The personal essay film is a tricky genre, because when you get right down to it, who cares? Sure, there is a brotherhood of man and all that, but is it such that we’ll be interested enough in a brother’s struggles that we’re willing to sit with them for a while in a movie theater, not to mention shell out money for the experience?

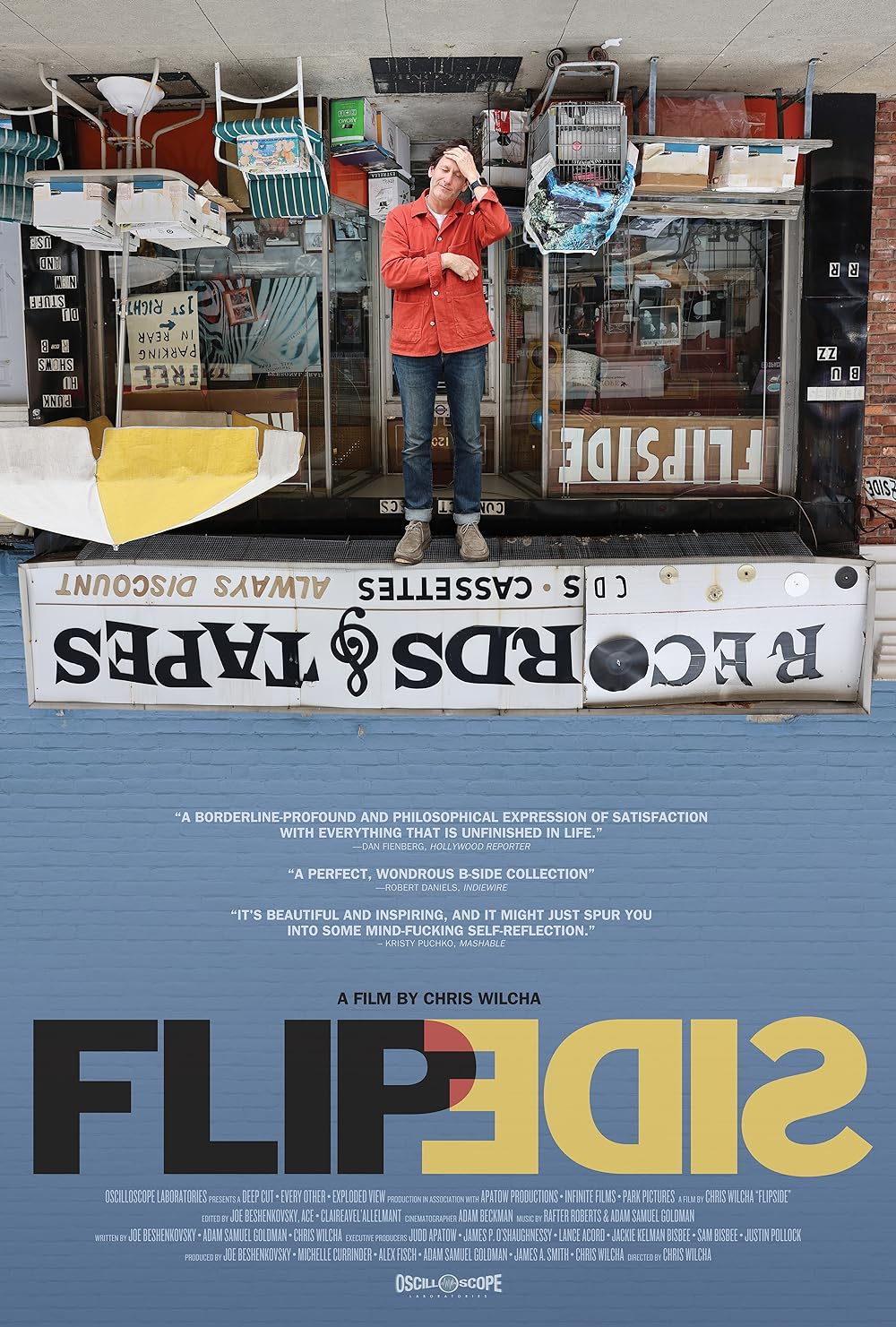

These questions represent perhaps crass generalizations that crowd out the potentially dire and potentially universal themes and narratives that a personal documentary can encompass, but you get the idea. And the idea applies with particular pertinence to this movie, “Flipside,” which winds up making us care about the existential crisis of a white, possibly upper-middle-class male with no health issues, an apparently lovely family, a high-end profession in a form of filmmaking, and a lot more to be happy about.

The writer-director of “Flipside,” Chris Wilcha, pulls us in through indirection. He starts the movie with a portrait of Herman Leonard, a music photographer, who sits in a gallery surrounded by his portraits of the likes of Nat “King” Cole and Chet Baker and muses that “every life is a trip” and “you are the captain of your boat.” These platitudes gain some real weight when Leonard tells us he’s dying. Wilcha then informs us that the footage we’re watching is from a documentary he started but never finished. Turns out he’s got a bunch of them.

“Flipside” then depicts how this state of affairs came to be. Wilcha presents a brisk account of his early years, the no-sell-out grunge ethos he grew up with as a Gen Xer, and how, upon taking a corporate job at Columbia House, he interrogated a system he despised from the inside, actually finishing an eventually well-regarded 2000 documentary “The Target Shoots First.” Predictions that he could be the Gen-X Michael Moore ran headlong into Wilcha’s need to make a living, which led to ostensibly meaningful jobs like a gig at “This American Life.” But largely, Wilcha made commercials. Becoming the thing he beheld and disdained.

Seeking something like redemption or legitimacy or … well, meaning, Wilcha found his way back to a record store in Pompton Lakes called Flipside, where he had a job as a teenager. (A Jersey boy myself, I’ve actually set foot in the joint at least once.) Its proprietor, referred to throughout only by his first name, Dan, is, like Wilcha, something of a hoarder. This gives the spot its distinct flavor but also makes it an awkward business in the digital age. Wilcha’s initial resolve to make a film to help the business diffuses over time and becomes another unfinished project.

Given that this is a finished movie, there is a story here, one with a conclusion. And one that pulls in a lot of notable names. Judd Apatow, also the movie’s executive producer, is here. He’s the guy who got Wilcha to move to Los Angeles in the first place, inadvertently setting the filmmaker’s boat in the direction of advertising work. (He also provides one of the movie’s paradoxical axioms: “It’s not hoarding if all your shit is awesome.”) “Deadwood” creator David Milch figures. So does Floyd Vivino, aka Uncle Floyd, the Jersey cult legend whose oddball VHF television show entranced the artistic cognoscenti across the Hudson to the extent that David Bowie, seen here in archival concert footage, wrote a song in which Floyd and his puppet Oogie are talismanic personae. All of whom address, in some way or another, the question of how one does work that’s meaningful in a world that often seems hell-bent on squelching meaning. Whatever “Flipside” ultimately “means,” it’s ninety minutes well, and often amusingly and movingly, spent.