“What kind of town is this?” Wyatt Earp asks on his first

night in Tombstone. “A man can’t get a shave without gettin’ his head blowed

off.” He gets up out of the newfangled barber’s chair at the Bon Ton Tonsorial

Parlor and climbs through the second-story window of a saloon, his face still

half lathered, to konk a gun-toting drunk on the head and drag him out by the

heels.

Earp

(Henry Fonda) already knows what kind of town it is. In the opening scenes of

John Ford’s greatest Western, “My Darling Clementine” (1946), he and his

brothers are driving cattle east to Kansas. Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan leave

their kid brother James in charge of the herd and go into town for a shave and

a beer. As they ride down the main street of Tombstone, under a vast and

lowering evening sky, gunshots and raucous laughter are heard in the saloons,

and we don’t have to ask why the town has the biggest graveyard west of the

Rockies.

Ford’s

story reenacts the central morality play of the Western. Wyatt Earp becomes the

town’s new marshal, there’s a showdown between law and anarchy, the law wins

and the last shot features the new schoolmarm–who represents the arrival of

civilization. Most Westerns put the emphasis on the showdown. “My Darling

Clementine” builds up to the legendary gunfight at the OK Corral, but it is

more about everyday things–haircuts, romance, friendship, poker and illness.

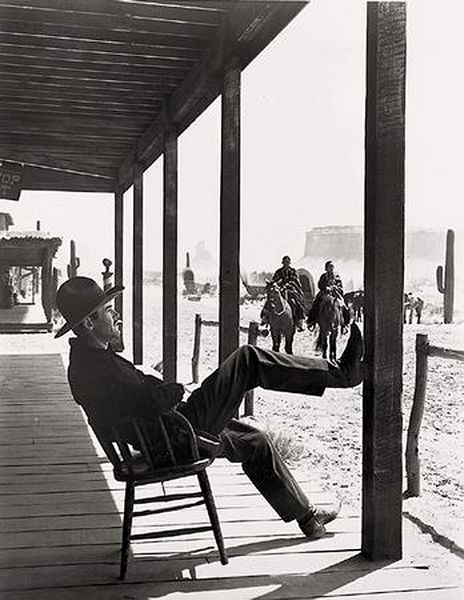

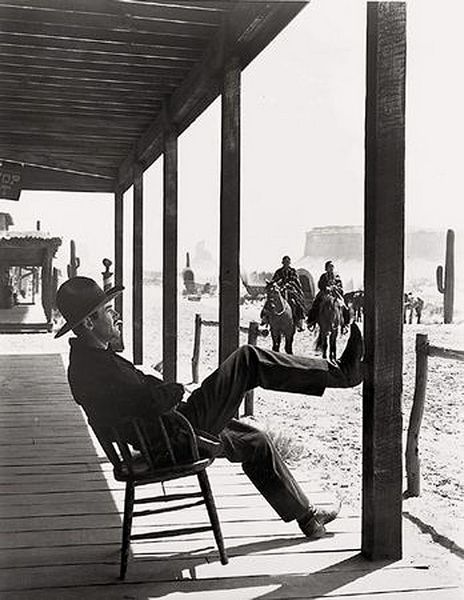

At

the center is Henry Fonda’s performance as Wyatt Earp. He’s usually shown as a

man of action, but Fonda makes him the new-style Westerner, who stands up when

a woman comes into the room and knows how to carve a chicken and dance a reel.

Like a teenager, he sits in a chair on the veranda of his office, tilts back to

balance on the back legs and pushes off against a post with one boot and then

the other. He’s thinking of Clementine, and Fonda shows his happiness with body

language.

Earp

has accepted the marshal’s badge because when he and his brothers returned to

their herd, they found the cattle rustled and James dead. There is every reason

to believe the crime was committed by Old Man Clanton (Walter Brennan) and his “boys”

(grown, bearded and mean). An early scene ends with Clanton baring his teeth

like an animal showing its fangs. Earp buries James in a touching scene. (“You

didn’t get much of a chance, did you, James?”) Then, instead of riding into

town and shooting the Clantons, he tells the mayor he’ll become the new

marshal. He wants revenge, but legally.

The

most important relationship is between Earp and Doc Holliday (Victor Mature),

the gambler who runs Tombstone but is dying of tuberculosis. They are natural

enemies, but a quiet, unspoken regard grows up between the two men, maybe

because Earp senses the sadness at Holliday’s core. Holliday’s rented room has

his medical diploma on the wall and his doctor’s bag beneath it, but he doesn’t

practice anymore. Something went wrong back East, and now he gambles for a

living, and drinks himself into oblivion. His lover is a prostitute, Chihuahua

(Linda Darnell), and he talks about leaving for Mexico with her. But as he

coughs up blood, he knows what his prognosis is.

The

marshal’s first showdown with Holliday is a classic Ford scene. The saloon

grows quiet when Doc walks in, and the bar clears when he walks up to it. He

tells Earp, “Draw!” Earp says he can’t–doesn’t have a gun. Doc calls for a

gun, and a man down the bar slides him one. Earp looks at the gun, and says, “Brother

Morg’s gun. The other one, the good-lookin’ fellow–that’s my brother, Virg.”

Doc registers this information and returns his own gun to its holster. He

realizes Earp’s brothers have the drop on him. “Howdy,” says Doc. “Have a

drink.”

Twice

Doc tells someone to get out of town, and twice Earp reminds him that’s the

marshal’s job. Although the Clantons are the first order of business, Doc and

Earp seem headed for a showdown. Yet they have a scene together that is one of

the strangest and most beautiful in all of John Ford’s work. A British actor

(Alan Mowbray) has come to town to put on a play, and when he doesn’t show up

at the theater, Earp and Holliday find him in the saloon, on top of a table,

being tormented by the Clantons. The actor begins Hamlet’s famous soliloquy,

but is too drunk and frightened to continue. Doc Holliday, from memory,

completes the speech, and could be speaking of himself: “ … but that the

dread of something after death, the undiscovered country from whose bourn no

traveler returns, puzzles the will … .”

The

gentlest moments in the movie involve Earp’s feelings for Clementine (Cathy

Downs), who arrives on the stage from the East, looking for “Dr. John Holliday.”

She is the girl Doc left behind. Earp, sitting outside the hotel, rises quickly

to his feet as she gets out of the stage, and his movements show that he’s in

awe of this graceful vision. Clementine has been seeking Doc all over the West,

we learn, and wants to bring him home. Doc tells her to get out of town. And

Chihuahua monitors the situation jealously.

Clementine

is packed to go the next morning when the marshal, awkward and shy, asks her to

join him at the church service and dance. They walk in stately procession down

the covered boardwalk, while Ford’s favorite hymn plays: “Shall We Gather at

the River?” When the fiddler strikes up, Wyatt and Clementine dance–he clumsy

but enthusiastic, and with great joy. This dance is the turning point of the

movie, and marks the end of the Old West. There are still shots to be fired,

but civilization has arrived.

The

legendary gunfight at the OK Corral has been the subject of many films,

including “Frontier Marshal” (1939), “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” (1957), “Tombstone”

(1993, with Val Kilmer’s brilliant performance as Doc) and “Wyatt Earp” (1994).

Usually the gunfight is the centerpiece of the film. Here it plays more like

the dispatch of unfinished business; Ford doesn’t linger over the violence.

There

is the quiet tenseness in the marshal’s office as Earp prepares to face the

Clantons, who’ve shouted their challenge that they’d be waiting for him at the

corral. Earp’s brothers are with him, because this is “family business.” Earp

turns down other volunteers, but when Doc turns up, he lets him take part,

because Doc has family business, too (one of the Clanton boys has killed

Chihuahua). Under the merciless clear sky of a desert dawn, in silence except

for far-off horse whinnies and dog barks, the men walk down the street and take

care of business.

John

Ford (1895-1973) was, many believe, the greatest of all American directors.

Certainly he did more than any other to document the passages of American

history. For him, a Western was not quite such a “period film” as it would be

for later directors. He shot on location in the desert and prairie, his cast

and crew living as if they were on a cattle drive, eating out of the

chuckwagon, sleeping in tents. He filmed “My Darling Clementine” in his beloved

Monument Valley, on the Arizona-Utah border.

He

made dozens of silent Westerns, met the real Wyatt Earp on the set of a movie

and heard the story of the OK Corral directly from him (even so, history tells

a story much different from this film). Ford worked repeatedly with the same

actors (his “stock company”) and it is interesting that he chose Fonda rather

than John Wayne, his other favorite, for Wyatt Earp. Maybe he saw Wayne as the

embodiment of the Old West, and the gentler Fonda as one of the new men who

would tame the wilderness.

“My

Darling Clementine” must be one of the sweetest and most good-hearted of all

Westerns. The giveaway is the title, which is not about Wyatt or Doc or the

gunfight, but about Clementine, certainly the most important thing to happen to

Marshal Earp during the story. There is a moment, soon after she arrives, when

Earp gets a haircut and a quick spray of perfume at the Bon Ton Tonsorial

Parlor. Clem stands close to him and says she loves “the scent of the desert

flowers.” “That’s me,” says Earp. “Barber.”