no sense of history comin’ up…” he says, world-wearily. Cobbs would frequently gift the most memorable lines in a movie. And even if he wasn’t, he found ways to stand out.

He graced several personal epics by great American directors, like Claudia Weill’s “Johnny Bull,” Clint Eastwood’s “Bird” and Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Cotton Club,” both based on true events, and terrific B movies with A ambitions like Mario Van Peebles’ “New Jack City” and Wes Craven’s delirious “The People Under The Stairs” where a “sense of history” is just what he imparts, scaring a little sense (but not enough) his grandchildren robbing from white suburbanites in the latter and providing drug dealer Wesley Snipes with his reckoning in the former. If the young bloods had only listened to him… certainly everyone in the audience was.

He tells the story of gentrification as a ghost story in “Stairs,” and it’s mesmerizing, the perfect use of an actor’s gravitas and baggage. By now, everyone knew the kind of character Cobbs played, and when he showed up, the sheen of respectability, of experience, made him practically glow. That’s why when Gregory Hines got his own TV show (as charming as sitcoms ever get), there was only one choice for the man to play his father. That’s why the Coen Brothers entrusted him with the unenviable task of playing a magic clock tender in their whacky but soulful “The Hudsucker Proxy.” It’s not their most progressive piece of writing, and an actor with less certainty and dignity may have had trouble imbuing the character, a pretty classic example of the magical negro trope, with any reality. The film is underrated for a million reasons, and Cobb’s performance is right at the top of the list.

Cobb’s presence could help sell narratives of historical trauma because he could so easily project internal conflict. That he’d been hiding something, swallowing years of injustice, now worn as a perpetual scowl. In movies like “Carolina Skeletons,” “Ghosts of Mississippi,” and the incredible “Nightjohn,” he’s a man who’s seen it all. “Nightjohn” is the best of the pack by a wide margin, directed by the great Charles Burnett and based on a book by Gary Paulsen. In it, he’s the elder field hand on a slave plantation, and there’s nothing he can’t predict when it comes to how everyone will be treated. His performance is all business, and the best character beat is when he, against his better judgment, plays drunk with paddy rollers so a younger man can get by them married in the dead of night.

Cobbs’ body of work, like any jobbing character actor, was full of peaks and valleys, but he made Nightjohn and appeared in Michael Apted’s “Always Outnumbered,” starring fellow N.E.C. alum Laurence Fishburne, written by Walter Mosley. Those are two of the best films made in my lifetime, and two of the best films about race somehow made in a system driven by the white impulse to conceal history.

A few months back, the writer David Moses observed that all Black cinema counts as what I would call The Unloved because the people judging and paying for it and ensuring it got its meager day in the sun were white. Thus, there was an element of condescension through access. The white producers and critical classes deigned to allow Black directors and writers their day in the sun because there was no alternative for years of mass producing and distributing Black cinema but through white channels. Cobbs was at once part of hijacking the accepted narratives and a reminder of what black actors were allowed to do in Hollywood. Jerrod Carmichael knew it when he cast him on an episode of “The Carmichael Show.”

Cobbs’ first role in a real blockbuster was as Whitney Houston’s trusted manager in “The Bodyguard,” a movie that would have no virtues if this cast weren’t involved. Cobbs stands tall above the overqualified cast, which also includes Kevin Costner, Mike Starr, and Richard Schiff. Casting directors are creatures of habit, and so Cobbs became the go-to for the face of strained tolerance in movies for white audiences with white casts. “Air Bud” is the most famous of these films, in which he swaggers like James Brown into the film to deliver his immortal line about a dog’s right to play basketball. It became a meme long before the term was coined, which is its own reward, but the list of mediocrities he elevated is nearly endless.

The movies about animals alone are vast: “Paulie,” “Ed,” “Night at the Museum,” “Duck,” and “The Derby Stallion.” There’s a beautiful joke about this phenomenon of having Cobbs around to legitimize artifacts of the white entertainment industry in Christopher Guest’s “A Mighty Wind,” about a folk revival. Cobbs appears for maybe ten seconds as a blues musician who wishes he was anywhere but an industry party for folkies (a part he played without the quotation marks in Tom Hanks’ “That Thing You Do!”). Michael McKean talks to him as if he cares one scintilla about the fortunes of new folk music. His replies barely qualify as words, and the misery he’s trying his best to hide is priceless. It’s the thing about that movie I’ve never stopped thinking about since it premiered in 2003.

As Cobbs grew ever more popular, the quality of the movies decreased, and the TV veered from great (“The Sopranos”) to the surreally forgettable (“Superior Donuts,” “Harry’s Law”). He made a few more good movies like the charmingly low-key “Get Low” and the “Nashville” riff “Sunshine State,” once more for John Sayles, in which he’s very winning as a firebrand activist. Sam Raimi, uncredited co-director of “The Hudsucker Proxy,” had him essentially reprise his role there for “Oz The Great and Powerful,” and he was one of a million stars in the 2011 “Muppets” reboot.

As of this writing, he’s got five more things still coming out, which is as much a window into his productivity late in life as anything. He died at age 90, leaving behind 200 screen credits, many un-captured stage performances, and the most memorable presence an actor could hope to have without ever betraying his talent or taking for granted what a strange turn of events led a 36-year-old car salesman to decide to become one of the most welcome and beloved screen actors of his generation. There’s never a moment where you see Bill Cobbs and aren’t immediately grateful. Bill Cobbs did things the hard way, his way. And American cinema was never the same.