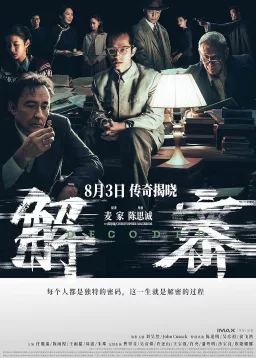

Last year, Hong Kong filmmaker Herman Yau directed at least two of the best action movies of the year. In the 1990s, Yau (“Ebola Syndrome,” “The Untold Story”) helmed sensational black comedies and/or true-crime thrillers about psychopathic skid row loners, some of which are now finding new audiences on American Blu-ray boutique labels. Today, Yau directs Hong Kong and/or mainland China-financed action movies, often focused on a team of diligent, but stressed-out law enforcement officials.

“Customs Frontline,” a Hong Kong procedural that pits the local customs department against a ring of international weapons dealers, continues this trend. It’s also unusual given that it’s not only a star vehicle for Nicholas Tse, but also the first project that Tse’s worked on as the primary action choreographer. “Customs Frontline” is not quite as thrilling or as relentless as Yau’s other recent successes—particularly “Moscow Mission” and “Raid on the Lethal Zone”—but it still delivers more twists and surprises than you might expect from this type of sudsy, formulaic cop drama.

In “Customs Frontline,” Tse plays Chow Ching-lai, a frustrated but loyal Customs Department officer on the trail of the mysterious Dr. Raw (Amanda Strang), a well-connected arms dealer smuggling guns and other weapons through Hong Kong. Chow wants to nab Dr. Raw for personal reasons that coincide with his professional responsibilities since Raw’s operation was being pursued by Cheung Wan-nam (Jacky Cheung), Chow’s unstable but sympathetic boss. I say “was” because Cheung suffers an unfortunate fate early on in the movie.

Cheung not only urges Chow to take his job more seriously—“Respect your uniform!”—but also inspires his subordinate by persevering despite a previously undisclosed bipolar diagnosis. Cheung also discovers a well-positioned mole within the Customs Department, leaving Chow to figure out how to stop Raw, who’s currently arming the clashing (and fictional) African nations of Hoyana and Loklamoa.

The first half or so of “Customs Frontline” sets up Cheung’s character as a figurehead for his department, plagued as it is by a generic sort of bureaucracy, largely represented by Kwok Chi-keung (Francis Ng), the bureau’s paternal, but unfriendly co-commissioner. A handful of shoot-outs and chase scenes break up these unusually drawn-out establishing scenes, most of which coast on Cheung’s charismatic performance. Still, while it takes a moment before Tse’s character takes over his own movie, his fight choreography eventually gets a decent showcase.

It also helps to see the movie’s action scenes as punctuation for its kitchen-sink style of hard-boiled action. Every character has a backstory, including Dr. Raw, and they’re mostly endearing despite a lack of psychological or emotional complexity. Instead, a pile-on of pulpy twists and turns makes “Customs Frontline” a largely compelling potboiler. Both parts of the movie, the one led by Cheung and the one led by Tse, feature unusual details that will leave you guessing, like: why are we still talking about Cheung’s emotional intelligence, or who is Dr. Raw’s dad, beyond a supposedly beloved and respected weapons smuggler? There are crypto-currency bribes, a violent suicide, presumed inter-departmental sabotage, and, oh yeah, sometimes computer-generated cargo ships and tank-sized jeeps explode or flip over from end to end.

Tse shows promise during his fight scenes, though his choreography’s never as convincing as his stolid body language and shameless action figure poses. He’s a little too stiff to carry the movie on his own, but he gets a lot of help from his co-stars, including Karena Lam, who plays Customs department officer Athena Siu, Cheung’s patient, devoted partner.

Yau’s still the real MVP of “Customs Frontline,” given his comfort and knack for unabashed sensationalism. Car stunts, including a chase where one vehicle gets boxed in by four others, often bring out the best in the movie, but they’re not the only standout moments. Yau notably brings out the best in his actors, particularly Cheung, whose extreme close-ups highlight his repertory of mercurial facial expressions. Yau also has a gift for escalating violence, which isn’t nothing given the probable limits he had to work with as a Hong Kong filmmaker who, like a lot of his peers, now has to cater to the mainland Chinese market and its government’s influence. In the 1990s, Yau stood out from his peers with trend-chasing thrillers. The Hong Kong film industry may have changed considerably since then, but Yau’s still doing what he does.

If anything, what’s most impressive about “Customs Frontline” is that it never slows down long enough for you to question its sketchy, cornball logic. “Customs Frontline” may not make much sense, and it doesn’t exactly move with fluidity or grace, but it does move, and often hard and fast enough to get you from one spectacular flare-up to the next with style and chutzpah to spare.