“Anyone who leaves the cinema doesn’t need the film, and anybody who stays does.”

— Michael Haneke on his previous version of “Funny Games”

The new Hollywood edition of “Funny Games,” writer-director Michael Haneke’s clinical reenactment of his Austrian torture-comedy experiment from 10 years ago, is an attempt to replicate the earlier study under English-language conditions.

You (the lab rat) are placed in a Skinner box (the movie theater) and subjected to random negative stimuli (filmed violence, as a substitute for painful electrical jolts). Haneke, whose academic background is in psychology, philosophy and theater, assumes the role of empirical taskmaster. He hypothesizes that his box will shock you into a knee-jerk ethical dilemma. To pass the test, you must reject the false premise of the experiment itself (if only on the grounds of insufferable smugness) and walk out.

An even better response, theoretically, would be to storm the booth and rip the film out of the projector, thus symbolically declaring your refusal to swallow the force-fed medicinal doses of synthesized abuse the film is administering. And if you really wanted to ace the challenge, you would just not see the movie.

But if you liked those pictures from Abu Ghraib, you’ll love “Funny Games”! See the captors tighten a pillowcase over a young boy’s head, force Mom to strip (no actual nudity shown) by the TV, smash Dad’s leg with a golf club and play hide and seek with the body of the family dog they’ve just killed with the same driver! For the price of a ticket, you can choose the level and nature of your vicarious involvement with the sadism on the screen, and the masochism in your seat. Enjoy.

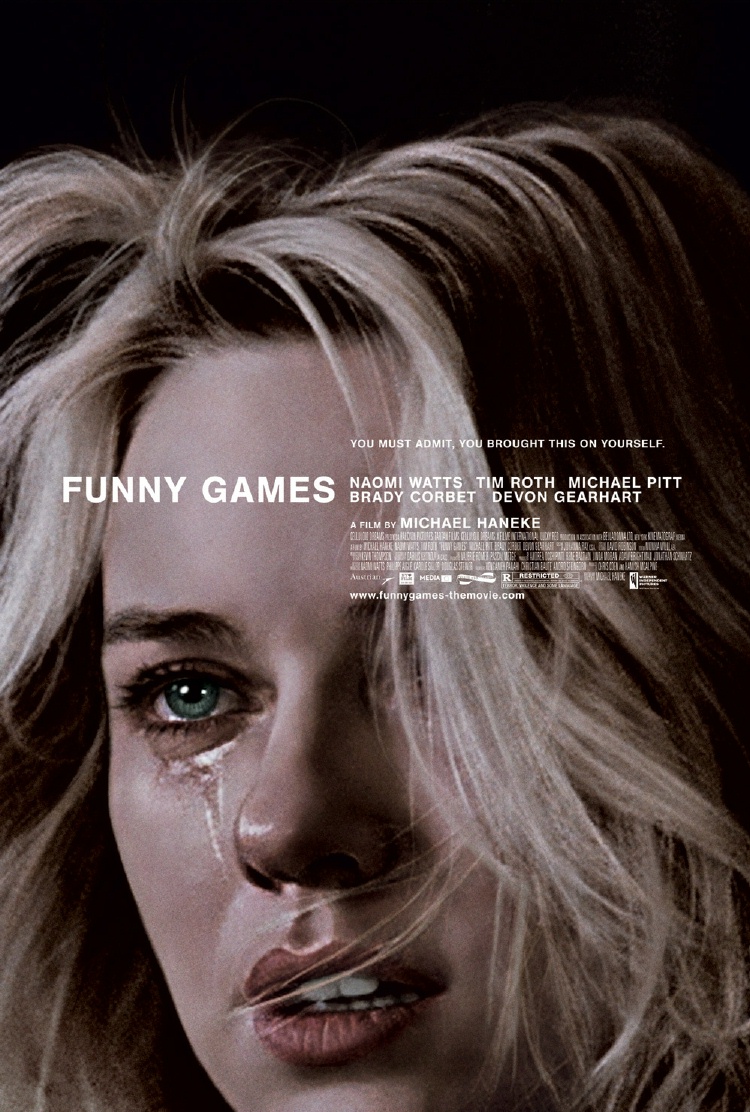

The game’s narrative parameters are as follows: A dubiously American bourgeois family — Ann (Naomi Watts), George (Tim Roth), their pre-teen son Georgie (Devon Gearhart) and their golden retriever — arrive at their vacation home on Long Island. They are upper-class ciphers who stock soy milk in the refrigerator, feed their dog expensive Wellness brand kibble and keep a Tivoli radio in the kitchen. The attention paid to the details of their conspicuous consumption may or may not express the film’s attitude: that these cardboard caricatures somehow deserve to be humiliated, tormented and killed for exhibiting Eurocentric yuppie tastes, including implicitly sinful predilections for golf, boating and classical music. Or maybe the movie is simply suggesting that you give yourself permission to feel that way.

Two symbolic young men, Paul (Michael Pitt) and Peter (Brady Corbett), show up at the screen door, dressed in shorts, canvas shoes, white sweaters and white gloves. They proceed, politely and methodically, to terrorize, torture and murder their hostages, offering a rigged “bet,” in the guise of “entertainment,” on behalf of the film: that all family members will be dead by a certain hour. Meanwhile, the victims are bludgeoned into submission and despair. The torturers are blandly passive-aggressive and genteel, their motiveless actions appearing alternately logical and irrational, inexorable and impulsive, cruel and — even more cruelly — kind. The movie’s running time is 1 hour and 52 minutes.

Every once in a while, Paul addresses the camera with a conspiratorial smile or a nudge-nudge, wink-wink joke. He guesses that “you [the audience] are probably on their [the victims’] side.” He and Peter represent the film’s side. What do you want to bet they will win the already-decided bet?

As an academic exercise in learned helplessness, the film flaunts the ultimate power to rewrite its own “rules” whenever it likes, including taking back anything that has already been shown. A movie with no restrictions holds no real suspense, and no surprises, so any revelation of plot details in, say, a review, is meaningless.

What makes “Funny Games” different than any other campy-scary horror movie that gets off on tormenting its characters and teasing its audience? Not much. It’s being pitched to the “Hostel” crowd (who are invited to laugh) and the art-house crowd (who are invited to feel ennobled as they shake their heads and lament the state of violence in movies).

Haneke (whose masterworks include “Code Unknown” and “Cache”) explains that his distinctively European film is “a reaction to … the way American cinema toys with human beings … [so that] violence is made consumable.” That’s true, and it’s what “Funny Games” sets out to do, but Haneke’s essay fails because he hasn’t a clue about what makes American movies tick. “Funny Games” doesn’t seduce you with conventional storytelling and character development and then turn them around on you — like, say, Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rear Window” and “Psycho.” Instead, as the press kit explains, it encourages its viewers “to see their own role through a series of emotional and analytical episodes.” In other words, this isn’t a movie, it’s a thesis.

“Funny Games” represents the laborious execution of an abstract notion. The concept is the movie, kind of like Andy Warhol’s ”Empire” (1964), an eight-hour stationary shot of the Empire State Building. You don’t have to sit through the whole thing to get the point, unless you really want to.

> > > >

Read more and participate in the discussion at Scanners here:

http://tinyurl.com/ynwyak