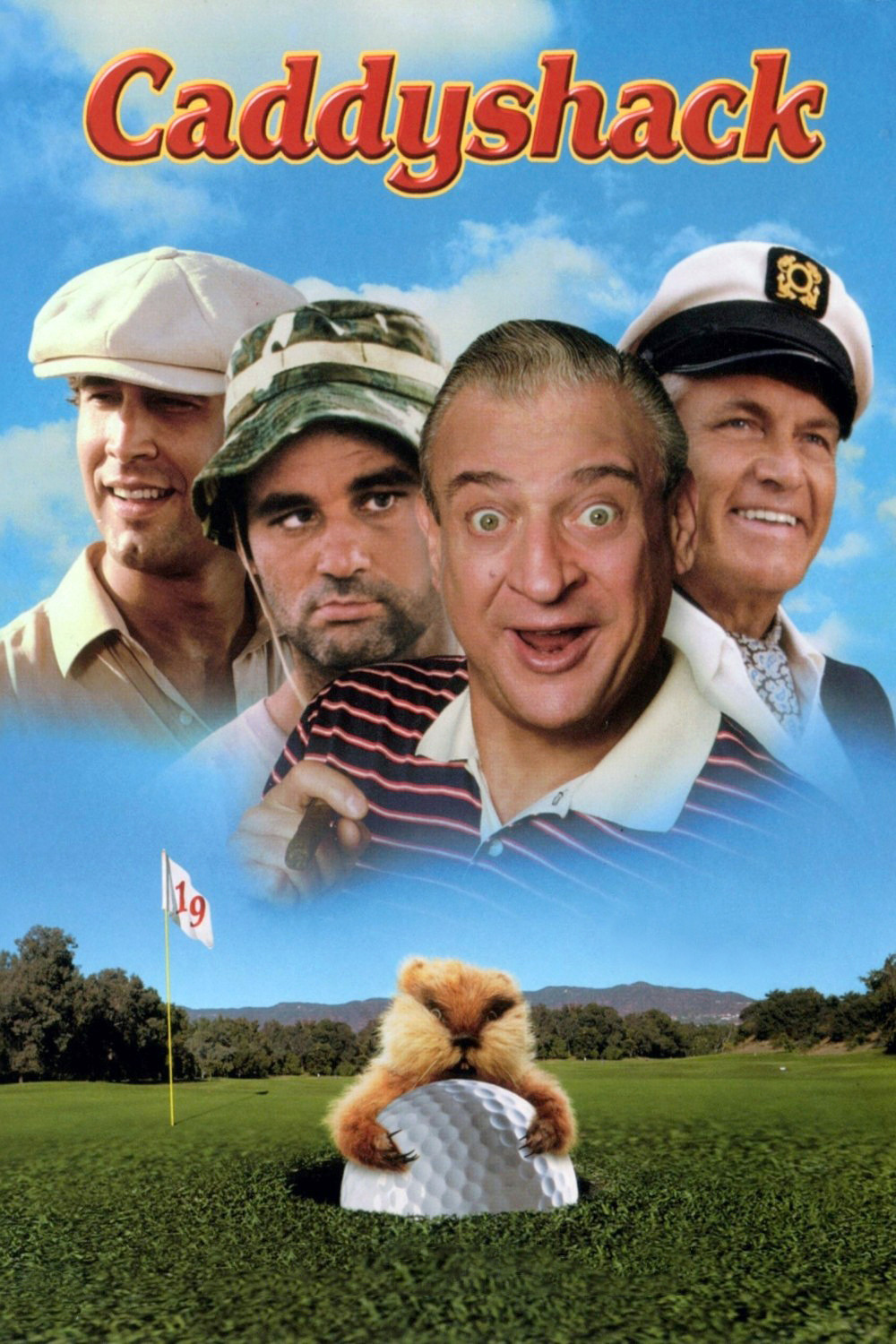

“Caddyshack” never finds a consistent comic note of its own,

but it plays host to all sorts of approaches from its stars, who sometimes

hardly seem to be occupying the same movie. There’s Bill Murray‘s self-absorbed

craziness, Chevy Chase‘s laid-back bemusement, and Ted Knight’s apoplectic

overplaying. And then there is Rodney Dangerfield, who wades into the movie and

cleans up.

To the degree that this is anybody’s movie, it’s

Dangerfield’s_and he mostly seems to be using his own material. He plays a

loud, vulgar, twitching condo developer who is thinking of buying a country

club and using the land for housing. The country club is one of those exclusive

WASP enclaves, a haven for such types as the judge who founded it (Knight), the

ne’er-do-well club champion (Chase), and the manic assistant grounds keeper

(Murray).

The movie never really develops a plot, but

maybe it doesn’t want to. Director Harold Ramis brings on his cast of

characters and lets them loose at one another. There’s a vague subplot about a

college scholarship for the caddies, and another one about the judge’s nubile

niece, and continuing warfare waged by Murray against the gophers who are

devastating the club. But Ramis is cheerfully prepared to interrupt everything

for moments of comic inspiration, and there are three especially good ones: The

caddies in the swimming pool doing a Busby Berkeley number, another pool scene

that’s a scatalogical satire of Jaws, and a sequence in which Dangerfield’s

gigantic speedboat devastates a yacht club.

Dangerfield is funniest, though, when the movie

just lets him talk. He’s a Henny Youngman clone, filled with one-liners and

insults, and he’s great at the country club’s dinner dance, abusing everyone

and making rude noises. Surveying the crowd from the bar, he uses lines that he

has, in fact, stolen directly from his nightclub routine (“This steak

still has the mark of the jockey’s whip on it”). With his bizarre wardrobe

and trick golf bag, he’s a throwback to the Groucho Marx and W.C. Fields school

of insult comedy; he has a vitality that the movie’s younger comedians can’t

match, and they suffer in comparison.

Chevy Chase, for example, has some wonderful

moments in this movie, as a studiously absent-minded hedonist who doesn’t even

bother to keep score when he plays golf. He’s good, but somehow he’s in the

wrong movie: His whimsy doesn’t fit with Dangerfield’s blatant scenery-chewing

or with the Bill Murray character. Murray, as a slob who goes after gophers

with explosives and entertains sexual fantasies about the women golfers, could

be a refugee from Animal House.

Maybe one of the movie’s problems is that the

central characters are never really involved in the same action. Murray’s off

on his own, fighting gophers. Dangerfield arrives, devastates, exits. Knight is

busy impressing the caddies, making vague promises about scholarships, and

launching boats. If they were somehow all drawn together into the same story,

maybe we’d be carried along more confidently. But “Caddyshack” feels more like

a movie that was written rather loosely, so that when shooting began there was

freedom, too much freedom, for it to wander off in all directions in search of

comic inspiration.