She is a school mistress, he is a butcher, their everyday lives obscure great loneliness, and their ideas about sex are peculiarly skewed. They should never have met each other. When they do start to spend time together, their relationship seems ordinary and uneventful, but it sets terrible engines at work in the hiding places of their beings. It is clear by the end of the film how this friendship has set loose violent impulses in the butcher — but what many viewers miss is how the school mistress is also transformed, in a way no less terrible.

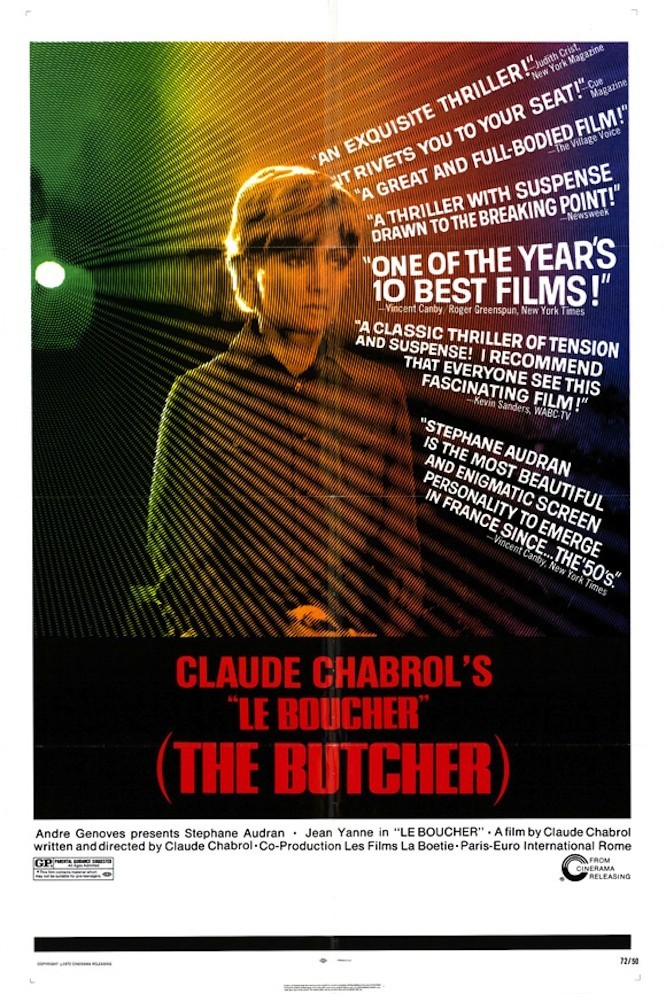

Claude Chabrol’s “Le Boucher” (1970) takes place in the tranquil French village of Tremolat, and like almost all of his films, begins and ends with a shot of a river, and includes at least one meal. It seems a pleasant district, if it were not for the ominous stirrings and sudden hard chords on the soundtrack. It is a movie in which three victims are carved up offscreen, but the only violence visible to us is psychic, and deals with the characters’ twists and needs.

There is no great mystery about the identity of the killer; it must be Popaul the butcher, because no other plausible suspects are brought onscreen. We know it, the butcher knows it, and at some point, Miss Helene, the school mistress, certainly knows it. Is it when she finds the cigarette lighter he dropped, or does she begin to suspect even earlier?

The movie’s suspense involves the haunting dance that the two characters perform around the fact of the butcher’s guilt. Will he kill her, too? Does she want to be killed? No, not at all, but perhaps she wants to get teasingly close to being killed; perhaps she is fascinated by the butcher’s savagery.

During a class trip to the nearby Lascaux caves and their wall paintings, she speaks approvingly of Cro-Magnon Man. His instincts and intelligence were human, she says. A child asks: What if he came back now, the Cro-Magnon? What would he do? Miss Helene replies: Maybe he would adapt and live among us. Or maybe he would die. Is she thinking of the butcher?

Perhaps even at their first meeting, she was fascinated by the danger she sensed in Popaul (Jean Yanne). Miss Helene (Stephane Audran) is seated next to him at the wedding of her fellow teacher, and the first thing she sees him do is carve a roast. Notice how avidly she follows the movement of the knife, how eagerly she takes her slice, how she begins to eat before anyone else has been served. And notice too how she seems curiously happy, as if she has found something she was looking for; she is intense and alert to the presence of the butcher.

As the wedding ends and he walks her home to her rooms above the school, Chabrol gives us a remarkable unbroken shot, three minutes and 46 seconds in duration. They walk through the entire village, past men in cafes and boys at play. She takes out a Gauloise and lights up, and he asks: “You smoke in the street?” She not only smokes, she smokes with an attitude, holding the cigarette in her mouth, Belmondo-style, even while she talks. She is sending a message of female dominance and mystery to Popaul. Later, when he visits her, he sits on a chair that makes him lower than her, like one of her students.

She has been in Tremolat for three years. She has never married; 10 years before, she had an unhappy affair, and has decided to do without men. He can talk of little but his 15 years in the French Army. He served in Algiers and Indochina, and he hints of indescribable brutality that he witnessed. He brings her a joint of lamb, wrapped in tissue like a bouquet, and they spend time together. News arrives from day to day about bodies found in the woods, and the police are everywhere. On the day of the trip to the caves, Miss Helene and her students rest on a ledge to eat their lunches, and a drop of blood falls on one little girl’s bread. It is the blood of the latest victim — the bride in the opening scene.

As she discovers the body, Miss Helene also finds a distinctive lighter she has given Popaul. We follow her response closely, trying to guess what she’s thinking. She puts the lighter in a drawer, and tells the police she found no clues. Soon after, Popaul comes over with a jar of cherries marinated in brandy. They’re the best I ever had, she says, before she has eaten one. Our suspense is matched by our curiosity: Does she think she is sitting alone with a killer? Does he wonder if she knows? Eventually she asks for a light. He pulls out a lighter just like the one she gave him. She begins to laugh.

Smoking is a motif in the movie. We never see him smoking until she does. When and why he smokes is always important. In that scene he glances at an ashtray but deliberately doesn’t smoke, for example, until she asks for a light, and he can produce the lighter. Another motif, Hitchcockian, is her blond hair; we see it many times from behind, once with an ominous push-in, and then at the end of the movie there is a matching push to her face. Another match: On his first and last visits to the school, his face is framed in the same window.

“Le Boucher” has us always thinking. What do they know, what do they think, what do they want? The film builds to an emotional and physical climax which I will not describe, except to urge you to pay particular attention to a sequence toward the end where Chabrol cuts from her face to his. Popaul’s face shows desperate devotion and need. What does her face show? Is it triumph? Pity? Fear? A kind of sexual fulfillment? Interpret that expression, and you have the key to her feeling. It sure isn’t concern.

Stephane Audran, who was married to Chabrol from 1964 to 1982, has one of those faces like Deneuve or Moreau: The beauty is classic, but can be undercut by glimpses of deep and peculiar need. Audran in that last sequence is like Deneuve in “Belle de Jour,” impassive in the face of enormous inner excitement. Audran worked with Chabrol in “The Champagne Murders” (1966), “Les Biches” (1968) and “Le Femme Infidele” (1969), and was in “Les Cousins” (1959), which was one of the founding films of the French New Wave.

Chabrol, born in 1930, was like Godard and Truffaut a movie critic writing for Cahiers du Cinema, the voice of the auteur movement. He has outlasted many of his contemporaries and outproduced all of them, making more than 50 films; “Merci Pour Le Chocolat” (2000) was about a bourgeois family poisoning itself literally and figuratively, and his “La Fleur du Mal” (2003) is about another bourgeois family, rotten to the core. His good or great films make a long list, which should include four collaborations with Isabelle Huppert: “Violette Noziere” (1978), “Madame Bovary” (1991), “La Ceremonie” (1995), “Merci Pour Le Chocolat.” Her face, like Audran’s, is capable of maddening passivity — a mask for ominous and alarming thoughts. Both actresses have that rare ability to compel us to wonder what in the hell they are thinking.

Sample the reviews of “Le Boucher,” and you’ll find it described as a film about a savage murderer and the school mistress who doesn’t know the danger she’s in. This completely misses the point. It’s not that the point is hard to find — Chabrol is very clear about his purpose — but that we’ve been hammered down by so many slack-witted thrillers that we’ve learned to assume that the killer is the villain and the woman is the victim.

Popaul is a killer, all right, but is he also a victim? Was he traumatized by the army, by blood and meat? Is he driven to kill because Miss Helene, who he idolizes beyond all measuring, remains cool and distant, tantalizingly unavailable? Some think that Chabrol even blames Miss Helene for the crimes; if she’d only slept with Popaul, his savage impulse would have been diverted.

But it’s not that simple. (1) He is attracted to her because she is unavailable, and it’s her butchy walk through the village, smoking that cigarette, that seals his fate. (2) Since (as I believe) she is excited in a perverse, obscure way by the danger he represents, does he sense that? Are his killings in some measure offerings, as a cat will lay a bird at the feet of its owner?

So much goes unsaid between these two people. So much is guessed or hinted. They’re a pair, all right, and she senses it at the wedding feast. They don’t fit in any ordinary romantic or matrimonial way, but what happens in this movie happens because of them as a couple. If you bring enough empathy to her character, you can read that final scene more deeply. It is a sex scene. They don’t touch, but then they never did.