The screenplay for “Blood Brother” establishes an intriguing premise, filled with broken alliances, conflicted allegiances, and a dark secret from the past that could either bring together a group of old friends or destroy whatever remains of their bond. Then, one of those old friends definitively shows that he’s a madman, bent on bloody and violent revenge, and the movie’s promise collapses under the weight of inconsistent characters and a generic, cliché-ridden plot.

Its central story revolves around four friends who grew up together in an impoverished section of an unnamed city. The movie, by the way, clearly was shot in New Orleans, but to actually name the place would mean the filmmakers had the location planned before filming and/or actually cared about the specifics of their story.

When they were teenagers, the friends routinely got into trouble, with crimes as petty as vandalism (spray-painting their gang name the “Demons” on walls) and as serious as armed robbery. The defining moment of their youth and their shared future was a chance encounter with the attempted robbery of an armored truck. With the robbers and all but one of the guards dead, the teens stole $3 million, and the most violent of the quartet killed the only surviving witness. He was arrested and sent to prison. The other three went on with their lives.

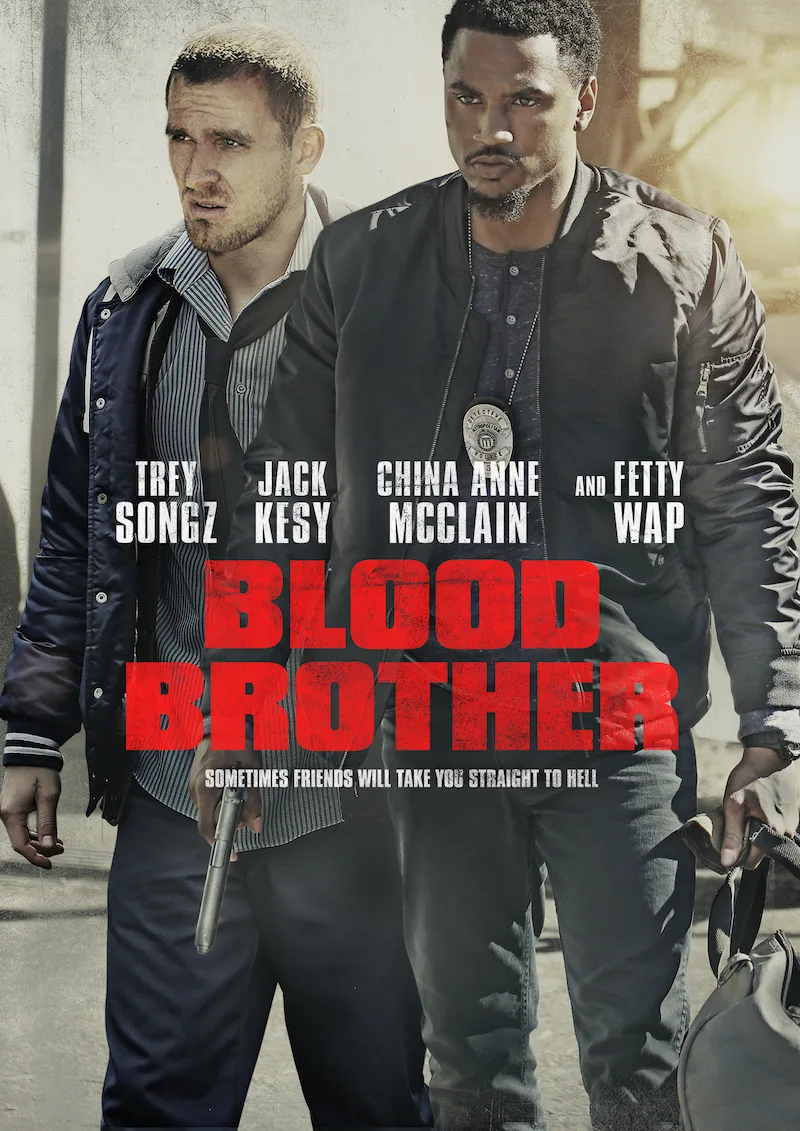

Fifteen years later, Sonny (Tremaine “Trey Songz” Neverson), the de facto leader of the old gang, has become a police detective with a fine record and a broken marriage to Megan (Tanee McCall) to show for it. Jake (Jack Kesy), the guy who took the fall for his buddies, is being released from prison. Sonny goes to pick up his old friend, but in a power play that primarily sets up an additional number of people shooting during the climax, Jake has called his brothers to bring him home without telling Sonny.

Tensions ease when Jake calls Sonny and the other two friends (played by Hassan Johnson and J.D. Williams)—who don’t matter here, until they really don’t matter—to split the stolen money. Sonny and Jake seem to be pals again, with Jake wanting to go with Sonny to a music recital for Megan’s younger sister Darcy (China Anne McClain). Along the way, the two stop at a corner store, where Jake viciously murders the employees and goes on the run.

The prologue and brief first act of Michael Finch, Karl Gajdusek, and Charles Murray’s screenplay gives the impression that the screenwriters might have something to say about these characters, their relationship, and the conditions that have led them to this place. The introduction sets up a promising dichotomy between Sonny and Jake, as the reformed friend suggests that the recently incarcerated one might be able to turn around his life.

Instead, though, the screenwriters dismiss all of that potential as soon as Jake reveals himself to be a cold-blooded, unforgivable killer, who sets out to murder the other two friends, to befriend—and, later, kidnap—the underage Darcy, and otherwise to toy with Sonny instead of outright killing him (he has multiple chances to do so but doesn’t, because, as he says, it would ruin the fun, which just seems like a cheap, inexplicable rationale for the screenwriters to drag out the material). Meanwhile, Sonny—whose shaky moral/ethical code is teased but never examined or criticized—has to deal with assorted criminals who might know where Jake is, while also keeping his criminal past a secret from an increasingly suspicious (but almost entirely ineffective) police force.

This might seem like a lot of juggling, but all of the complications are excuses for standoffs (usually with the two men pointing guns at each other, despite the fact that neither has a desire to kill the other) and a couple of action sequences. A half-hearted car chase is particularly laughable for the complete lack of any other cars on a four-lane highway, just one of many ways director John Pogue doesn’t let a restricted budget get in the way of checking off the obligatory requirements for such a movie.

To be sure, there isn’t a single, underdeveloped conflict here that isn’t at least partially resolved with an outburst of gunfire. It’s a long way from where “Blood Brother” begins—appearing to have some consideration for its characters and their predicaments. Instead, the movie ultimately lets the guns do the talking.