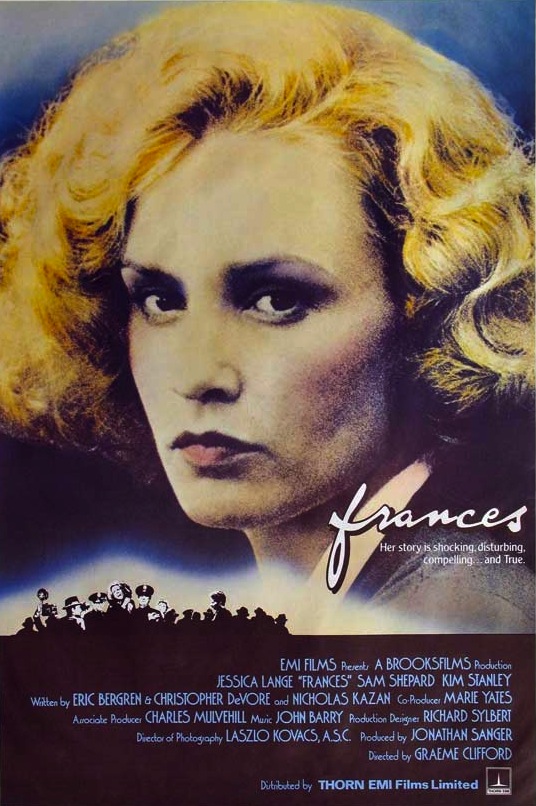

Graeme Clifford’s “Frances” tells the story of a small-town girl who tasted the glory of Hollywood and the exhilaration of Broadway and then went on to lead a life during which everything went wrong. It is a tragedy without a villain, a sad story with no moral except that there, but for the grace of God, go we.

The movie is about Frances Farmer, a beautiful and talented movie star from the 1930s and 1940s who had a streak of, independence and a compulsion toward self-destruction, and who went about as high and about as low as it is possible to go in one lifetime.

She came out of Seattle as a high school essay-contest winner and budding intellectual. She was talented and pretty enough to make her way fairly easily into show business, where she immediately gravitated to the left-wing precincts of the Group Theater and such landmark productions as Clifford Odets’ “Waiting for Lefty.” She also became a movie star, and there was a time when her star shone so brightly that it seemed the party would last forever.

It did not. She was a stubborn, opinionated star who fought with the studio system, defied the bosses, drank too much, took too many pills and got into too much trouble. Her strong-willed mother stepped in to help her, and that’s when Frances’ troubles really began.

The mother orchestrated a series of hospitalizations in bizarre mental institutions, where Frances Farmer was brutally mistreated and finally, horrifyingly, lobotomized. She ended her days as a vague, pleasant middle-age woman who did a talk show in Indianapolis and finally died of alcoholism.

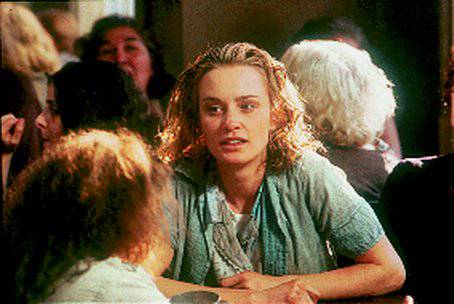

Jessica Lange plays Frances Farmer in a performance that is so driven, that contains so many different facets of a complex personality, that we feel she has an intuitive understanding of this tragic woman.

She is just as good when she portrays Farmer as an uncertain, appealing teenager from the Northwest as she is when she plays her much later, snarling at a hairdresser and screaming at her mother. All of those contradictions were inside Farmer, and if she had learned to hide or deal with some of them she might have lived a happier life.

The story of Frances Farmer makes a fascinating movie, if only because it’s such a contrast to standard show-business biographies. They usually come in two speeds: rags to riches, or rags to riches to victim. “Frances” never really lays blame for the tragedy of Farmer’s life.

It presents a number of causes for Farmer’s destruction. (A short list might include her combative personality, her shrewish mother, the studio system, betrayal by her lovers, alcoholism, drug abuse, psychiatric malpractice and the predations of a mad lobotomist.)

But the movie never comes right out and says what it believes “caused” Farmer’s tragedy. That is good, I think, because no simple explanation will do for Farmer’s life. The movie is told from her point of view, and from where she stood she was surrounded. On one day she had one enemy, and on another day, another enemy. Always, of course, her worst enemy was herself.

The movie doesn’t let us off the hook by giving us someone to blame. Instead, it insists on being a bleak tragedy, and it argues that sometimes it is quite possible for everything to go wrong. Since most movies are at least optimistic enough to provide a cause for human tragedy, this one is sort of daring.

It is also well made by Clifford, a first-time director whose credits as a film editor include such virtuoso work as “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” and “Don't Look Now.” Clifford has made a period picture that wears its period so easily that we’re not distracted by it, and he has made a movie that is bleak without being unwatchable.

There are a few problems with his structure, most of them centering around an incompletely explained friend of Farmer’s, played by Sam Shepard as a guy who seems to drift into her life whenever the plot requires him. Kim Stanley plays Farmer’s mother on a rather thankless note of shrillness, and the lobotomist in the picture seems to have wandered over from a nearby horror film. (He apparently gave the same impression in real life.)

But Lange provides a strong emotional center for the film, and when it is over we’re left with the feeling that Farmer never really got a chance to be who she should have been, or to do what she should have done. She had every gift she needed in life except for luck, useful friends and an instinct for survival.

She might have been one of the greatest movie stars of her time. As it is, when I was asked the other day to name a few of Frances Farmer’s best films, I had to admit that, offhand, I couldn’t think of one.