There’s a temptation when faced with a film like “Endgame” to give it a pass as harmless family entertainment. It has its heart in the right place and is eager to please. The real-life triumph of the disenfranchised public school students from Brownsville, Texas, who became chess champions is inarguably inspiring. Their story is certainly worthy of being told, but director Carmen Marron has greater ambitions. She also wants to tackle damaged family bonds, teenage death and the tragedy of deportation faced by illegal immigrants. “Endgame” tries to be about many important issues, and ends up doing none of them justice.

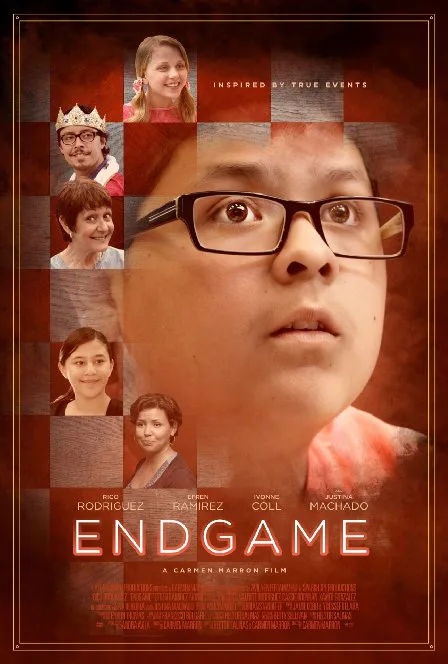

That’s a shame, considering how the film could’ve been a refreshing dramatic showcase for sitcom star Rico Rodriguez. He’s a young man of ample girth who wears glasses—a prime target for bullying at his age—yet he never utilizes his appearance to acquire cheap laughs. He looks like any other normal kid, struggling to find his place in the world while grappling with the ever-present nuisance of puberty. The fact that his words don’t ring true in “Endgame” may have less to do with his seven seasons on “Modern Family” and more to do with the script by Marron and Hector Salinas, which appears to have been stitched together entirely from recycled fragments of Afterschool Specials.

This is the sort of film where a teacher gives an inspirational pep talk to a student while standing in front a sign that reads, “INSPIRE.” The fictional narrative contrived here isn’t a fleshed-out story so much as a list of bullet points. None of the emotional payoffs are earned because nothing is adequately developed. We see young Jose (Rodriguez) excelling at chess while under the tutelage of his grandmother (Ivonne Coll) and devoted coach (Efren Ramirez), yet we get no real sense of his technique. There are numerous overhead shots of pieces being shifted and checkmates being declared, but little context as to how the game actually works. A scene where the teacher instructs students to practice on a life-sized chess board is no help, since it’s more concerned with the mugging cuteness of the kids’ dance moves.

Similarly, the audience is never allowed to share in Jose’s grieving process after his older brother, a celebrated star of the school soccer team, dies in a car accident that plays like a self-contained anti-drug ad. Any trace of the boy’s despair is left offscreen, leaving his mother, Karla (Justina Machado), with the unenviable task of supplying the otherwise absent emotion, all the while being thoroughly unlikable. There’s no question that the older brother was Karla’s favorite, and with him gone, she focuses solely on her own suffering, while treating Jose with cold indifference. A few of her lines would make even Mary Tyler Moore’s icy matriarch in “Ordinary People” shudder. When a beloved companion of Jose’s is snatched by border patrol officers, Karla can’t muster any words of consolation apart from, “Well, I’m sure you’ll make other friends.”

The deportation subplot comes completely out of left field and is so whiplash-inducing in its haphazard placement that it elicits incredulity rather than empathy. You can practically hear the soap opera clang on the soundtrack as this twist is revealed, only to be swiftly abandoned long before the final act. Marron does a disservice to this monumentally topical issue by treating it like an arbitrary plot point. The same could be said about Karla’s inner demons, which she finally reveals in the film’s only instance of raw feeling. She lashes out at her mother for being distant throughout her childhood, choosing to focus on chess tournaments rather than her maternal duties, and then accuses the blindsided woman of using chess to place a wall between her and Jose. It’s an effective scene, but it establishes a dynamic that is never developed beyond the stage of a first draft. How do the mother and daughter make amends prior to the happy ending? You won’t find out by watching the movie.

Another germ of a good idea emerges in scenes involving the chess coach played by Ramirez, formerly Pedro of “Napoleon Dynamite,” who fares the best of anyone else in the cast. He’s barely making end’s meet, yet still is bound and determined to guide his students toward what he hopes will be a successful adulthood. He’s also a vulnerable human himself, and is barely able to conceal his desperation as the kids’ motivation starts to wane. “Would I be investing my rent money in you if I didn’t think you could do it?” he exclaims while straining to smile. “So come on, don’t make me homeless!” It’s a funny line, even if it’s essentially an expository one. Anytime this impoverished teacher materialized onscreen, I thought to myself, “Now there’s the movie.”