“Mom, this summer, could you teach me how to fly?”

This is what I asked at age 4 while walking out of Chicago’s Arie Crown Theater after having seen Cathy Rigby, suspended on wires, soaring into the audience while throwing out handfuls of fairy dust. This image of literature’s eternal youth Peter Pan, as portrayed in the 1990 revival of the hit musical immortalized on television by Mary Martin, remains one of my earliest vivid memories. Little did I know that another kid well-acquainted with the show had already hatched an idea that would inspire one of the most poignant, popular and polarizing adaptations of J.M. Barrie’s 1904 play, Peter Pan, and its immortal 1911 novelization originally titled Peter and Wendy.

Jake Hart grew up with the same versions of Peter Pan that most children of my generation did, perhaps most notably the 1953 animated classic from Disney. When I recently spoke with him along with various other subjects for this retrospective via Zoom, he insisted that Barrie’s story wasn’t much more a part of his family’s life than any other fantasy. Yet it was during a fateful conversation with his father, screenwriter James V. Hart, his mother, Judy, and his sister, future filmmaker Julia, that Jake saw the potential in expanding the beloved narrative beyond what had already been explored time and time again.

“I was in desperate need of employment, so I played a game with my family at the dinner table called ‘What if?’, where we would stand fairy tales on their head,” recalled James. “What if Cinderella’s glass slipper didn’t fit? Or what if it broke? What if Prince Charming had bad breath and Sleeping Beauty wouldn’t kiss him? What if the ring didn’t fit Frodo’s finger? What if Harry Potter was a bad magician, and ended up doing bat mitzvahs and birthday parties? We would come up with an answer that would spin the story in a different direction. And one night, Jake—who was 5 at the time—asked, ‘Did Peter Pan ever grow up?’ Being the stodgy parent that I was, I got kind of huffy and replied, ‘What a stupid question. Of course he didn’t grow up!’ But Jake was adamant and said, ‘Yeah, but what if Peter did grow up?’

Suddenly, the bells and whistles began to go off in my head, because for years, people had been trying to make ‘Peter Pan.’ Steven Spielberg was rumored to have wanted to make a musical with Michael Jackson, Francis Coppola tried to make his version and John Hughes wrote a ‘Peter Pan’ script that took place during WWII, but they all rehashed the same story about the Darlings going back to Neverland. What Jake did was open up a window to my generation who grew up with Mary Martin and Walt Disney’s versions, and suddenly I was like, ‘Wow, what if Peter Pan grew up? He’d turn out to be like us—he would have forgotten how to fly and become a capitalist.’ So that night, we decided that the worst thing we could do to Peter Pan would be to make him a lawyer, because I was surrounded by big attorneys and Wall Street guys and hedge fund operators. I was the only father in our community who didn’t own a suit and tie, so that night, we actually sat down as a family and we cobbled out a story right there.”

The ten-page treatment that materialized from this family conversation was pitched by James all over Hollywood, and was turned down by everyone. One executive told him, “I’m very moved by your story. It’s incredible. But I don’t believe that grown-ups can fly.” Once Lasse Hallström expressed interest in directing his own version of “Peter Pan,” James’ agents lost interest in his script, though his family proceeded to torture him every Christmas by giving him Pan-themed gifts. Despite working on two scripts that would ultimately make him a respected name in Hollywood—“Hook” and “Bram Stoker’s Dracula”—the Creative Arts Agency (CAA) fired him, believing neither of these projects would ever get made.

“My sister and I grew up in the writer’s life where we were used to unemployments more than employment,” recalls Jake. “We knew what dad did, but at that age, nothing had been made. Sometimes dad would come out to LA for two or three months to hit the pavement and get a job, so we became used to the routine of another big work trip coming up. I had friends with parents who had nine to five jobs, but that wasn’t at all what I experienced at home. There was an openness in every aspect of the family dynamic in terms of schedule and commitments. My sister and I never dealt with our parents asking us, ‘Are you sure you don’t want to get a job job?’, though I do remember when I started suggesting that I may want to pursue screenwriting, and my father’s basic reaction was, ‘Are you out of your fucking mind? Don’t you see the bullshit I deal with all the time?’”

After writing a sci-fi script for producers Craig Baumgarten and Gary Adelson, James was asked by them if he had a favorite project that everybody had passed on. When James gave Baumgarten and Adelson the treatment for “The Revenge of Captain Hook,” they connected the writer with Nick Castle, the actor/director renowned for his portrayal of Michael Myers in John Carpenter’s original “Halloween.” In addition to having helmed 1984’s family friendly adventure “The Last Starfighter,” he also directed a film James had loved, 1986’s “The Boy Who Could Fly,” about an autistic boy who dreams of defying gravity.

Encouraged by the head of TriStar, Jeff Sagansky, to develop the project, James and Castle spent a year working on the script. The first draft took place in New York, since the studio didn’t want to have the story set in Barrie’s original location of London, where Peter whisked Wendy Darling and her siblings out of their beds and on to Neverland. It wasn’t until the second draft that they agreed switching the story to London was the correct choice. The project appeared doomed when Sagansky was replaced by Mike Medavoy, a changing of the guard that typically flings any project in development out the window. Yet without the writers’ knowledge, Medavoy and CAA sent the “Hook” script to five of Hollywood’s top directors, giving them one weekend to read it and say yes in an attempt to woo a name with more industry cred than Castle.

“Judy, Jake, Julia and I were in Wyoming, visiting friends who had loaned me money to get through the writing of ‘Hook,’ while we rented out our apartment,” said James. “We were having hamburgers at Cadillac Jack’s, and I went down to a pay phone to check in with my answering machine. My agent had called and told me to return his call as soon as possible. So I did immediately, and he said, ‘There’s a very big director interested in doing ‘Hook,’’ and I said, ‘But we have a director, Nick Castle.’ He answered, ‘Yes, but this director is huge.’ I replied, ‘If it’s not Steven Spielberg, then we have nothing to talk about,’ and he said, ‘That’s who it is.’ I was speechless. I hung up the phone, went back upstairs and sat down at the table, trying to stay calm. Judy asked, ‘Well, anything happening?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, Steven Spielberg is going to direct ‘Hook.’’ Mic drop. They had loved Nick and my second draft, which was the one everybody read, and it went from there, like a rocket.”

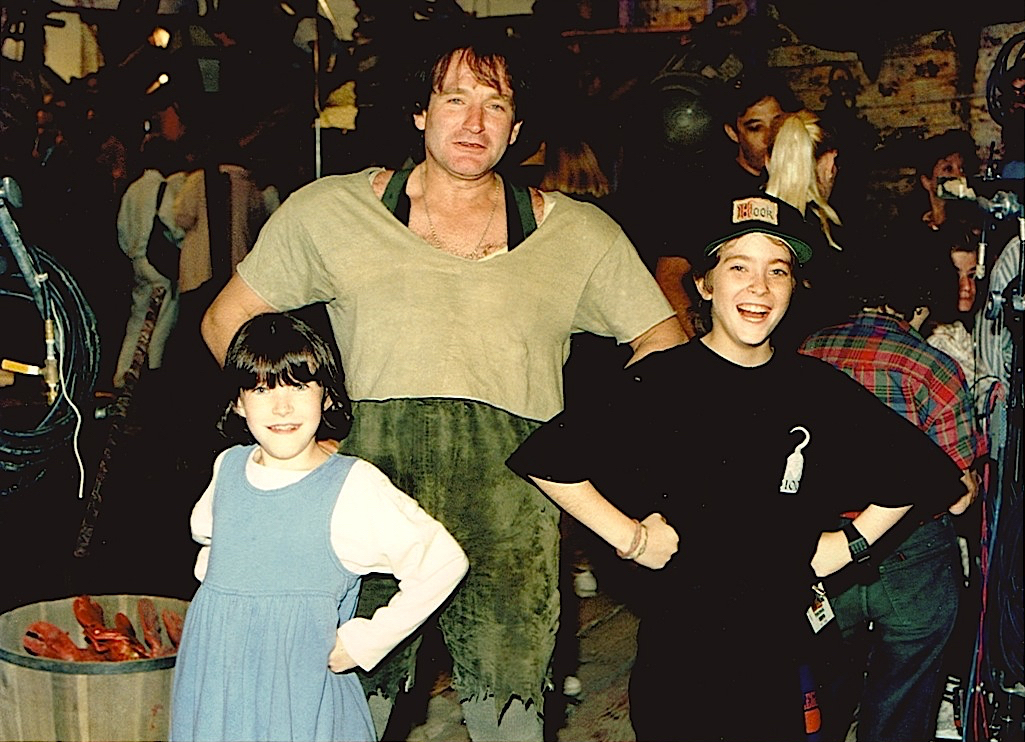

Though Castle didn’t want his name attached to the project, James insisted that he receive story credit, noting that his fingerprints are felt throughout the script as well as the completed film. Castle later quipped that the very handsome settlement he received paid for his Prozac. Ultimately titled “Hook,” the script centered on Peter Banning (Robin Williams), a.k.a. the grown-up Peter Pan, a workaholic father with no memory of his adventures in Neverland. When his children Jack (Charlie Korsmo) and Maggie (Amber Scott) are kidnapped by his “great and worthy opponent” Captain Hook (Dustin Hoffman) in an attempt to inspire a rematch, Banning is forced to reconnect with his inner child.

Jake says that it’s no coincidence the name Jack isn’t all that far removed from his own, nor the fact that the character’s love of baseball reflects his own childhood interests. His sister Julia also happened to have, like Maggie, a teddy bear she had nicknamed “Taddy.” “The neglect that Jack feels is where my dad had to get creative because the support I had from him, whether I was pursuing sports or the arts, never faltered,” Jake affirmed. James also created a wholly original character that proved to be a legend in his own right: the leader of the Lost Boys, Rufio, a role that made an instant star out of Filipino American actor Dante Basco.

“I remember originally hearing that Robin Williams was playing a grown-up Peter Pan, and that captured the imagination of everyone around Hollywood at the time, as well as the fact that it was being directed by Steven Spielberg,” said Basco. “Spielberg and Williams were both the grown-up versions of Peter Pan. I actually remember calling my manager at the time and saying, ‘I’d like to audition for anything in that movie.’ I didn’t know I was going to end up being the leader of the Lost Boys. I just wanted to be a part of the biggest thing going on at the time, and this project seemed so magical. By the time I was cast in ‘Hook,’ I had already been acting for five years, so I was a young kid veteran of the business. Yet in many ways, I’m still considered to have been discovered by Spielberg, which obviously propelled me to a different kind of stature within the Hollywood realm by showing I could hold my own with legends like Williams and Hoffman. It changed my life.”

With already a few major films under his belt, Korsmo had managed to build an impressive acting career that was spurred by his need to escape school, which he loathed. While on a family vacation in Los Angeles, he attended a taping of “Punky Brewster” and felt that the job of an actor looked both easy and fun, so he asked his parents to help him get work in commercials once they returned home to Minneapolis. His short yet indelible career as a child actor enabled him to avoid spending fifth through seventh grade with his peers.

“Those are the years when kids are at their meanest,” said Korsmo, whose breakout role was as The Kid in Warren Beatty’s 1990 blockbuster, “Dick Tracy.” “It’s sort of like a genteel prison where teachers are basically trying to keep the students from harming one another for eight hours a day. Acting enabled me to trade in that environment for one in which I was treated as a contributor and a colleague, rather than a ward, by an amazing group of adults at the top of their fields. I was around the ages my children are now—9 and 11—when I made ‘Dick Tracy,’ and I looked younger than I was, so I really bristled at being treated like a kid, but Warren made me feel like a part of the crew. He’d have me there with him and the cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro, when they would be blocking scenes for the day’s shoot. I was never made to feel like a prop, and the same was true of my experience on ‘Hook.’”

Though opinions have varied on “Hook” over the years, one thing most viewers agree on is that the opening half-hour in which Peter and his family travel to London is bravura filmmaking, anchored by Williams’ surprisingly restrained portrayal of a lawyer more focused on securing a work deal than paying attention to his children.

“There’s something about Robin’s performance where from moment one, you can tell that there is a pain within this guy that is coming out the wrong way,” said Jake. “It’s not that he has a genuine lack of empathy or interest or self-involvement. It’s just that something is wrong, and even he doesn’t know what it is. It’s so clear that he’s the sort of guy who doesn’t want to be yelling at his kids. He just doesn’t know what else to do with whatever it is that he’s feeling. A lot of times you kind of wait for that turn in which the happy version of a person will emerge. But he was both of those people at once. One just happened to be dominating until the other was allowed to fly.”

Effortlessly going toe-to-toe with Williams was Korsmo as Peter’s disillusioned son. Having already memorably collaborated with Beatty in “Dick Tracy” and Bill Murray in “What About Bob?”, Korsmo sported an enormous confidence that still lingers in the mind of his co-star, Caroline Goodall, who played his devoted mother, Moira.

“I remember the scene on the plane where Charlie and Robin were just riffing,” said Goodall. “In every moment, Charlie was on top of it, and Steven adored him because I think he reminded him of himself a bit. We knew that he was doing college-level math and he was only 12. It’s hard to improv Robin out of an improv, and Charlie had no problem doing that! No matter what Robin would say, Charlie would have a response for him, which created a very real father/son dynamic between them. As an actor, you always have to be able to step back and know exactly what, in a way, the shape of the improv is, and Charlie had that ability at such a young age. He also had a gift for physical comedy, which you see on the doorstep where he chokes on the gum. He was just an absolute joy, and a bit scary at times because he’d come straight back at you with a one-liner, and you were floored. He was too smart for words.”

Unlike Hoffman and Jessica Lange, the latter of whom starred in his 1990 debut film, “Men Don’t Leave,” Korsmo was not a Method actor, and delivered authentic work because of his uncommon ability to be fully present within a scene. It is the reason why his palpable delight, perhaps most memorably observed in the scene where Hook smashes a roomful of clocks, is so infectious. He recalls the experience of making “Hook” as being more improvisational than his previous work, particularly the scenes that didn’t involve special effects.

“When we shot the scenes on the pirate ship in Neverland, the opportunity to improvise went down drastically,” said Korsmo, “but when you are doing a scene like the one on the plane, they would just let the camera run and allow us to try lines different ways while bouncing off each other. The moment where I bang my baseball on the window was the sort of thing we tried probably a half-dozen ways to see how it could be funny. It’s frankly a good thing that I did this work at a young enough age where I wasn’t intimidated by people or didn’t feel that my career depended on anything. I never really expected that my career would last. It was just a fun way to get out of school. My family wasn’t depending on me to pay the mortgage or anything, which took the pressure off. Plus Steven was very respectful of his actors as being part of the creative team. He told you what he was looking for while noting, ‘You’re a better actor than I am, so do with it what you will.’”

James confesses that he still melts every time Granny Wendy (the incomparable Maggie Smith) first appears in shadow at the top of the stairs, welcoming Peter to her home with the line, “Hello boy.” The stories she shares with Maggie about how J.M. Barrie would visit her family enabled James to pay homage to the Llewelyn Davies family, with whom the author first shared his Pan stories. Smith radiates maternal warmth when greeting her family with the line, “Give us a squdge,” while the age makeup by Greg Cannom (who later won an Oscar for “Bram Stoker’s Dracula”) is so convincing, it’s impossible to believe that the actress was only in her mid-50s at the time.

My personal favorite scene in all of “Hook” is the monologue delivered by Moira in which she quietly yet firmly tells Peter, “You’re missing it.” Though there have been countless imitations of this scenario, in which a self-involved parent is forcibly removed from his cell phone, none have articulated the essence of its message with the grace of this sublime moment, which is wisely not accompanied by a score. Though the scene was not in the draft that Spielberg had committed to, the director’s dissatisfaction with the character of Moira caused James to have him read a scene from his long-discarded first draft where the character challenges Peter by saying, “Your children don’t need a policeman, they need you to play with them.”

This dialogue was rewritten in part by Malia Scotch Marmo, on the heels of penning Hallström’s endearing gem, “Once Around,” who was originally brought onto the project by Hoffman to write for him. When James asked Kathleen Kennedy if he could meet Scotch Marmo in order to remove any awkwardness from their working relationship, the writer showed up at his apartment dressed like a fairy with a green tunic, leotard and elfin shoes, not to mention the sassy spirit of Peter’s infatuated companion, Tinkerbell. James cites Scotch Marmo as an invaluable ally who fought to preserve the original script while contributing enormously to it (for example, the aforementioned line, “Hello boy,” was penned by her), enough to earn her co-writing credit.

Scotch Marmo spoke with me via email for this piece, and recalled receiving the “Hook” screenplay in the mail from Hoffman, along with a request that she check out his character. She sent him back some notes and quickly forgot about it. Two weeks later, Scotch Marmo had been “flying” her three-year-old around her head at her apartment in Hoboken while singing “You Can Fly,” when the phone rang. It was Hoffman.

“He told me he shared the pages that I had rewritten with Steven,” said Scotch Marmo. “And I recall saying, ‘I didn’t ask you to share pages. I thought that was between you and me,’ and he said, ‘Yes, but nonetheless, I have Steven Spielberg here.’ I just found it odd that he would share something personal. Eventually I learned that in Hollywood, nothing is personal. Everything is pinned up on the community board. But in any case, Steven was totally enjoyable to talk to. There was an instant, simple rapport. I could sense he was a good, decent person right away, as well as someone who was in love with Peter Pan. After we spoke for a few minutes, he asked if I could write like I speak, and I said, ‘Definitely, I can do better. I do much better writing than speaking.’ He asked if I would do a few more scenes, and I said, ‘Yes, I’d like to not get agents involved because I just want to fill out the character.’ And he agreed. I don’t know if that could happen today.”

<span id=”selection-marker-1″ class=”redactor-selection-marker”></span>

Once Spielberg formally brought Scotch Marmo onto the project, the agents did get involved, and Spielberg asked her to restructure the film many different ways, while rewriting preexisting scenes as well as creating new ones. According to Scotch Marmo, it was Spielberg who called her saying that he wanted her to meet James personally so that they could build a relationship. It also happened to be a Writer’s Guild requirement that very few directors in Scotch Marmo’s experience have honored. She leapt at the opportunity and vividly remembers her meeting with James at his apartment.

“There were drawings of Peter Pan all over the house because both of us had young children,” recalled Scotch Marmo. “Jim and I were both strangely, perhaps overly in love with Peter Pan because we have had the many versions of Barrie’s story grafted on our souls. So it’s hard to explain what that does when you meet someone who is so in line with the story of the little boy who didn’t want to grow up. I also admired Jim’s original screenplay very much. It went through many, many changes. His first version was darker, but I would say we both worked out of a profound love of the Barrie story. We worked from that base. So it was like two Peter Pan apostles talking about Barrie—not to be sacrilegious—and Jim was like a font of intellectual thoughts about how the story was unfolding and its meaning. I was more concerned with constructing scenes around those subtexts that he was creating.”

While Scotch Marmo valued James’ ability to connect with Barrie and the multitude of Peter Pan adaptations, Spielberg utilized her ability to “keep an eye on the unfolding structure on a very unwieldy creative set.” It was through her collaboration with James that Moira’s monologue proved to be an unforgettable showcase for Goodall.

“You know instinctively, as an actor, that this is your lodestar scene, and if you don’t get it right, you are in trouble,” said Goodall. “It also serves as a pivotal turning point that leads to the beginning of act two with the arrival of Tinkerbell. As a writer, Jim understands structure and the fusion of character and dialogue so perfectly. He can encapsulate it so that the actor can then pick up the ball and make it real for themselves so that you don’t, as the audience, feel that you are being moved on to the next chapter. That particular scene was a night shoot scheduled after our work with the kids. In the scene where Robin yells at them to leave the room, Charlie Korsmo and Amber Scott were unbelievable and truly frightened as well, which gave us the impetus for our next scene. Jim set it up with the comedy of me doing something very out of character—which is the best way to have a character—by chucking the phone out the window. It completely stops Peter as a human being, and when Moira says, ‘I hated the deal,’ you get an understanding of who she is. She’s mom, she has played backup and she has put up with his absences because she loves him, but this is the moment where she says, ‘That’s it.’

It’s really nice for an actor to have that sense of certainty in themselves about what it is they feel and who they are. Then Steven placed us in that window seat, so there was no room for us to move. We had to sort of confront each other, and he did one of those camera moves which, ironically, if you look at ‘Schindler’s List,’ he did the other way with me and Liam Neeson. He starts by focusing on one person, and he moves across, camera right, but so slowly that you have no idea what he’s doing until you actually end up on the other person’s face. I remember one thing Steven always used to say was, ‘Motion picture,’ and what he meant by that was that the camera—his camera—is always moving in order to tell the story. There’s an extraordinary kind of alchemy that happens where the audience doesn’t quite understand why they’re suddenly laughing or crying. You are having an emotional moment because the camera is taking you there as much as the actor is. We can sometimes get very depressed as actors if the shooting of a scene is not supporting where we are emotionally, because the audience won’t be engaging in it in the same way, but Steven has a genius in knowing how to do that.”

The monologue was actually written to be longer, and Goodall didn’t feel that she was in a position to fight for James’ words, since “Hook” was her first big movie. As often happened on the set, Hoffman was present for the shooting of this scene, despite the fact he wasn’t in it. Scotch Marmo cites the rehearsal of this scene as having one of the most memorable writing moments of her career. Though she describes their working relationship as an otherwise “phenomenally good” one, that evening Hoffman said, “The camera’s working at 100%, the actors are working at 100%,” and then—Scotch Marmo recalls, “almost like Hook himself”—he swung around and pointed at her, saying, “It’s only her. She’s not working at 100%!”

“Steven is terrifically empathic and he said, ‘let’s all take a break,’” remembers Scotch Marmo. “I kept composed and went to Steven’s trailer. I can’t explain why it was such an out-of-body experience for me to be called out like that, but it was. For some reason, it seemed to go deeper than the words and I was unable to process them. At the same time, I definitely had to get past my own feelings and dig deeper. There was a knock on the door of the trailer, which was odd because usually Steven would just come in. I opened it, and it was Robin Williams. He sat down across from me and just stared down at the ground, creating a peaceful atmosphere. He could see I was deeply troubled. After about a five-minute silence, he told me the strengths of the scene and asked if we could just walk through it, and we did.

He asked to talk about the phenomenon where men were working really hard, during the age of greed, to prove their business powers, and leaving their families behind. I had experience with that. It was everywhere. We talked about it and it really influenced the scene immensely. I wrote out some things with Robin present and passed it to him. He wrote a little bit himself and passed it back and he got up and left me to the work. Having Robin’s trust was essential to my getting to the heart of that scene. I brought the scene to Bonnie Curtis, who was Steven Spielberg’s superb assistant, and she had it typed and brought to the set. They worked on it and it hit the mark for everyone the next day. At dailies, a number of crew members just touched my shoulder and said the scene was very good. Dustin’s intrusion on this scene did help bring it to life, but without Robin and Steven’s sincere empathy and desire for me to find that scene, I don’t know if it could have worked.”

On the set, a conversation had transpired between Hoffman, Williams, Spielberg and Goodall that proved to have a profound impact on the scene itself, perhaps setting the mood for Williams’ meeting with Scotch Marmo.

“Here were these three men from quite different walks of life all of a sudden congregating in the same place with little old me as a sort of moderator,” recalled Goodall. “We started talking about what Jim was really writing about in the scene, which is, ‘What does it mean to be a man and a father?’ I had a strange kind of courage in asking them this, which only the intimacy of shooting a scene like that can give you. I asked, ‘Why are you guys doing this film? Do you feel like you’re Peter Pan in some way?’ And every single one of them replied with their own story. They were so open about the fact that they had choices to make about who they were as artists, as men, as husbands and fathers, and that is why they were drawn to the film so very deeply.

They all shared interesting stories about why they went into the business in the first place, and their feelings that they’ve never accomplished enough. I think that’s how we got into the mood we needed for the scene because everything suddenly got kind of inward, and you know as an actor that you’re in a truthful place. Robin wanted to get into that place and root it there because he knew that there was going to be a lot of hijinks and antics coming up. I still feel emotional when I think about that scene, and I think that’s why it comes across as emotional when people watch it.”

“A lot of what you see on camera came out of that meeting,” agreed James. “Caroline was dealing with three fortysomething men who, like me, were really questioning where they were in their life—as artists, as fathers, as capitalists, as egomaniacs—and that scene really personalized everything that I hoped Robin would find in the role. He got serious, and when he’s screaming at the kids, it shouldn’t be like a feel good movie on the Hallmark channel. It had to be just as raw and powerful as the scenes that Steven did with Ricky Dreyfuss in ‘Close Encounters.’”

“Robin was not a wild and crazy guy in real life,” said Korsmo. “He was very intelligent, kind of quiet, humble and almost self-conscious. He always felt like he had a lot to live up to in terms of his reputation for being the life of the party. I could feel the pressure and insecurity that was around him even as a kid. He was the complete opposite of someone who felt he was above people. He was really a gentle soul. I think both he and Dustin had very ambivalent attitudes towards being famous at that point. It obviously has its upsides, but it also is very isolating and limiting, and I don’t think either one of them really enjoyed it. I remember going to Taco Bell on a lunch break and Robin saying, ‘I wish I could go there,’ and he wasn’t kidding. He couldn’t walk into a Taco Bell without it becoming a scene, so I had to bring him back some tacos.”

James vividly recalls how Smith would impeccably play her symphony of emotions during each take of the charity dinner held in Wendy’s honor at the Great Ormond Street Hospital, where she gave an individual gesture to each of the orphans who saluted her. It was Scotch Marmo’s idea to have Peter stumble over the word “effortlessly” in his speech, while Carrie Fisher—who was brought on as an uncredited script doctor, primarily to rewrite Tinkerbell’s dialogue—wrote the rat joke that elicits laughter from the crowd, according to James.

“We were on set and Maggie couldn’t produce the requisite tears for a pivotal scene with the full crew around and the cameras rolling,” said Scotch Marmo. “Dustin Hoffman stepped forward and started to talk to Maggie about a private memory. He never mentioned what it was, but he mentioned that there was a private memory she had shared with him, and he said, ‘Can you reach in and get that?’ And what was amazing about it was Steven Spielberg’s complete confidence in himself as a director to allow an actor to step forward without asking, speak to the actor and get from her what was necessary. I had never seen a director allow a cast to interact so freely with each other to get the best possible performances he could get. He was in charge at that moment by letting go of the reins, and it was just wonderful to see his confidence. And Maggie brought the scene to life.”

Peter’s touching speech is juxtaposed with the terrifying set piece where Jack and Maggie are snatched from their beds by sinister unseen forces that leave behind the unmistakable scratch mark of a hook, leading up to a note signed by the captain and pinned on the bedroom door with a dagger. It’s the sort of prologue that Spielberg excels at, masterfully building suspense and anticipation for the second act while taking the time to develop the characters so that our emotions are engaged.

“The London section had the most important writing I did for the film, and the studio kept trying to get me to cut stuff out of it so that we could hurry and get to Neverland,” said James. “They said, ‘We want to be in Neverland by page 10,’ and I replied, ‘Well, first of all, it’s not your call, it’s Mr. Spielberg’s. And second, if you don’t set up those characters right in London, it doesn’t matter what happens in Neverland, and I do think that’s where the movie got lost.”

Though the Neverland scenes are undoubtedly a mixed bag, the filming of them during the middle of 1991 provided Jake Hart with the best summer of his life. It was the only time he bothered to keep a diary with which to chronicle the extended studio shoot, where the crew wore shirts displaying a hook with the number 100 nested inside when it hit 100 days. He recalls watching the MGM sign being lifted out and the Sony sign being dropped down after the studio had acquired the historic complex. The family atmosphere onset was exemplified by how Spielberg would allow Jake to watch scenes over his shoulder on the monitors, while seated in his own director’s chair. He also was granted the opportunity to attend dailies, which many executives weren’t allowed to do. Jake was even present during the scoring sessions of John Williams’ awe-inspiring music, which cumulatively builds to the moment when Peter soars into the air, a la E.T.

“Words can’t describe how lucky I am to have had that experience with that group of people at that moment in time,” said Jake. “I was raised on the films of Errol Flynn, and at lunch, when the fight choreographers would take Robin and Dustin’s stunt doubles to train for the fight, I would eat lunch in the commissary very fast so that I could hide around the corner and watch them train every day. Of course, they saw me, and the fight leader came over one day and said, ‘Look, if you’re going to spy on us, you might as well learn something.’ So they would train me while they were training Robin. Then when it came time to shoot the war, they realized they needed fifteen kids who could fight, and since I knew the entire system, they hired me to be in the background of a lot of the battle scenes, which were shot over two weeks.

My fight partner was a pirate called Big Stu—he was 6’ 4’’ and I was 4’ 9’’—and we would come up with fights. The tightest relationship I had was with two background pirates. The first time they saw me when I was dressed for the war, they started calling me the Bobby Brady pirate because of my poofy dome hair. Every time I saw those guys, they would invite me over and we’d just talk and laugh. It was one of the first experiences where I saw that you could kid around with people and make fun of each other. When they shot a Coca Cola commercial on the pirate town set, those were the two guys they chose to be in it because everybody loved them.”

During my Zoom session with James, he held up a cherished gift he had received from the props department and Bob Hoskins, who portrayed Hook’s goofy counterpart Smee in the film. It was one of the three swords Williams used in the film, comprised of bronzed metal, coconut and a cork handle wrapped in fabric.

“My kids learned so much about set decorum, discipline and protocol by watching Robin Williams,” said James. “Robin didn’t have an entourage. He didn’t have twenty people come up to him after a take and take care of him the way Dustin did. He hung around the set all the time like a crew guy. Every day he’d see Jake, he’d bow to him and say, ‘Thank you for my job!’ This is how Jake learned that writers are job creators. Nobody has a job until a writer types ‘the end.’ Jake and Julia got to see how you are supposed to behave on a set, and the respect you show the actors and crew members. When Julia makes a film, she knows everybody’s name on the crew along with what they do, and she learned that on the ‘Hook’ set.”

Apart from appearing in an early Tom Hanks picture, 1986’s “Every Time We Say Goodbye,” as well as a slew of television productions, Goodall’s acting experience had primarily been on the stage prior to filming “Hook,” and she was struck by the incredible commitment everyone had to the picture. She vividly recalls the egalitarian nature of Willams, who would turn to Steven after each take and ask, “Is that alright, boss?”, which eventually prompted her to do the same.

“I had the constant feeling of being enveloped in love and a sense of welcome on that set, where you were encouraged to be there or be square,” recalled Caroline. “Who wouldn’t want to be on the ‘Hook’ set every single goddamn day? Apart from it being the best master class in the world for an aspiring filmmaker such as myself, it also was so much fun. We were all given crew badges around our necks that were decorated Lost Boys-style with beads and Tinkerbell feathers. They would serve as our entry to five sound studios that we could visit, one of them being where ‘The Wizard of Oz’ was shot. I became the unofficial guide for visitors who had heard about how wonderful the sets were, so occasionally I’d get requests like, ‘Hey, Caroline, could you take Jon Voight around? He’s just popped down with his daughter.’”

So heightened was the curiosity around Hollywood regarding “Hook” that a guest book was kept to log the numerous visitors to the set, from Kevin Costner to Prince. Some major celebrities made it into the film in bit parts, such as Phil Collins as the inspector in London, George Lucas and Carrie Fisher as a couple kissing on a bridge, Gwyneth Paltrow as young Wendy and most astonishingly, Glenn Close, who is so brilliantly disguised as the ill-fated pirate Gutless that she is utterly unrecognizable.

“One of the most amazing moments of my life occurred when we first saw David Crosby of Crosby, Stills & Nash walking across the set,” said Jake. “My mom freaked out and introduced herself to Crosby, who was cast as a pirate. He said, ‘Oh my god, you’re Jim Hart’s wife? Where is he? I want to talk to him! I love the script.’ So my mom went to find dad and left me with David Crosby. I went into his trailer, and I listened to him make some phone calls. He was calling everybody he knew saying, ‘Hey man, it’s my fiftieth birthday. You know, the one where your dick falls off. You should come to my party.’ And that was how we met. David and his wife Jan were effectively my godparents after that. The way our family grew as a result of that summer was remarkable.”

Occasionally, some of Williams’ improvised lines onset would give away something that was coming up in the script, which Scotch Marmo made sure to inform Spielberg about in order to “steady the ship.” Though she dubs the set as being “incredibly male,” with its squadron of pirates hanging around, she doesn’t recall having negative experiences there—for the most part.

“The crew was also almost all men, as I recall,” said Scotch Marmo. “There were days that I felt that Kathy Kennedy and I were the only women there. For the most part, it was a very un-sexist set. The one or two times it was not, I handled it well. The one time there was some bad form, I slew that man like a pirate would.”

Though Basco now believes that the film’s multi-cultural ensemble of Lost Boys, who came to Neverland from different eras as evidenced by their attire, as a refreshing example of onscreen representation, this topic couldn’t have been further from his mind during filming.

“I was 15 when I did the film, and at that age, you’re not really understanding ethnicity or identity,” said Dante. “That comes later in high school. When kids go to college, they are out there by themselves for the first time, and that is when their identities start to get locked in. My biggest note from Spielberg, which he wrote on my script, was, ‘Stop imitating Brando, Basco is an original.’ I’d be acting in a scene and he’d be like, ‘Cut—stop imitating Brando! Back to the top.’ I was really doing Pacino, who was probably doing Brando—that’s the lineage of stuff we were studying. Even in my early conversations with Steven, I was talking about Hoffman as Ratso Rizzo in ‘Midnight Cowboy.’ As Rufio, I would like to think that I just did really good work as a young actor, and that helped me transcend the character.”

A memorable encounter with Spielberg occurred when Basco asked him what the budget was for the increasingly expensive production. “He looked at me and went, ‘Okay, think of a number. Now double it—we’re over that number,’” laughed Basco. As rewrites continued during the shoot, Scotch Marmo was instrumental in elevating the presence of Hook, whom James had originally envisioned as being played by Daniel Day-Lewis. When Hoffman was cast, the general feeling from the Hart family was that he was too short to play the fearsome captain. For the moment during the climactic duel when Peter mentions that he remembers Hook being taller, Julia came up with the line, “To a 10-year-old, I’m huge,” which wound up in the film. One thing that nearly didn’t make the final cut, however, was the demise of Rufio.

“Steven had cut Rufio’s death out of the film, and I kept trying to explain to him and Kathleen Kennedy that his death was important because it shows that people can die in Neverland,” said James. “Without that death, there is no jeopardy—they are just throwing tomatoes at each other. Finally, one day, I was working on ‘Dracula’ in my little teeny office when Robin’s stunt double Keith Campbell stuck his head through the door. He said, ‘We’re gonna kill Rufio,’ and I went, ‘Yes!’ I never learned how or why Steven made that decision to put it back, but it’s still one of the most poignant and impactful moments that kids experience at a young age.”

“I think Rufio’s death kind of immortalized the character in that Dean-ish way,” reflected Basco. “The fact it kind of traumatized people is what helped the character stick around so long to a degree. Once I found out that Rufio’s death was finally scheduled to be shot, as a young actor who was very serious about my craft, I wanted to talk with my elder statesman actors about how I would approach my first death scene. I knocked on some of their trailer doors to get their advice, and Bob Hoskins was like, ‘Well, you stop breathin’ right?’ I had been following Dustin around like a puppy dog through the whole shoot because he was one of those ’70s character actors—like Pacino, De Niro and Nicholson—who really changed the landscape of what Hollywood would become.

I was watching Hoffman films every night—‘The Graduate,’ ‘Kramer Vs. Kramer,’ ‘Lenny’—and I’d be coming to the set on my days off to watch him work and ask him about his career. I was kind of a pain in his ass, but when it came to me asking him about the death scene, he told me that he would be there for the filming of it. He ended up walking me through it and really validating me as an acting coach would during the shoot. It was one of those surreal moments where my hero got to be my mentor. I often tell other artists, ‘When you are in the presence of greatness—you need to have the wherewithal to sit there and listen and take it in.’ Working with these guys is equivalent to sitting in a room and watching Picasso paint a brushstroke, or being in a concert hall and seeing Mozart conduct a symphony.”

One person from the “Hook” set who looms large in the memories of both James and Jake is Hoskins, who became like family to the Hart clan.

“Bob was one of this film’s unsung heroes,” said James. “We became great mates. Like all the Brits, Bob Hoskins would show up prepared. He knew his lines, he knew everybody else’s lines, he knew the scene that was being shot, and he usually knew more about the setup than even the director. Bob became a kind of guide for Dustin, and tried to keep him on track. I remember one day, Bob had to go to Dustin and say, ‘Listen, we’re not a couple of nelly queens in vaudeville, we’re pirates! We steal children.’ He was so good for Steven because he was like Robin in that he would do anything—he would do multiple takes and change the scene if it needed a change. If you watch him and Robin in the film, they are some kind of glue and anchor that is the reason each of their scenes work.”

“My father is an Italian immigrant, a nuclear physicist, and an incredibly passionate man,” said Scotch Marmo. “My mother is a housewife and crazy in love with my father. I cast them as Hook and Smee, and I know their voices so well since, you know, prenatally. So I landed on that relationship of husband and wife and those personalities of an extremely passionate, dramatic person and a caring, loving partner who’s not scared of all that energy and passion, and just likes it. So I added that dimension. Also, I was raising children and they were little, and I was staying up all night. I was riding my convertible around Manhattan in the wee hours, and I was going to clubs and eating dinner at 6am at a diner in the East Village.

So I knew when Hook was going to go after the children, he could tell them a horrible truth about adults that would ring true with parents whether they like it or not, particularly those who lived an extraordinary single life. I was in New York City, where I got to spend late nights with friends at small clubs and gallery openings. My father gave me an old 1980s gorgeous cream cup convertible that I drove all over the city. It was just great. So I felt the domestication that comes with children acutely. I totally loved it, but there’s a flip side to ‘missing it.’ I could look over my shoulder at a more wild life, one without clocks, and many dinners at dawn in Manhattan. Also, Manhattan was a rougher place, so in my estimation, it was more fun than it is today.”

The day that Francis Ford Coppola, whose next picture was “Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” visited the set with his granddaughter—another future filmmaker, Gia—Hoffman and Hoskins were in the midst of shooting Hook’s failed attempt at suicide, which is comical while also conveying his underlying pain. Hoffman began blowing his lines to such an extent, Coppola leaned over to James and said, “I think I’m making Dustin nervous,” and excused himself after the next take. At the end of the day, Hoffman tracked down James to ask, “What did Mr. Coppola think? Did I do okay?”, to which he replied, “Dustin, you were perfect.”

“I’m always blown away when I hear actors who have achieved so much success—Oscars and everything else—still being worried about their next job,” said Goodall. “Larry Olivier apparently always worried about whether he was ever going to work again. It doesn’t matter who you are or what you’ve managed to achieve. There is always going to be the little person inside that says you’re not good enough. Even after achieving an enormous amount of success, people still spend their lives desperately trying to prove that they are good enough, even if it is only to themselves. I think that’s why people are great artists, because otherwise, they wouldn’t keep striving. I remember a very fine director Peter Gill at the National Theatre in London telling me that he could never impress his mother.

Another time, I was sitting next to Sting at dinner, and he told me how his father, who was a milkman, never congratulated him for being a musician, let alone a superstar. On his deathbed, his father looked at him and just basically said, ‘Yeah, your hands are quite like mine.’ I think we’re all searching for approval or some kind of inner knowledge that we’re okay. That night I spoke with Steven, Robin and Dustin, they each came up with a terribly personal story about their sense or lack of self-esteem. A real artist just aspires to be better and better whatever it is they do because they know that there is always something ephemeral that they will never be able to reach, and those damn goal posts are always going to be moving.”

James’ script is chock full of subtle homages to Barrie’s text, such as when Hook says, “Strike now, Peter. Strike true,” echoing the words of the lost boy Tootles after he realizes he has mistakenly shot down Wendy. It was Spielberg who found what would become Peter’s last line in the film, which was included in the author’s notes of Barrie’s play: “To live will be an awfully big adventure,” which provides a fresh spin on one of the titular hero’s most famous lines. The script also succeeds in capturing the essence of Barrie’s ageless 110-year-old novel, such as its description of Mrs. Darling upon seeing her children finally nestled back in their beds after their adventure in Neverland…

The children waited for her cry of joy, but it did not come. She saw them, but she did not believe they were there. You see, she saw them in their beds so often in her dreams that she thought this was just the dream hanging around her still.

This is precisely how Moira reacts to the sudden return of her children during the euphoric finale of “Hook,” and it is another moment that Goodall plays to perfection, as her melancholy trance is suddenly ruptured by turbulent emotion.

“We’d had this whole hilarious rigamarole with a leaf landing the wrong way on my shoulder,” said Goodall. “In those days, you couldn’t CGI it, so we had a very heavy footed props guy trying to land a leaf that hung on the end of a fishing pole. I found it hard to muster the needed emotion when Moira’s children returned, since I knew that they were standing around the corner waiting for their cue. Dustin was on set, and he told me, ‘When you get to your knees, don’t hug them immediately. Push them away from you and look at them, in their faces, and then embrace them.’ That gave us the moment for that mutual emotion to happen, and the recognition of everything that went on. That’s how I was able to get the real tears to come out.”

It’s as arresting as the flashback from earlier in the film where Peter remembers why he chose to grow up—he wanted to become a father. This is the scene that made me cry while revisiting the film in the days following Williams’ death in 2014, since it potently reflected the happy thoughts we all strive to remember during times of adversity. Goodall is only on screen for a few seconds, and yet the radiance of her joy lingers long afterward.

“I had not had kids when I shot the scene, and I think what’s really funny is the best time I ever played a mother was when I wasn’t one,” laughed Goodall. “After having kids myself, I simply felt like I had already been through the things I was portraying onscreen. Also, getting to act with a real baby on ‘Hook’ was highly preferable to my experience on ‘The Princess Diaries 2,’ where I had to hide a bloody doll through the whole movie. Garry Marshall was like, ‘Just carry the doll, it’s fine!’, but it just wasn’t the same.”

A character who I clearly remember earning laughs in the theater when I first saw “Hook” at age 5 was Tootles, wonderfully played by Arthur Malet, who we see in the earlier scenes crawling along the floor of Wendy’s house. When Peter asks what he’s looking for, Tootles responds, “I’ve lost my marbles.”

“Robin had felt that Tootles was the soul of the story,” said James. “I put my brother in everything I do. We lost him very early in life, and he was Tootles in this one, so when they cut the character out, I was devastated. Then I heard that when Robin read the script and saw that Tootles was cut out, he threw the script against the wall. It was probably Robin who got Steven to put Tootles back in the script.”

It was only recently that I realized Malet had played the son of Mr. Dawes (Dick Van Dyke) in “Mary Poppins,” who cries, “Father, come down!”, as his dad flies into the air when overtaken by a bout of laughter. Tootles does the same thing when Peter surprises him with his lost bag of marbles at the end of “Hook,” thus creating an homage that ingeniously connects the similar character arcs of George Banks—the stuffy father in “Poppins”—and Peter Banning. Neither James nor Jake were aware of this connection when I mentioned it to them (“I cannot tell you how happy I am to know that this is the reality we live in,” Jake gushed upon hearing it), while Goodall agrees that this could not have been a coincidence.

“I was aware Arthur was in ‘Mary Poppins’ because it is one of my favorite films,” said Caroline. “It was the first film I ever saw, and later on I was fortunate enough to work with Julie Andrews. There were not many Brits on the set, so when Arthur and I had a little down time, I’d speak to him about how he came to America. He was a wonderful, brilliant character actor who had been in a string of Ealing comedies and had worked with my parents’ great friend, Ken Annakin. I was just fascinated by him and his humility. He loved every minute of it, and Steven really loved him too. He’s a bit of an unsung hero in that he came in for a small role and he bloody nailed it. In a way, Tootles is the lynchpin of the story in that he serves as a crossover, handing the baton between J.M. Barrie’s book, where he is Peter’s best friend, and this new version.

Steven had an encyclopedic knowledge of films, and his wife Kate used to say, ‘You can’t get him off the telly either.’ He’d sit there clicking through stuff, and he’s one of the few directors who would cast off of the television. He’d see someone on screen and ask, ‘Can you find out about that person?’ He’s like Tarantino in that way. I remember auditioning for a role that was cut out of ‘Kill Bill.’ I walked in and Quentin said, ‘Oh wow—you worked with one of my favorite directors!’ It was a lovely Australian filmmaker, Richard Franklin, who had directed ‘Psycho II.’ Quentin had liked a film he had previously done with me, and I was blown away that he knew who that guy was. It came in from left field. So I’m absolutely convinced that Steven had a particular reason for casting Arthur Malet.”

It was of great importance to James that the Great Ormond Street Hospital would have a role in the film, since it was the place to which Barrie donated the copyright to Peter Pan in 1929, bequeathing the rights to its characters. While the stage plays and musicals were diligent about paying royalties, James learned that the hospital wasn’t very forceful about enforcing the copyright laws, reportedly resulting in Disney paying a meager $5,000 for the rights until they were guilted into a larger settlement many years later. After conducting his research on this, James urged the head of business affairs at Sony to make good by the hospital, and to their credit, they agreed to have the royal premiere in London, while paying 500,000 pounds to the hospital.

“We were all in London for the royal premiere on Julia’s tenth birthday,” said James. “Part of the celebration was to go tour the hospital, which is where parents can actually live in the room with their child. When we visited, there were injured kids who were brought in from the bombings in Eastern Europe. It’s an extraordinary place. There was a corridor upon which a Peter Pan mural had been painted by a well-to-do artist whose child was saved at the hospital. When we arrived with Robin and Dustin at this corridor, it was jam-packed with kids in wheelchairs, on gurneys, on crutches and their nurses, all waiting to see Captain Hook and Peter Pan.

I watched Robin take Julia and Jake through this maze of people, and I could see their lives changing right before my eyes. That night, we had the royal premiere where they got to meet Princess Diana and the boys. After the celebration was over, Julia came into our bedroom and announced that she had made a decision about her life. She decided that next year, she would like to raise money for the Great Ormond Street Hospital instead of getting birthday presents. That started our charity, the Peter Pan Children’s Fund, which celebrates children’s birthdays by providing them with money for their local children’s hospital.”

“Hook” had its official premiere in Hollywood on December 8th, 1991, before having its London premiere the following April. Though it grossed $300 million worldwide, its $70 million budget caused the much-hyped blockbuster to fall below the industry’s lofty box office expectations. The film was nominated for five Oscars—Best Art Direction, Best Costume Design, Best Makeup, Best Original Song and Best Visual Effects—but it received an onslaught of negative reviews from prominent film critics, including this site’s own namesake, Roger Ebert, who complained that the look of Neverland didn’t correlate with the one that existed in his mind. “The whole thing looks like what it is, a movie set, right down to the unconvincing backdrops, and for some reason, there’s a shift to red and brown in the color spectrum, so Neverland (which in my imagination, at least, is on a lush green island) looks as if it’s in the midst of a drought,” he wrote.

Ebert’s longtime sparring partner, Gene Siskel, shared his sentiment, dubbing Spielberg’s depiction of Neverland a “tiresome bore” that failed to pay off on the promise of the opening sequences, which he felt were marvelous. During their review of “Hook” on “Siskel & Ebert” (which can be viewed at the 10:53 mark in the video embedded below), the critics lamented that Spielberg hadn’t followed through on his original plan to make the film a musical. Indeed, seven songs were written by John Williams and Leslie Bricusse, though only two of them made it into the film, including the Oscar-nominated “When You’re Alone,” sung by Maggie on Hook’s ship. According to Goodall, the sequence was originally going to cut back to London, where she and Maggie Smith each sang a verse of the song (she recalls Smith fretting, “Darling, I can’t sing!”). James notes that if you look closely at the mouths of the pirates as they chant “Hook! Hook!”, they are clearly performing different lyrics to a song that had been cut. Both he and Jake felt that the songs were incongruous with the tone of the script, and were relieved to see them cut.

In a 2018 interview with Empire magazine, Spielberg admitted that he felt like a fish out of water while making “Hook,” saying, “I didn’t have confidence in the script. I had confidence in the first act and I had confidence in the epilogue. I didn’t have confidence in the body of it.” He felt that his insecurity caused him to focus more on production value during the Neverland scenes, which is precisely what disappointed many viewers—and not just the critics.

“The first time I saw the film at a screening where it was just our family, I was 12 years old at the time, and I couldn’t talk to dad for two weeks,” said Jake. “I was so upset because I had read all the scripts, I had been at all the conversations with him, I knew what it was supposed to be, and you’re not going to have a great script if you keep hiring writers to tweak things because you don’t know what you want. Of course, that was my perspective as a kid who had no idea what it takes to make a movie. I don’t mind that Steven doesn’t like the movie. I love what the movie is and what it represents. But as a piece of cinema, for my money, he blew it.”

Though Spielberg’s words can be interpreted more than one way, my own feeling is that he is blaming himself for not having enough confidence in the script, and being uncertain about how to do it justice. James feels that part of the problem had to do with Spielberg being trapped into a December release date, resulting in limited time for him to stick the landing. At one point, the acclaimed playwright Tom Stoppard came in to write a scene, and he sent James a letter thanking him “for letting me put my oar in your water.” Scotch Marmo remembers how Spielberg would come to the trailer with an accordion folder containing numerous drafts written by various people of the scenes they would be shooting that day. She would then find a way to lace them together. Though Spielberg appears to have welcomed Hoffman’s involvement in various aspects of the production, Goodall does recall hearing the director grumble during an ADR session, “I feel like locking Dustin out of the editing suite.”

“It was Sony Studios’ first flagship film, so it was important for the studio to have Steven Spielberg direct their first film,” said Goodall. “Steven wasn’t at Universal, which was always his spiritual as well as physical home. I could see some stresses and strains that were coming from the outside, from the studio, and impacting the film. There was so much money going into it that it had to appeal to everybody around the world. So you had people scratching their heads saying, ‘Well, a child can’t die because then we can’t sell it to certain places.’ In those days, Americans did not like accents and they certainly weren’t reading subtitles like they are now.

It also coincided with the growing of the international market. Eastern Europe had just fallen, and suddenly you had hundreds of millions of new potential viewers and a market there. All of those things were building into the ramifications of making a film that has Steven Spielberg’s name on it. I remember on day one, the marketing people were on set, and this guy came up to me and said, ‘I’m doing your doll.’ Sony had done the deals already for the marketing—all sorts of toys and coloring books and god knows what else—before we had even made the movie!”

Among the major elements that were cut from James’ script included Tiger Lily and her indigenous tribe. When asked by Kathleen Kennedy, “Why do we need the Indians?”, Judy reportedly answered, “Because they were there first.” The climactic fight between Pan and Hook was originally written to take place on the ship at sea, a set piece that Jake noted was later realized in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” films. Amidst these creative differences, James had to learn to be a “facilitator and fixer as opposed to a whiner,” though he was further let down when Fisher—who he used as a muse for Tinkerbell (played in the film by Julia Roberts)—took some of the edge out of the character, turning her into more of a cheerleader. Jake also felt that the film never delivered on the menace so skillfully set up in the first act, and holds high hopes that David Lowery’s “Peter Pan & Wendy,” which is due for release next year, will serve as a corrective to this missed opportunity.

“When Peter Pan and Captain Hook were shooting the sword fight, they were just riffing ideas,” recalled Jake. “At one point, they went into a bar in the pirate town set, and a fight was choreographed in which they found flagons of beer on a table and drank while fighting without looking. It was incredible to watch, but it was the type of thing that had no place in the movie. This was a fight to the death between the most legendary enemies in literature, and they were doing a circus act. ‘Hook’ is a story about a guy who needs to risk his life to save the kids he was ignoring because he didn’t know how to deal with his own lost childhood. I don’t feel any of that in the Neverland scenes past what Robin is giving you. Dustin and Bob are wonderful together as Hook and Smee, but that is not a Captain Hook I think even a kid could be afraid of. He’s just so delightful, and Bob is right there with him, being the clown that he was trained to be. He once demonstrated onset how he could spit fire.”

On the set, Korsmo once asked Spielberg what he thought was his worst film, and the director replied that he liked all of his films, including “1941,” which stands in contrast to how he speaks of “Hook.” When he attended the premiere with his grandmother, Korsmo remembers being a little disappointed in the film, feeling that it didn’t hold together in the way that it was intended. The most memorable thing about their evening was the fact they were seated right behind Sean Connery.

“I remember when we were filming the sequence where the crocodile falls down,” said Korsmo. “It looked like a pretty cheesy mechanical thing. When the jaw opened, it bounced up and down a couple times. At the time, Steven was in preproduction on ‘Jurassic Park,’ and I remember him sitting there with his head in his hands. It was as if he was thinking to himself, ‘How the hell am I going to do ‘Jurassic Park’ in six months if this is the best we can do with an animatronic crocodile?’ As the shoot dragged into its fifth month of shooting, Steven was pointing out that the only movie he ever made that went over schedule and over budget was ‘Jaws.’ He’s usually known for extremely fast, efficient and almost improvisational shoots. It only took two months for ‘Saving Private Ryan’ to be shot, whereas ‘Hook’ stretched on forever.”

“Michael Kahn, who is Steven’s brilliant editor, edited the movie in the way that it was structured, not the way that it was shot,” said James. “The movie works because Michael got the structure right. He actually called me one day and said, ‘You’re gonna be happy, we got it right.’ But if you notice, after the food fight where Robin is covered in paint, the film cuts to him in his glasses and tuxedo, which are clean, when he is up on the bridge and given the lost marbles. So clearly, that was not the way Steven had shot the scenes to be ordered. So you have those kinds of snafus and continuity issues throughout the movie. When Dustin hands the ball to Charlie, I said to Steven, ‘You have to cut to the baseball game. You can’t go anywhere else because you’ve keyed up the audience for the game.’ Instead, he put Amber’s song in between those scenes, so it happened completely out of context. Thankfully, in the completed film, he cut directly from Hook handing Jack the baseball to the ballgame as I had suggested.”

“Jim had written an amazing script that he originally had made sure was available for a lower budget,” said Goodall. “I saw Jim navigate the many versions of scripts coming through with such aplomb that you had no idea that he was madly paddling underneath. He always came up with an alternative scene if it was wanted, and remained so supportive and positive all the way through the production. If Jim hadn’t picked it up and dragged it on his own shoulders as well, I think ‘Hook’ wouldn’t be the film that we all remember. It was the script that Steven was drawn to right off the bat. I honestly think that the subsequent inflating of the budget is why Steven ended up making ‘Schindler’s List’ a few years later. It was, as far as Steven was concerned, honed down and low-budget—well, for him it was—which provided him with a sense of autonomy. I actually think ‘Hook’ was a watershed for Steven in that it propelled him to make some changes in what he wanted to shoot in the future and the stories that he wanted to tell. The heart of ‘Hook’ and the important themes it tackled set him off on a path to tell the most important story of his career that he was perhaps too frightened to tackle up until that point.”

Years later, when Willams was filming the picture that would finally earn him an Academy Award, “Good Will Hunting,” while sporting a full beard, he was floored when kids would stop him on the street in Boston and go, “Hey, you’re Peter Pan!” According to Jake, when it came to being inclusive onset, no one topped Robin, and his generosity was not limited merely to his work hours.

“My best experience with Robin was when I was in college,” said Jake. “He was being interviewed for ‘Inside the Actor’s Studio,’ and my sister and I went. I had to leave early because I was in college directing a production of Twelfth Night, and I was one of those idiots who was like, ‘Well, I have a show, I can’t skip it to watch Robin Williams get interviewed!’ So when I explained this to him prior to the show, he talked to me about Twelfth Night for about fifteen minutes. He knew the play and he wanted to hear what I was doing with it. He was about to get onstage in front of a million people, and yet he still wanted to sit down and hear what my thoughts on the play were. That’s the kind of guy he was.”

James teamed up again with Castle and Williams for Kirsten Sheridan’s 2007 crowdpleaser “August Rush,” a drama hinging on the miraculous power of music to reunite the titular prodigy (Freddie Highmore) with his birth parents. Critics at the time—myself included—derided the film for being implausible, despite the fact that a similar story about a young student at Juilliard occurred just months before the film’s release. While revisiting the film prior to this interview, I was surprised to find myself and my fiancée reduced to tears by the end of it, proving just how rewarding a moviegoing experience can be when viewed at a different time in one’s life.

Among the few critics who praised the film was Roger Ebert, who wrote the following in his three-star review: “Here is a movie drenched in sentimentality, but it’s supposed to be. I dislike sentimentality where it doesn’t belong, but there’s something brave about the way ‘August Rush’ declares itself and goes all the way with coincidence, melodrama and skillful tear-jerking. […] The movie seems to sincerely love music as much as August does. If you’re going to lay it on this thick, you can’t compromise, and Sheridan doesn’t. I don’t have some imaginary barrier in my mind beyond which a movie dare not go. I’d rather ‘August Rush’ went the whole way than just be lukewarm about it. Yes, some older viewers will groan, but I think up to a certain age, kids will buy it, and in imagining their response, I enjoyed my own.”

The most harrowing part of the picture is Williams’ uncompromisingly wounded performance as Wizard, an embittered leader of Dickensian lost boys—in this case, street performers—whose fixation on August’s extraordinary musical talent quickly turns possessive.

“It was the last time I worked with Robin, who was unraveling,” said James. “Six weeks after the film, he was in rehab. They brought me in because they wanted me to write the part for Robin so he would do it. Wizard’s character was only in ten pages of Nick Castle’s script. My job was to turn Wizard into an important part of the story. I wrote this really dark character, and we had to cut stuff out that was too painful to watch. There’s a moment where he hit Freddie, and he had a hard time doing it. It’s like that moment in ‘Hook’ where he’s frighteningly explosive and you see that dark side of him, but Wizard is dark anywhere. There was also a scene we shot in the subway where he’s trying to keep August from getting to the concert. He tells August that he used to be a great musician and he lost it, and he just wants August to play for him so he could be renewed and restored and maybe rekindle his own gift. He keeps handing August a guitar and we had to cut it out because it was too powerful, too painful and it stopped the movie. Robin was in that dark place for real.”

Williams died just four months after Hoskins, which reduced Jake to a mess of tears when watching the film at a twenty-fifth anniversary screening.

“The conversation of my life was with Bob Hoskins,” said Jake. “I had graduated college and we were in London hanging out with John Napier, who was the film’s visual consultant, and Bob was like, ‘What do you want to do?’ I replied that I wanted to do what they did, and he was very insistent on saying, ‘You need to take some time and get away from all of this madness. You need to go do something else—even if it’s being an usher in a theater. Do not jump into this right away.’ I still have a picture of Bob and me at the ripe old age of 21 on this trip, and it will be next to every desk I ever have. The type of person Bob was and the energy he put out in the world is something I can only aspire to be someday. The amount of records I have, books I’ve read and movies I’ve seen because he told me to I couldn’t even begin to count. He was very much an uncle to me.” Jake ultimately took Hoskins’ advice and performed as a member of the Blue Man Group in Boston for five years.

Thirty years after its release, “Hook” has deservedly acquired the status of a cult classic, and no one has felt its impact more meaningfully than Basco. As soon as Rufio appeared onscreen, the kids of my generation viewed him as the epitome of cool. We begged our teachers to show the film at our elementary school, but they rejected it due to the food fight scene (not the scene where Rufio is murdered, oddly enough).

“As your career goes on, you see what those characters meant to people and representation,” said Basco. “When ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ came out, Jon M. Chu—who has since become a friend—said in an interview, ‘Seeing Dante Basco play Rufio in ‘Hook’ as a kid in a movie theater was my first moment where I thought I can be a part of this industry.’ This is how the film has connected to the next generation. People have often told me, ‘You are the first cool and non stereotypical Asian I ever saw in a Hollywood film or television series,’ and it’s not something that I set out to do, it’s just how my career unfolded. Rufio was a big part of that because up until that moment, no one had seen an Asian character like that in mainstream American movies. That character has become a cultural hero to a lot of people, and not just Asian Americans. I’ve seen tattoos on people’s bodies of my 15-year-old face with the tri-hawk.”

“I wish I had known all these years how beloved the film has become, and it wasn’t until the last five years that I really understood its legacy,” said Jake. “I’m in a band in which everyone is ten years younger than me, and when they found out my dad wrote ‘Hook,’ they lost their minds. The film works for the people it was meant to work for, and if critics don’t get it, it doesn’t matter. People still love it, dad’s residual check at the end of the year is still solid, and I’m sure if I read some of the reviews that were written back then, I’d be like, ‘Yeah, I think that tracks,’ or, ‘I agree with this, that and the other.’ The way it has spanned generational and cultural divides to sort of unify people can’t be topped. Not every movie has that sort of impact, so they must’ve been doing something right.”

Basco gained further popularity by voicing the character of Zuko in the Nickelodeon series, “Avatar: The Last Airbender,” which ranks among the great modern fantasy epics. It was just last month that he spoke with me via Zoom from Belgium, where he made his latest appearance at a comic convention.

“I was at a comic con about a month or so ago, where I was signing autographs and people were talking to me about how I had impacted their lives,” recalled Basco. “I looked up and saw that I was sitting right across the way of William Shatner, who is now 90 and still signing autographs for ‘Star Trek’ fans. Rufio and Zuko are characters that either I am going to carry or they are going to carry me into my nineties no matter what other iterations of these stories occur. When I attended the screening Michael B. Jordan hosted of ‘Hook’ last year, we talked about representation, and what I mentioned is that ‘Peter Pan’ stands apart from most any other fantasy because it’s not a franchise—it’s a fairy tale. ‘Peter Pan’ has been around longer than anyone alive on the planet today, and it will still be around after we’re all dead. Somehow, through the magic of Spielberg, I have become a part of that fairy tale forevermore. When you attend a comic convention or Disneyland or see a group of trick-or-treaters on Halloween, you will see someone, whether they are ethnic or not, representing a person of color in canon in that world. When Captain Hook, in modern adaptations, says, ‘Remember what happened to Rufio…’, it continues the legend.”

The legend was further expanded by filmmaker Jonah Feingold, who pitched a Rufio origin story to Basco that turned into the short film, “Bangarang,” which Basco appears in as well as executive produced. Now Basco and Jake have teamed up with Jay Oliva and Lex + Otis Animation to develop a series about a Filipino lost boy who is new to the island of Neverland.

Two decades after Basco starred in the first Filipino American feature, Gene Cajayon’s “The Debut,” a film that was praised by Ebert, the prolific actor and producer has made his solo directorial debut with “The Fabulous Filipino Brothers,” which premiered at this year SXSW and features his real-life siblings Darion, Derek, Dionysio and Arianna. Each brother is the subject of a vignette that takes place at a Filipino wedding and is inspired by personal stories from their lives.

“It is a very unique experience because my brothers and I have a shorthand,” said Dante. “They know every moment that we’re stealing from in our lives, whether it be a story from our family or something that we all grew up watching, from ‘Midnight Cowboy’ to a play like Hurlyburly. This is one of those special films where everything we’ve collectively done over the last 35 years has led us up to making this movie right now. It’s a family comedy and I cannot wait for people to see it. We’re going to be touring the country when it’s released digitally in February. As with ‘The Debut,’ I want to use the film as a catalyst to celebrate the Asian American arts community, talk about what’s going on collectively, and inspire the next generation of filmmakers to make movies. Our stories count now more than ever, and it’s our time to share them with the world.”

When I spoke with Basco about how “Hook” is ripe for critical reassessment, he mentioned reading in the book Pictures of the Revolution about how Ebert, during his first full year as a published critic, was one of the few pundits to hail “Bonnie and Clyde” as a great and important picture upon its initial release. He feels that the split opinions on “Hook” are a sign of the generational gap that has been further escalated by transformative change.

“I saw this weird TikTok video where a guy was talking about how the Mayans’ prediction that the world would end on December 21st, 2012 turned out to be true because it proved to be a moment of change,” said Basco. “If you look at the technology and music that came before that period, it’s almost like night and day. Even when you look at Steph Curry, he’s playing a whole different kind of basketball. We’ve just accepted we’re in a different age of what is possible. There’s many ways for the world to end, and maybe it did.”

Aside from 1998’s teen comedy, “Can’t Hardly Wait,” Korsmo left screen acting altogether after “Hook,” and began his career thirteen years ago as a corporate law professor. He vividly recalls a pivotal exchange he had with Hoffman while they were cooling down below decks in their pirate costumes, which were especially sweltering when the soundstage reached 100 degrees.

“I spent many afternoons down there with him,” said Korsmo, “and he would say to me in character, ‘You are too smart to be working in a circus like this. Get out while you still can!’ Whether he was serious or not, he was right that if I had stuck around Hollywood until I was 14 or 15, my life would’ve been very different. My family never moved to Los Angeles, so I was always flying back and forth. I woke up one day when I was 13 and ‘Hook’ was done. I had two brothers and a stepfamily at the time, and everyone would have new stories to share around the dinner table about funny stuff that happened with their friends and at school. I hadn’t had a story like that for the past three or four years, and that’s one of the reasons why I stepped away from acting.

I was a corporate lawyer for a few years, and it was pretty consuming. I remember one of the partners whose kid was in kindergarten and had drawn a picture of his family—and it didn’t have the dad in it at all. It’s not quite as bad as the one Jack draws in ‘Hook’ of his dad going down in flames, but it still isn’t great, so when I had kids, I grabbed the parachute for academia. There are things I like about the job as well as things I wish were a little more tangible. But in terms of the flexibility, scope and opportunity to work on things that are interesting to me, it’s a tough job to beat.”

After two decades without a screen credit, Korsmo was finally wooed back to act in one of 2018’s best films, “Chained for Life,” directed by the actor’s longtime friend, Aaron Schimberg. Though it may have been purely coincidental, the film does indeed contain a pointed reference to Captain Hook.