Inadequacy peeks from behind the uncomfortable smiles and passive aggressive remarks that two adult men exchange in the presence of the 13-year-old boy under their care. Both of these visibly distressed would-be role models is desperate for some validation. The father, Jim (Colin Burgess), has driven his adolescent son Branson (played by boyish-looking adult actor Brian Fiddyment) to a home nestled inside a forest where Dave (Anthony Oberbeck), the kid’s overly involved stepdad, is waiting for them. Suzie (Clare O'Kane), the woman that connects the male trio, is set to arrive later in the weekend.

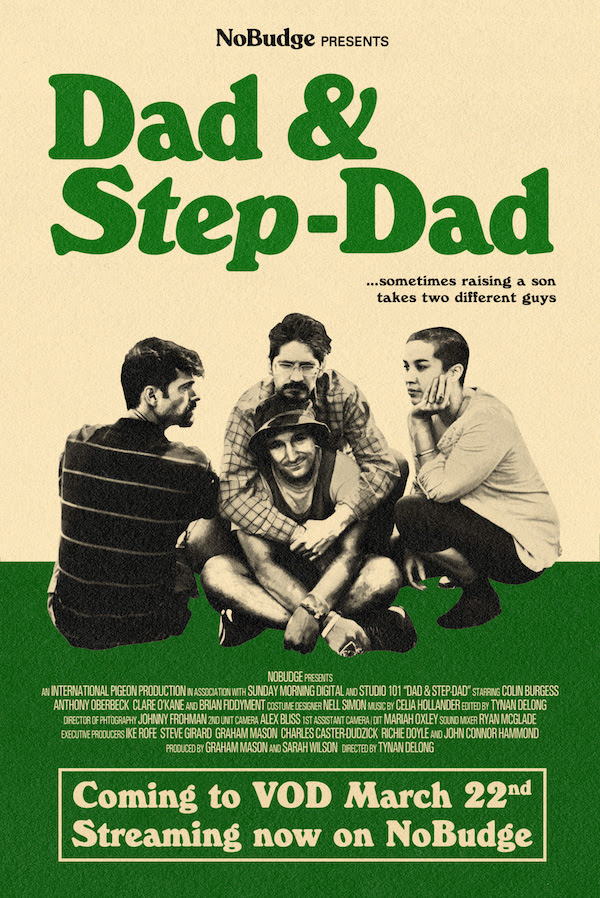

That’s the simple but effective setup of the consistently laugh-out-loud and unexpectedly poignant microbudget deadpan comedy “Dad & Step-Dad,” from filmmaker Tynan DeLong. The feature expands on a series of short films starring these characters, played by the same actors, that DeLong created over the last few years. The concept is reminiscent of the childish feuding between the protagonists in Adam McKay’s “Step Brothers” but filtered through the down-to-earth, far less in-your-face sensitivities of mumblecore filmmaking.

Amid the tranquility of nature—expressed in idyllic cutaway shots of the surrounding flora and fauna—the two guys fight over every petty opportunity to assert their superiority in the eyes of Branson, who doesn’t much care about their juvenile, but mostly restrained competitiveness. Neither David nor Jim embody the hypermasculine bro-type to get physically violent, but rather a defeated pair of dudes approaching middle age and on the verge of snapping. Under a veneer of politeness, they argue about the grill’s temperature or whose approach to playing guitar is best suited to accompany Branson’s freestyle rapping.

The humor derives from the self-seriousness of the line delivery, always without a hint of irony, and the uneasy silence that follows some of the most outrageous sentences uttered. A conversation on masturbation, a subject where Dave and Jim’s beliefs differ radically, turns into an interrogation of both Branson’s unusual desires and the most appropriate technique for self-pleasure. As preposterously awkward as the presentation of these parental dilemmas is, the underlying commonality is that they each exemplify how the men are projecting their own sense of failure onto the boy. It’s about them and not Branson.

The not-so-inconspicuous subtext of Dave’s optimistic outlook on life and Jim’s guilt over his initially hostile demeanor push DeLong’s debut over the fence of mere parody and into the realm of storytelling with characters exhibiting recognizable inner troubles. That is to say that “Dad & Step-Dad” is the rare movie that reveals itself more intellectually and emotionally rich than it purports to be on the surface, as opposed to the other way around, which happens quite frequently. The DIY manufacturing of “Dad & Step-Dad,” where the cast wears other crew hats, never calls negative attention to itself because the story has been conceived to exist not in spite of but within a set of specific limitations: a location that’s inherently visually dynamic and a group of actors with rapport built over a long time working together that allows them to construct compelling interactions from thin air.

There’s a wounded earnestness to Oberbeck’s performance that elevates it just a little higher than those of his counterparts. It also helps that the turmoil that afflicts his character—his relationship with the level-headed Suzie is on shaky ground—lends itself to more solemn acting. The dramatic register of Burgess feels just a tad closer to sketch comedy, which creates a dissonance necessary for the humor to work. Both Oberbeck and Burgess serve as co-writers and co-editors of the film, and while DeLong isn’t interested in filling us in on what came before or after this getaway, the evenly matched back and forth between the two convinces that there are lived-in layers to this bond. We are just witnessing the turning point in their frenemy arc. That Fiddyment plays Branson, also with utter sincerity, is a choice that feels not only practical, but thematically relevant as it points out that an immature personality can live inside a grown-up body—think man-child. We don’t simply become wise and leave behind our unflattering impulses when we grow older.

As with plenty of memorable comedies, what makes “Dad & Step-Dad” a special treat is that beneath its well-mannered raunchiness and stoic silliness there’s an undercurrent of something truthful about the human condition. It’s when rivalry morphs into a sincere bromance that DeLong, Burgess, Oberbeck allow the movie to grapple with men’s vulnerability without pulling the rug from under us. “What’s it all about, man?” Jim asks Dave after a shared moment of genuine connection. There’s no answer, but what DeLong tacitly gets at is that parents are simply kids that grew up and who don’t automatically gain an infallible manual on how to navigate the unforgiving waters of everyday existence.

That doesn’t change at the end of “Dad & Step-Dad,” but now these two average father figures don’t have to go through it alone. Wherever their unconventional family goes from here, looking after Branson is a great reason for them to hang out and fend off the darkness inside one stupidly inconsequential, yet amusing act one one-upmanship at a time.