On Nov. 16, 1959, Truman Capote noticed a news item about four members of a Kansas farm family who were shotgunned to death. He telephoned William Shawn, editor of The New Yorker, wondering if Shawn would be interested in an article about the murders. Later in his life, Capote said that if he had known what would happen as a result of this impulse, he would not have stopped in Holcomb, Kan., but would have kept right on going “like a bat out of hell.”

At first Capote thought the story would be about how a rural community was dealing with the tragedy. “I don’t care one way or the other if you catch who did this,” he tells an agent from the Kansas Bureau of Investigation. Then two drifters, Perry Smith and Richard Hickock, are arrested and charged with the crime. As Capote gets to know them, he’s consumed by a story that would make him rich and famous, and destroy him. His “non-fiction novel,” In Cold Blood, became a best seller and inspired a movie, but Capote was emotionally devastated by the experience and it hastened his death.

Bennett Miller’s “Capote” is about that crucial period of less than six years in Capote’s life. As he talks to the killers, to law officers and to the neighbors of the murdered Clutter family, Capote’s project takes on depth and shape as the story of conflicting fates. But at the heart of his reporting is an irredeemable conflict: He wins the trust of the two convicted killers and essentially falls in love with Perry Smith, while needing them to die to supply an ending for his book. “If they win this appeal,” he tells his friend Harper Lee, “I may have a complete nervous breakdown.” After they are hanged on April 14, 1965, he tells Harper, “There wasn’t anything I could have done to save them.” She says: “Maybe, but the fact is you didn’t want to.”

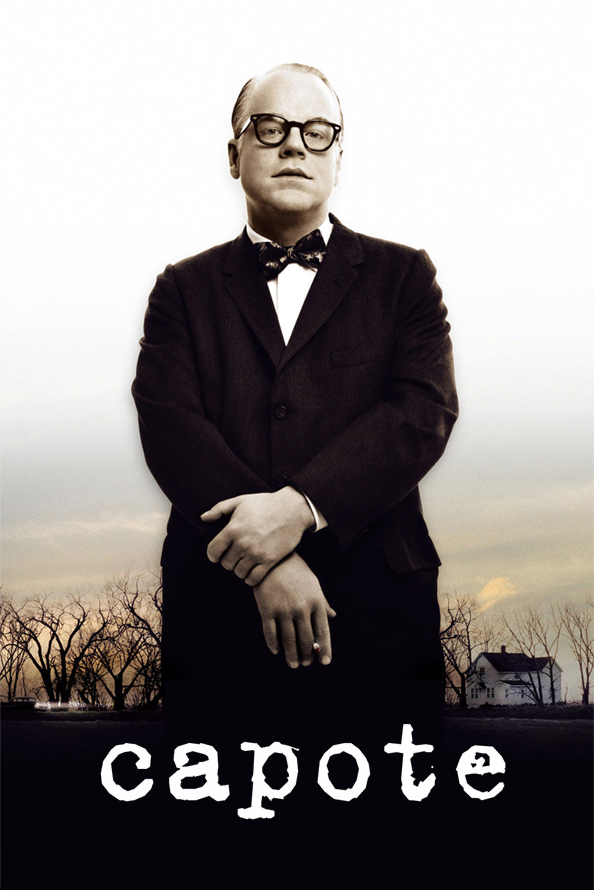

“Capote” is a film of uncommon strength and insight, about a man whose great achievement requires the surrender of his self-respect. Philip Seymour Hoffman’s precise, uncanny performance as Capote doesn’t imitate the author so much as channel him, as a man whose peculiarities mask great intelligence and deep wounds.

As the story opens Capote is a well-known writer (of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, among others), a popular guest on talk shows, a man whose small stature, large ego and affectations of speech and appearance make him an outsider wherever he goes. Trying to win the confidence of a young girl in Kansas, he tells her: “Ever since I was a child, folks have thought they had me pegged, because of the way I am, the way I talk.” But he was able to enter a world far removed from Manhattan, and write a great book about ordinary Midwesterners and two pathetic, heartless killers. Could anyone be less like Truman Capote than Perry Smith? Yet they were both mistreated and passed around as children, had issues with distant and remote mothers, had secret fantasies. “It’s like Perry and I grew up in the same house, and one day he went out the back door and I went out the front,” he tells Harper Lee.

The film, written by Dan Futterman and based on the book the book Capote by Gerald Clarke, focuses on the way a writer works on a story and the story works on him. Capote wins the wary acceptance of Alvin Dewey (Chris Cooper), the agent assigned to the case. Over dinner in Alvin and Mary Dewey’s kitchen, he entertains them with stories about John Huston and Humphrey Bogart. As he talks, he studies their house like an anthropologist. He convinces the local funeral director into letting him view the mutilated bodies of the Clutters. Later, Perry Smith will tell him he liked the father, Herb Clutter: “I thought he was a very nice, gentle man. I thought so right up until I slit his throat.”

On his trips to Kansas he takes along a southern friend from childhood, Harper Lee (Catherine Keener). So long does it take him to finish his book that Lee in the meantime has time to publish her famous novel To Kill a Mockingbird, sell it to the movies, and attend the world premiere with Gregory Peck. Lee is a practical, grounded woman who clearly sees that Truman cares for Smith and yet will exploit him for his book. “Do you hold him in esteem, Truman?” she asks, and he is defensive: “Well, he’s a gold mine.”

Perry Smith and Dick Hickock are played by Clifton Collins Jr. and Mark Pellegrino. Hickock is not developed as deeply as in Richard Brooks’ film “In Cold Blood” (1967), where he was played by Scott Wilson; the emphasis this time is on Smith, played in 1967 by Robert Blake and here by Collins as a haunted, repressed man in constant pain, who chews aspirin by the handful and yet shelters a certain poetry; his drawings and journal move Capote, who sees him as a man who was born a victim and deserves, not forgiveness, but pity.

The other key characters are Capote’s lover, Jack Dunphy (Bruce Greenwood), and his editor at the New Yorker, William Shawn (Bob Balaban). “Jack thinks I’m using Perry,” Truman tells Harper. “He also thinks I fell in love with him in Kansas.” Shawn thinks In Cold Blood, when it is finally written, is “going to change how people write.” He prints the entire book in his magazine.

The movie “In Cold Blood” had no speaking role for Capote, who in a sense stood behind the camera with the director. If “Capote” had simply flipped the coin and told the story of the Clutter murders from Capote’s point of view, it might have been a good movie, but what makes it so powerful is that it looks with merciless perception at Capote’s moral disintegration.

“If I leave here without understanding you,” Capote tells Perry Smith during one of many visits to his cell, “the world will see you as a monster. I don’t want that.” He is able to persuade Smith and Hickock to tell him what happened on the night of the murders. He learns heartbreaking details, such as that they “put a different pillow under the boy’s head just to shoot him.” Capote tells them he will support their appeals and help them find another lawyer. He betrays them. Smith eventually understands that, and accepts his fate. “Two weeks, and finito,” he tells Capote as his execution draws near. Another good line for the book.