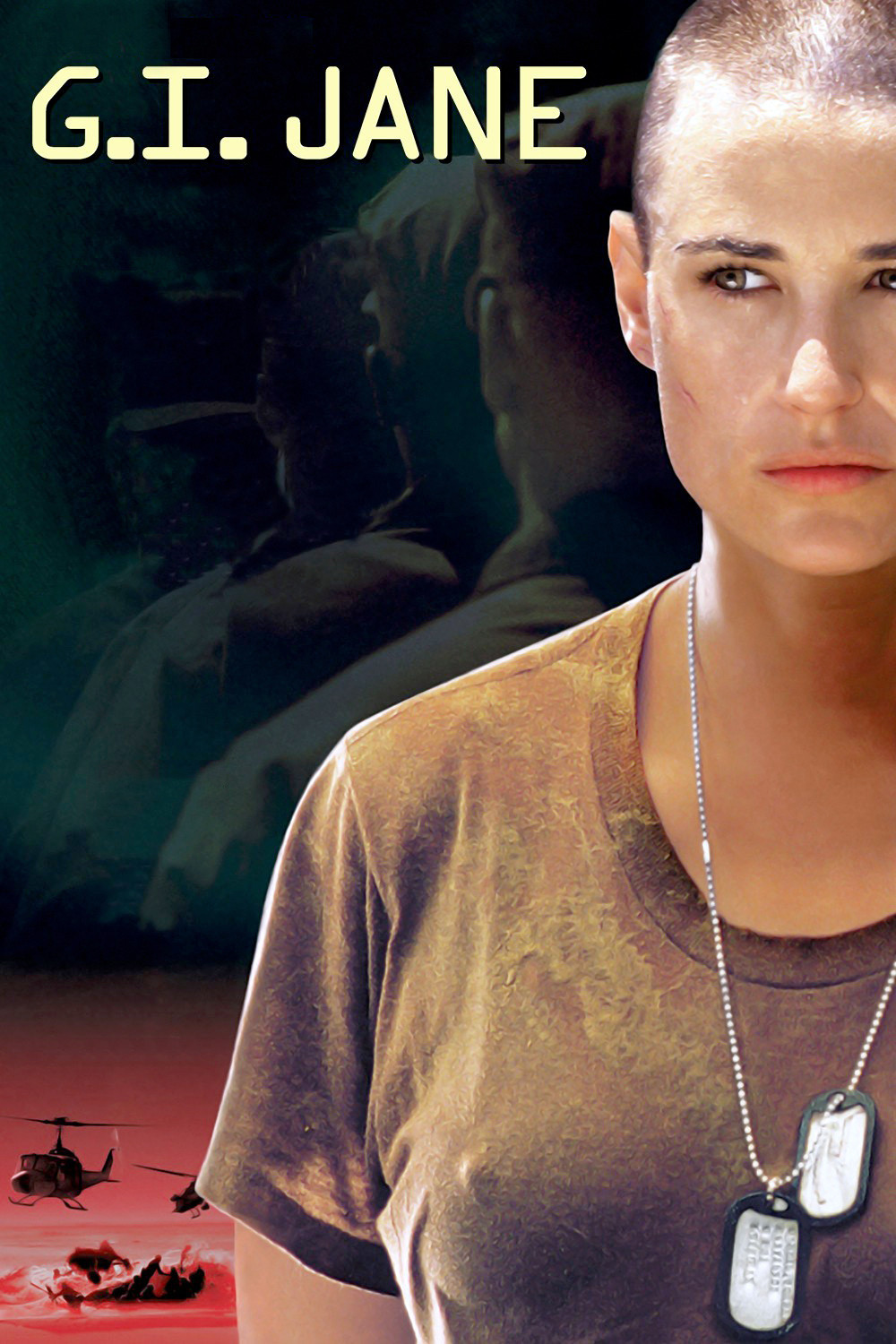

“I’m not interested in being some poster girl for women’s rights,” says Lt. Jordan O’Neil, played by Demi Moore in “G.I. Jane.” She just wants to prove a woman can survive Navy SEAL training so rigorous that 60 percent of the men don’t make it. Her protest loses a little of its ring if you drive down Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, as I did the other night, and see Demi Moore in a crewcut, glaring out fiercely from the side of an entire office building on one of the largest movie posters in history. Well, the lieutenant is talking for herself, not Moore.

Jordan O’Neil is a Navy veteran who resents not being allowed into combat during the Gulf War. Now there’s a move under way for full female equality in the fighting forces. Its leader, Sen. Lillian DeHaven (Anne Bancroft), wants no more coddling: “If women measure up, we’ll get 100 percent integration.” O’Neil is selected as a promising candidate, and reports for SEAL training after a farewell bubble bath with her lover, a fellow Navy officer named Royce (Jason Beghe).

Now come the scenes from the movie that stay in the memory, as O’Neil joins a group of trainees in a regime of great rigor and uncompromising discomfort. The shivering, soaking wet, would-be SEALS stand endlessly while holding landing rafts over their heads, they negotiate obstacle courses, they march and run and crawl, they are covered with wet, cold mud, and then they do it all over again.

There is a bell next to the parade ground. Ring it, and you can go home. “I always look for one quitter on the first day,” barks Master Chief Urgayle (Viggo Mortensen), “and that day doesn’t stop until I get it.” He gets it, but not from O’Neil.

Urgayle is an intriguing character, played by Mortensen to suggest depths and complications. In an early scene he is discovered reading a novel by J.M. Coetzee, the dissident South African who is not on the Navy’s recommended reading list, and in an early scene he quotes a famous poem by D.H. Lawrence, both for its imagery (of a bird’s unattended death) and in order to freak out the trainees by suggesting a streak of subtle madness.

The training sequences are as they have to be: incredible rigors, survived by O’Neil. They are good cinema because Ridley Scott, the director, brings a documentary attention to them, and because Demi Moore, having bitten off a great deal here, proves she can chew it. The wrong casting in her role could have tilted the movie toward “Private Benjamin,” but Moore is serious, focused and effective.

Several of the supporting roles are well-acted and carefully written (by Danielle Alexandra and David Twohy). Anne Bancroft is brisk, smart and effective as the powerful U.S. senator. And consider Salem, the commanding officer, played by Scott Wilson. In an older movie, he would have been presented as an unreconstructed sexist. This movie is smart enough to know that modern officers have been briefed on the proper treatment of female officers, and that whatever their private views they know enough about military regulations and the possibility of disciplinary hearings that they try to go by the book.

Salem makes some seemingly helpful remarks about menstruation that are not quite called for (by the time a Navy woman gets to SEAL training, she has undoubtedly mastered the management of her period). But neither he nor Master Chief Urgayle are the enemy: They are meant to represent the likely realities a woman might face, not artificial movie villains.

There is a villain in the film. I will not reveal the details, although after the film is over you may find yourself asking, as I did, whether the villainous acts were inspired more by politics and corruption, or by the demands of the plot.

The plot also rears its head rather noticeably in the closing scenes, when the SEAL group finds itself in a situation much more likely to occur in a movie than in life. There is a battle sequence that is choreographed somewhat uncertainly by Scott, so that we cannot quite understand where everyone is or what is possible, and as a result the SEALS come across as not particularly competent. But by now we’re into movie payoff time, where the documentary conviction of the earlier scenes must give way to audience satisfaction.

Demi Moore remains one of the most venturesome of current stars, and although her films do not always succeed, she shows imagination in her choice of projects. It is also intriguing to watch her work with the image of her body. The famous pregnant photos on the cover of Vanity Fair can be placed beside her stripper in “Striptease,” her executive in “Disclosure” and the woman in “Indecent Proposal” who has to decide what a million dollars might purchase; all of these women, and now O’Neil, test the tension between a woman’s body and a woman’s ambition and will.

“G.I. Jane” does it most obviously, and effectively.