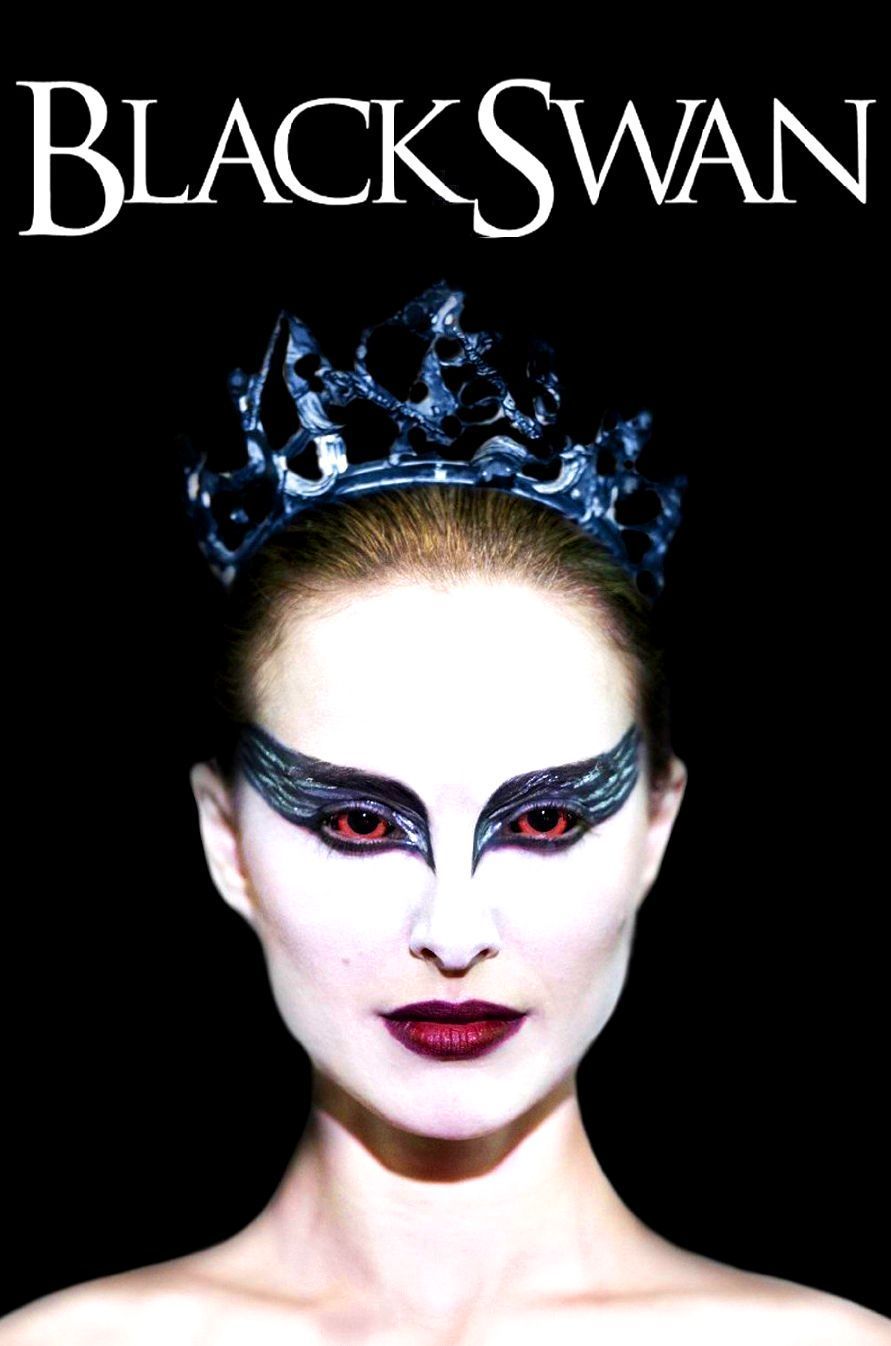

Darren Aronofsky’s “Black Swan” is a full-bore melodrama, told with passionate intensity, gloriously and darkly absurd. It centers on a performance by Natalie Portman that is nothing short of heroic, and mirrors the conflict of good and evil in Tchaikovsky’s ballet “Swan Lake.” It is one thing to lose yourself in your art. Portman’s ballerina loses her mind.

Everything about classical ballet lends itself to excess. The art form is one of grand gesture, of the illusion of triumph over reality and even the force of gravity. Yet it demands from its performers years of rigorous perfectionism, the kind of physical and mental training that takes ascendancy over normal life. This conflict between the ideal and the reality is consuming Nina Sayers, Portman’s character.

Her life has been devoted to ballet. Was that entirely her choice? Her mother, Erica (Barbara Hershey), was a dancer once, and now dedicates her life to her daughter’s career. They share a small apartment that feels sometimes like a refuge, sometimes like a cell. They hug and chatter like sisters. Something feels wrong.

Nina dances in a company at New York’s Lincoln Center, ruled by the autocratic Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel). The reach of his ego is suggested by his current season, which will “reimage” the classics.

Having cast off his former prima ballerina and lover, Beth MacIntyre (Winona Ryder), he is now auditioning for a new lead. “Swan Lake” requires the lead to play opposite roles. Nina is clearly the best dancer for the White Swan. But Thomas finds her too “perfect” for the Black Swan. She dances with technique, not feeling.

The film seems to be unfolding along lines that can be anticipated: There’s tension between Nina and Thomas, and then Lily (Mila Kunis), a new dancer, arrives from the West Coast. She is all Nina is not: bold, loose, confident. She fascinates Nina, not only as a rival but even as a role model. Lily is, among other things, a clearly sexual being, and we suspect Nina may never have been on a date, let alone slept with a man. For her, Lily presents a professional challenge and a personal rebuke.

Thomas, the beast, is well known for having affairs with his dancers. Played with intimidating arrogance by Cassel, he clearly has plans for the virginal Nina. This creates a crisis in her mind: How can she free herself from the technical perfection and sexual repression enforced by her mother, while remaining loyal to their incestuous psychological relationship?

No backstage ballet story can be seen without “The Red Shoes” (1948) coming into mind. If you’ve never seen it of course eventually you will. In the character of Thomas, Aronofsky and Cassel evoke Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook), the impresario in that film, whose autocratic manner masks a deep possessiveness. And in Nina, there is a version of Moira Shearer’s ingenue, so driven to please.

“Black Swan” will remind some viewers of Aronofsky’s previous film, “The Wrestler.” Both show singleminded professionalism in the pursuit of a career, leading to the destruction of personal lives. I was reminded also of Aronofsky’s brilliant debut with “Pi” (1998), about a man driven mad by his quest for the universal mathematical language. For that matter, his “The Fountain” (2007) was about a man who seems to conquer time and space. Aronofsky’s characters make no little plans.

The main story supports of “Black Swan” are traditional: backstage rivalry, artistic jealousy, a great work of art mirrored in the lives of those performing it. Aronofsky drifts eerily from those reliable guidelines into the mind of Nina. She begins to confuse boundaries. The film opens with a dream, and it becomes clear that her dream life is contiguous with her waking one. Aronofsky and Portman follow this fearlessly where it takes them.

Portman’s performance is a revelation from this actress who was a 13-year-old charmer in “Beautiful Girls” (1996). She has never played a character this obsessed before, and never faced a greater physical challenge (she prepared by training for 10 months). Somehow she goes over the top and yet stays in character: Even at the extremes, you don’t catch her acting. The other actors are like dance partners holding her aloft. Barbara Hershey provides a perfectly calibrated performance as a mother whose love is real, whose shortcomings are not signaled, whose own perfectionism has all been focused on the creation of her daughter.

The tragedy of Nina, and of many young performers and athletes, is that perfection in one area of life has led to sacrifices in many of the others. At a young age, everything becomes focused on pleasing someone (a parent, a coach, a partner), and somehow it gets wired in that the person can never be pleased. One becomes perfect in every area except for life itself.

It’s traditional in many ballet-based dramas for a summing-up to take place in a bravura third act. “Black Swan” has a beauty. All of the themes of the music and life, all of the parallels of story and ballet, all of the confusion of reality and dream come together in a grand exhilaration of towering passion. There is really only one place this can take us, and it does. If I were you, I wouldn’t spend too much time trying to figure out exactly what happens in practical terms. Lots of people had doubts about the end of “The Red Shoes,” too. They were wrong, but they did.