Roger Ross Williams’ “Cassandro” pays tribute to that pioneering legacy born out of one of Mexico’s most popular exports, lucha libre. But despite its flamboyant hero, this underdog sports story feels strangely conventional.

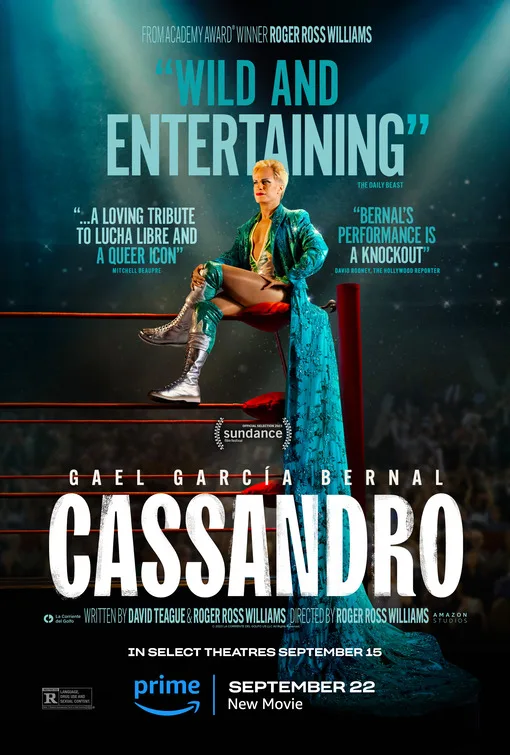

Co-written by Williams and David Teague, “Cassandro” follows the rise of Saúl Armendáriz, a lucha libre wrestler who finds success when he leaves behind traditional luchador dreams and begins fighting as an exótico, or a male wrestler who performs in drag. Saúl (Gael García Bernal) takes inspiration from a telenovela playing at a diner to create his new ringside persona Cassandro, and with the help of trainer Sabrina (Roberta Colindrez), his supportive mom Yocasta (Perla De La Rosa), an ambitious promoter Lorenzo (Joaquín Cosío), and a lover named Gerardo (Raúl Castillo), Saúl rises through the ranks to become a national sensation facing off with lucha libre royalty, El Hijo del Santo.

Cassandro could have been played as the Liberace of lucha libre, but Williams’ film doesn’t quite commit to the theatrical potential of his character or his story. It’s too serious, straightforward, and like a standard biopic—and this is about a lucha libre wrestler! We are here for the performance, the fun, the rooting for our heroes, and the fantasy of good vs. evil. Instead of feeling like a fight to the top, a la “Rocky,” or the anarchistic comedy of “GLOW,” the arc in “Cassandro” is a gentle climb up, relatively painless and quick.

For a movie so dedicated to identity, “Cassandro” only lightly tussles with everything happening in Saúl’s life. His doting mother encourages him to get a boyfriend early on, but a few scenes later, she blames him for coming out and driving away his father. Unfortunately, they never discuss her hesitant support for him. There’s also the unspoken issue that Saúl, a Mexican American from El Paso, Texas, is coming to Mexico to step into his true identity. He’s a “ni de aquí, ni de allá” kid, someone who straddles both cultures and struggles to be accepted by either side. For any American-born children of immigrants, it is usually one of the first things cousins back home will tease you about, and I’m sure sports fans would as well, but it’s never really mentioned as a part of his story. Considering the inter-cultural furor that bubbled over Mexican-American boxer Oscar de la Hoya when he fought the Mexican-born Julio César Chávez, it seems like a vital piece of the story went missing in this telling.

However, Williams does explore the enormity of what it meant for Saúl to be openly gay at a time when it was not as publicly accepted in a macho sport, with fans often calling him homophobic slurs. As Cassandro, Saúl chooses to play a character that enhances his femininity, costumes and makeup included. He literally and figuratively “unmasks” himself by ditching the luchador mask and taking up the campy moves and flair of an exótico with one caveat: he’s not just there to play the clown. He’s there to win. Using Sabrina’s techniques and training to overpower his larger, more macho opponents, his performance becomes as big a statement as putting on a cape and cat eyeliner to strut into the ring. He can win and no longer be the butt of jokes. Even if he doesn’t win, Cassandro gives the audience quite a show—so much that they cheer for him instead of the masked hero he’s fighting.

As Saúl/Cassandro, García Bernal commits to playing the underdog in all his vulnerability and strength. He relishes in playing Cassandro at his most flamboyant, even bringing a sense of agility and speed to the ring against his bigger, lumbering opponents who are incapable of matching him. I’m excited to see Colindrez get more attention after her work on TV shows like “Vida” and “A League of Their Own.” While she plays a subdued supporting role here, she becomes a useful companion to García Bernal’s Saúl, a mentor and friend in addition to being a wrestler in her own right. She also becomes the audience’s proxy in a crowd primed to hate people like Cassandro.

As fellow luchador Gerardo, Castillo is a smoldering pillar of mystery. No wonder Saúl can’t look away. Unfortunately, Gerardo is also wrestling with his desires and what to do with his family. The sexual tension Castillo brings to the role is an antidote to how the movie stops for a drug dealer named Felipe (Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, aka Bad Bunny, one of the biggest names in music right now). It brings me no joy to report that this stunt casting is a flop, even with his limited screen time. Benito looks lost in his role, and even his kiss with García Bernal is lackluster.

While “Cassandro” is not a winner, Williams and his cast put up enough of a show to make things interesting. García Bernal is so earnest in his performance, and supporting actors like Colindrez and Castillo bring plenty of tension and emotion to events outside the ring. Williams and cinematographer Matias Penachino liven things up with creative choices like a spinning backyard training montage, staging an emotional scene like an oil painting, and changing cameras at the end to make Cassandro’s national showdown feel more like a live sporting event.

“Cassandro” even includes “Hasta Que Te Conoci” by Juan Gabriel, Mexico’s equivalent to Liberace, who, like the piano man himself, never publicly answered if he was homosexual or not. (Instead, Gabriel famously answered in an interview, “Lo que se ve no se pregunta” [“What one sees doesn’t have to be asked about”]). As part of the next generation of entertainers, Cassandro was unafraid to embrace his identity as part of his performance, setting the stage for future artists to do the same.

Now playing in select theaters and available on Prime Video on September 22nd.