Robert Bresson‘s films are often about people confronting certain despair. His subject is how they try to prevail in the face of unbearable circumstances. His plots are not about whether they succeed, but how they endure. He tells these stories in an unadorned style, without movie stars, special effects, contrived thrills and elevated tension. His films, seemingly devoid of audience-pleasing elements, hold many people in a hypnotic grip. There are no “entertainment values” to distract us, only the actual events of the stories themselves. They demonstrate how many films contain only diversions for the eyes and mind, and use only the superficial qualities of their characters.

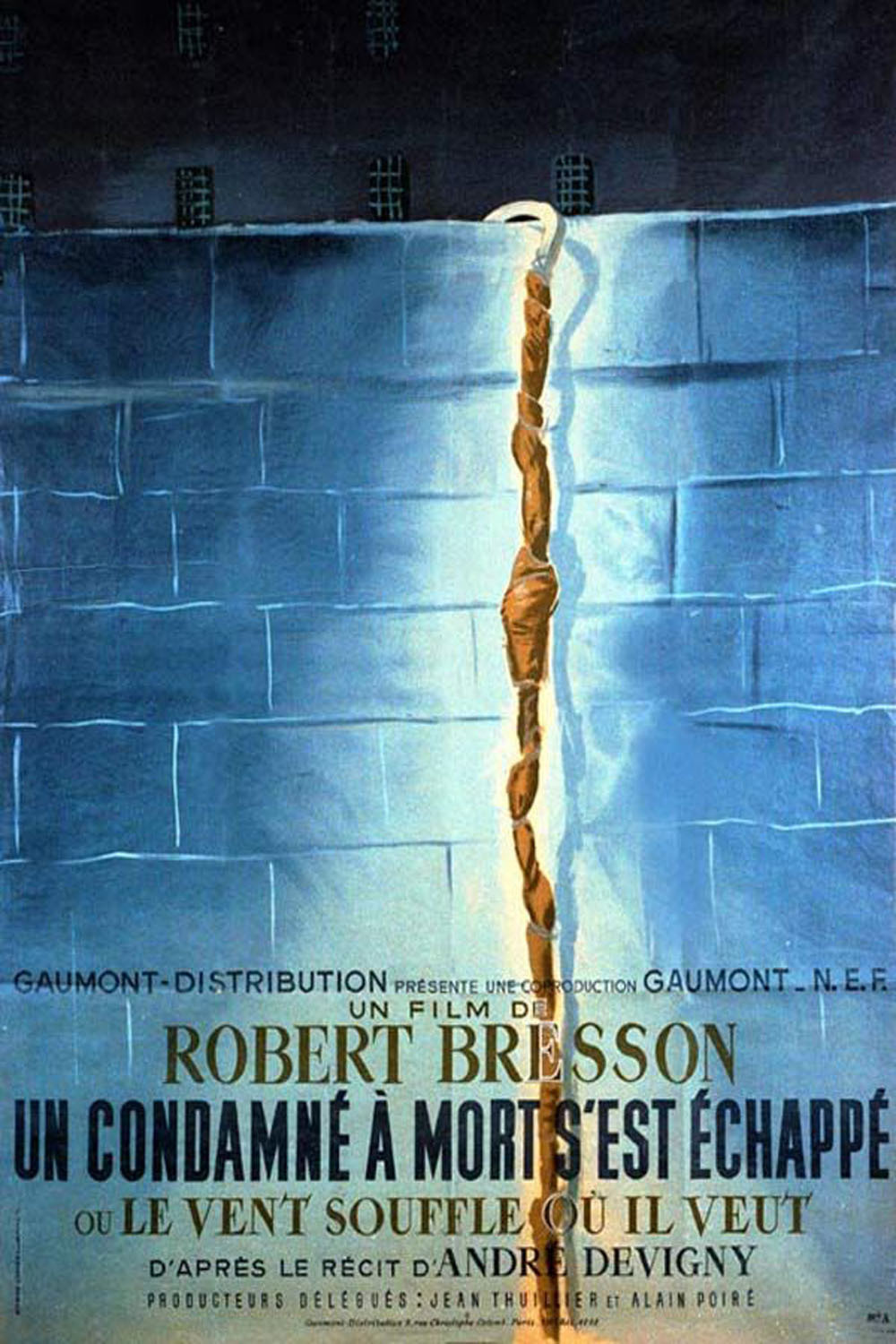

Consider “A Man Escaped” (1956). Here is a movie about a man condemned to death in 1943 in Montluc, a Nazi prison camp in Lyon, inside German-occupied France. In a shot that comes even before the titles, we learn that 7,000 men were killed there during the war. Then we meet the captured Resistance fighter Fontaine (François Leterrier), who has every reason to believe he will be one of them. The character is based on a postwar memoir by André Devigny, who escaped from Montluc on the very day he was scheduled to die.

If you saw this man sit on his bunk and stare at the wall, or hold his head in his hands, you would not blame him. What are his options? His cell is small, the walls and door are thick, the prison walls are high, the Nazi guards are outside. He is in solitary confinement most of the day, although sometimes he can tap out messages in a code, or secretly exchange notes during washing-up time. During the period of his confinement another man he has “met” this way is shot trying to escape.

Fontaine’s method is to use Bresson’s own method: The close scrutiny of salient details. In his films there are no “beauty shots.” No effects. No emphasis on the physical appearances of the actors. No fancy zooms or other shots that call attention. He uses the basic vocabulary of long, medium, close and insert shots, to tell what needs to be told about every scene. No shock cutaways. Reality-based, calm editing.

In this way, we watch Fontaine examine his cell. We know it as well as he does. We see how he stands on a shelf to look out a high, barred window. We see how the food plates enter and leave, and how the guards can see him through a peep hole. We see the routine as prisoners are marched to morning wash-up.

What we don’t see much of are the Nazi guards. Their figures appear in some shots, of course, but no point is made of them. None becomes a notable character. None has a name. Dialogue is disembodied. There are none of the usual clichés about the sadistic guard or the friendly guard. Even few of the other prisoners become very familiar to us; Fontaine sees them in passing. Although men are killed in the prison, it doesn’t happen onscreen. No ominous set-ups. Just off-screen sounds.

Therefore most of what happens takes place in Fontaine’s cell, as it must. By looking intently at every detail, Fontaine devises a way to get through the door, and then, he hopes, get over the wall. I won’t tell you what he does, which is what the movie is largely about. He doesn’t attempt his escape alone, but I won’t describe the other man, except to observe that Fontaine feels he must either try to bring him along or kill him. By trusting him, Bresson has Fontaine demonstrate a faith in a fellow human that is central to what he has to say in the film. Indeed, if Fontaine had not brought him along, it’s a good question whether his escape could succeed.

François Leterrier, playing Fontaine, is a man of ordinary appearance. Bresson did not choose to work with stars. Indeed, many stars might have been unhappy with his way of describing actors as “models.” Their role in a Bresson film is to embody a character, perform the physical actions, look plausible, and not draw undue attention. He wanted no “acting.” Whatever an actor did in bringing style or eccentricity to a role was unnecessary. It was all about the fact of the character, his situation and his behavior. Yes, we all love movie stars. But to some degree every shot they’re in is about them. They don’t get called back if nobody notices them. That’s why even extras dream of little bits of “business.” In theory, you should be able to see a Bresson film, go to dinner with the actor two days later, and not recognize him.

This has been an unusual movie review, mostly describing what doesn’t happen. Is the film therefore a static bore? Few films have seemed more absorbing to me. A man will die, or escape. Here is his cell. He has the desire. He uses his mind. We follow him every second of the way. There is a sparse narration, presumably based on André Devigny’s original book, but it describes only what actually happens and expresses no abstract thinking.

Watching a film like “A Man Escaped” is like a lesson in the cinema. It teaches by demonstration all the sorts of things that are not necessary in a movie. By implication, it suggests most of the things we’re accustomed to are superfluous. I can’t think of a single unnecessary shot in “A Man Escaped.”

If you removed the unnecessary shots from, say, Michael Bay’s “Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen,” you would be left with two much shorter films: (1) a montage of the special effects action, which is all some people are interested in; (2) a montage of plot points and essential explanatory dialogue, which would be much shorter than (1). The entire film is a smash-up between those two little films.

What have you learned at the end of the Bay film? Nothing, because the characters and the robots are flatly impossible. There may be value in overcooked hyperaction, and I’m not saying there isn’t. I’ve hugely enjoyed some action films for what they were. I admire “A Man Escaped” both for what it is, for what it isn’t, and for what I learned from it.

What was that? In a famous book by Paul Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film, three directors are considered: Yasujiro Ozu, Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer. Schrader feels transcendentalism is embedded in their work. Rather than involve ourselves in a deep discussion of transcendentalism, we might profitably start at the kindergarten level. The simplest parable for existentialism can be found in Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus. He takes only 120 pages, but we need only a paragraph:

Sisyphus was a man condemned to spend his life pushing a stone up a mountain, and seeing it roll back down again. At the bottom of the mountain, I suggest, is death. Pushing the stone is life. It is tempting to give up on the bloody stone, but Camus (also a supporter of the Resistance) said that it was necessary to revolt. In Montluc, 7,000 men died, but Fontaine did not agree he need be one of them. Even if he were crushed by the stone rolling downhill over him, at least he tried. It is probably relevant to this film that Bresson himself was a member of the Resistance, and was imprisoned by the Nazis.

“A Man Escaped” is streaming on Hulu.

Ebert’s Great Movies Collection also includes Bresson’s “Pickpocket,” “Diary of a Country Priest” and “Au Hasard Balthazar.” And, for that matter, Dreyer’s “Ordet” and “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” and Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal,” “Through a Glass Darkly,” “The Silence,” “Winter Light” “Persona,” “Cries and Whispers” and “Fanny and Alexander.”