In a world where the imagination of indie sci-fi can often struggle to match its lower budgets, we can be grateful that “Divinity” (with a “Steven Soderbergh Presents” in the opening and end credits) exists in all of its wacky glory. Here is a cornucopia of aesthetics, not for all but definitely for some, that will remind you that not every type of film has been made yet.

With some squinting, the movie almost plays like an answer to a business whose genres and scales have been eaten away by mega-budget stories, their spectacle numbed by their incessant apocalyptic stakes. Writer/director Eddie Alcazar seeks to provide the spectacle we are inundated. That’s at least how I read a hyper stylized stop-motion battle later in the movie that’s hopped up on video games, anime, and not following any rules about how action should be done.

“Divinity” has a good log-line: two twins (Jason Genoa and Moises Arias) crash into a dying Earth to stop a man named Jaxxon (Stephen Dorff) from making an immortality potion named Divinity, that his father (Scott Bakula) had worked on before dying. The potion promises its customers the ability to stop aging in the mind and body, but it’s revealed that the process also demands fetuses, which is bad news for a human civilization with a 97% infertility rate.

When the twins strike, imprisoning Jaxxon and pumping him with his shallow salvation juice, the side effects are monstrous. His head grows macho muscles over his eyes, and a Frankenstein arc begins. The special effects in “Divinity” are great, and so is Dorff’s performance in the process. With so much on its mind and in its aesthetic arsenal, this plot is overshadowed by more indulgent passages about the anti-salvation of Divinity. Such passages involve Jaxxon’s mega-buff brother (Michael O’Hearn) and his universe of skin, muscle, and conventional beauty.

Sometimes star power seems like an endorsement, and that’s certainly the effect here: its actors have their names flash in its intense opening credit sequences, and then they get to ham it up; they are in on “it,” whatever “it” is. A stern Bella Thorne plays a cult leader named Ziva; she is flanked by a coven of young women in white spandex, and a vessel for some of the story’s sanctimonious lines. Karreuche Tran’s docile Nikita may be the world’s only hope, though she is unaware of it when caught up in bed with the twins. Scott Bakula appears in flashbacks we mostly see from VHS clips, talking about his attempts to crack the formula for Divinity. This is just a taste of the always off-kilter world of Alcazar’s film, which fuses analog technology, modern architecture, and pessimistic futurism all together.

“Divinity” is a thoroughly alien film—apart from feeling like an a cinematic piece of outsider art, it speaks its own language. That makes it compelling but also confounding regarding what it wants to say—is it condemning machismo with its scenes of conventionally beautiful people who take Divinity or indulging in it? There are so many specific choices to this production, which is like an alien transmission to comment on all of society, including our value of superficial beauty or our selfishness with resources.

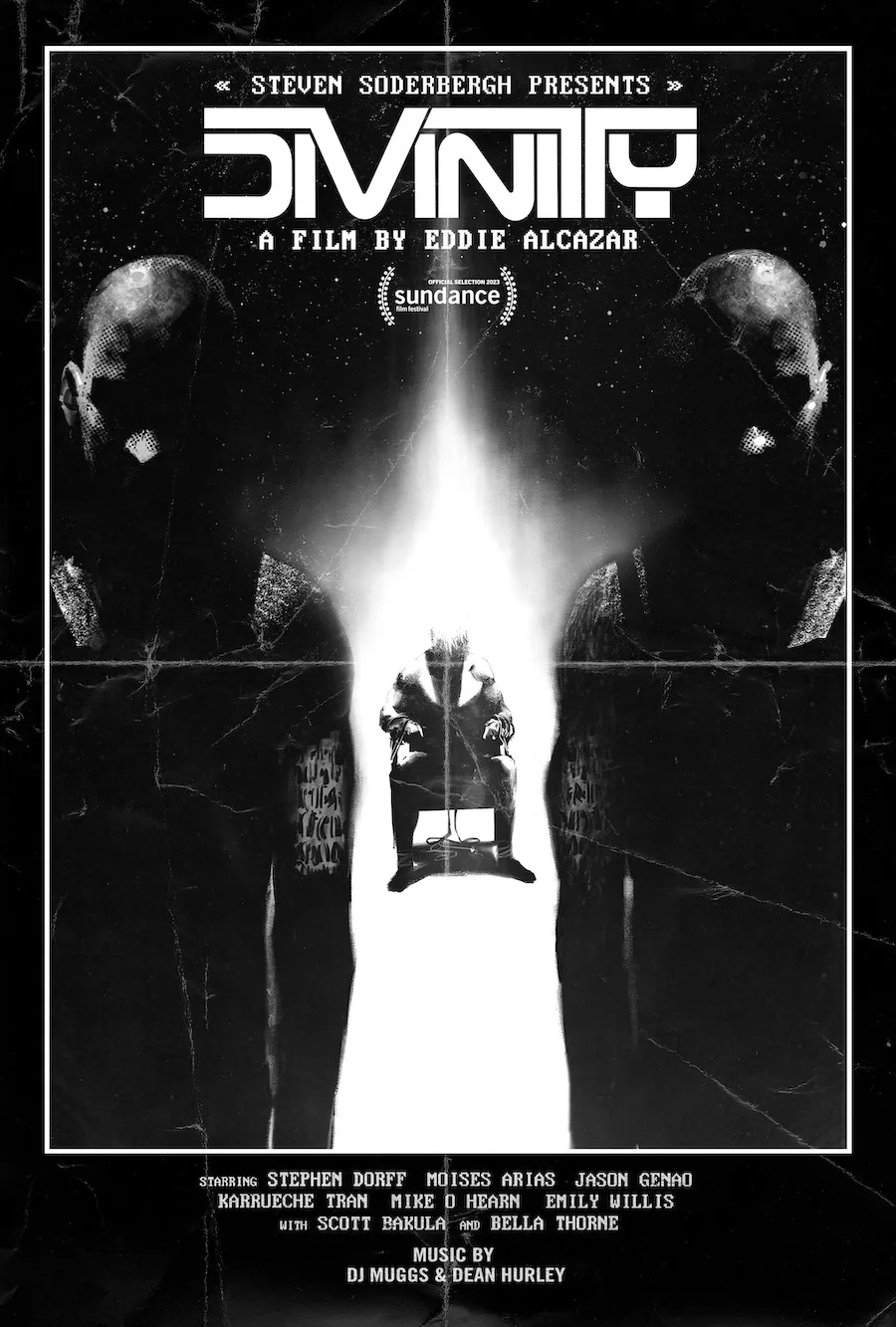

However one reads it, “Divinity” has no interest in a response or conversation, which, when paired with how seriously outrageous the visuals are, makes it fascinating, if not exciting. Alcazar has thrown in stuff that would be extra corny in daylight and color, so he douses the image with darkness, using backlighting for his black-and-white movie throughout. With the help of a special Kodak film stock, the black and white look is one of the ways in which this movie earns being taken seriously, while also hiding the indie bits. With such harsh black and white, underexposed as much as it can be, it wins your fascination.

In Earth terms, “Divinity” is weird as hell, but the movie doesn’t know that. It risks the symptom of many bad movies, of being so far up its you-know-what that its stoic performances welcome scoffs. And yet “Divinity” staunchly doesn’t care if you like it or question it. Its entertainment factor, made possible by strong pacing, is even incidental—the film’s style is built around esoteric monologues, abrasive moments of violence, and overtures about brothers and fathers. When it’s time, Alcazar’s script smashes such broad themes together in this grandiose place he has made for himself.

The movie’s jolts of sci-fi and horror are primed for Midnight audiences, though “Divinity” makes about as much half-sense in the daylight or the nighttime (or after multiple viewings). Whenever you view it, know that it’s not for those who want to find movies they can feel smarter than. “Divinity” is the very definition of a film that’s high on its own supply. Take its wonky, singular rush, or don’t.

Now playing in theaters.