“It wasn’t a message that stirred the audiences, nor was it a great performance…they were aroused by pure film.”

So Alfred Hitchcock told Francois Truffaut about “Psycho,” adding that it “belongs to filmmakers, to you and me.” Hitchcock deliberately wanted “Psycho” to look like a cheap exploitation film. He shot it not with his usual expensive feature crew (which had just finished “North by Northwest”) but with the crew he used for his television show. He filmed in black and white. Long passages contained no dialogue. His budget, $800,000, was cheap even by 1960 standards; the Bates Motel and mansion were built on the back lot at Universal. In its visceral feel, “Psycho” has more in common with noir quickies like “Detour” than with elegant Hitchcock thrillers like “Rear Window” or “Vertigo.”

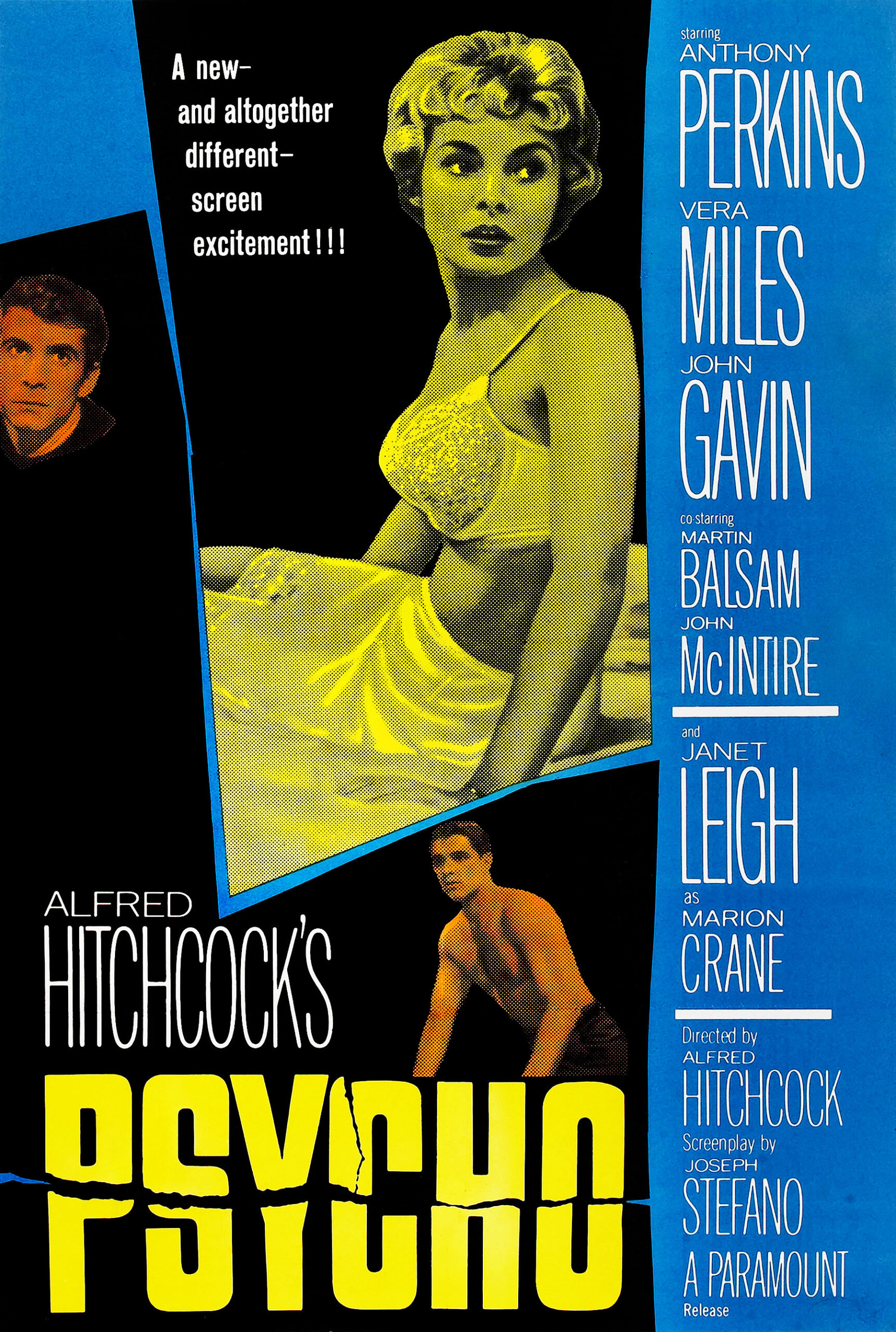

Yet no other Hitchcock film had a greater impact. “I was directing the viewers,” the director told Truffaut in their book-length interview. “You might say I was playing them, like an organ.” It was the most shocking film its original audience members had ever seen. “Do not reveal the surprises!” the ads shouted, and no moviegoer could have anticipated the surprises Hitchcock had in store–the murder of Marion (Janet Leigh), the apparent heroine, only a third of the way into the film, and the secret of Norman’s mother. “Psycho” was promoted like a William Castle exploitation thriller. “It is required that you see ‘Psycho’ from the very beginning!” Hitchcock decreed, explaining, “the late-comers would have been waiting to see Janet Leigh after she had disappeared from the screen action.”

These surprises are now widely known, and yet “Psycho” continues to work as a frightening, insinuating thriller. That’s largely because of Hitchcock’s artistry in two areas that are not as obvious: The setup of the Marion Crane story, and the relationship between Marion and Norman (Anthony Perkins). Both of these elements work because Hitchcock devotes his full attention and skill to treating them as if they will be developed for the entire picture.

The setup involves a theme that Hitchcock used again and again: The guilt of the ordinary person trapped in a criminal situation. Marion Crane does steal $40,000, but still she fits the Hitchcock mold of an innocent to crime. We see her first during an afternoon in a shabby hotel room with her divorced lover, Sam Loomis (John Gavin). He cannot marry her because of his alimony payments; they must meet in secret. When the money appears, it’s attached to a slimy real estate customer (Frank Albertson) who insinuates that for money like that, Marion might be for sale. So Marion’s motive is love, and her victim is a creep.

This is a completely adequate setup for a two-hour Hitchcock plot. It never for a moment feels like material manufactured to mislead us. And as Marion flees Phoenix on her way to Sam’s home town of Fairvale, Calif., we get another favorite Hitchcock trademark, paranoia about the police. A highway patrolman (Mort Mills) wakes her from a roadside nap, questions her, and can almost see the envelope with the stolen money. She trades in her car for one with different plates, but at the dealership she’s startled to see the same patrolman parked across the street, leaning against his squad car, arms folded, staring at her. Every first-time viewer believes this setup establishes a story line the movie will follow to the end.

Frightened, tired, perhaps already regretting her theft, Marion drives closer to Fairvale but is slowed by a violent rainstorm. She pulls into the Bates Motel, and begins her short, fateful association with Norman Bates. And here again Hitchcock’s care with the scenes and dialog persuades us that Norman and Marion will be players for the rest of the film.

He does that during their long conversation in Norman’s “parlor,” where savage stuffed birds seem poised to swoop down and capture them as prey. Marion has overheard the voice of Norman’s mother speaking sharply with him, and she gently suggests that Norman need not stay here in this dead end, a failing motel on a road that has been bypassed by the new interstate. She cares about Norman. She is also moved to rethink her own actions. And he is touched. So touched, he feels threatened by his feelings. And that is why he must kill her.

When Norman spies on Marion, Hitchcock said, most audience members read it as Peeping Tom behavior. Truffaut observed that the film’s opening, with Marion in a bra and panties, underlines the later voyeurism. We have no idea murder is in store.

Seeing the shower scene today, several things stand out. Unlike modern horror films, “Psycho” never shows the knife striking flesh. There are no wounds. There is blood, but not gallons of it. Hitchcock shot in black and white because he felt the audience could not stand so much blood in color (the 1998 Gus Van Sant remake specifically repudiates that theory). The slashing chords of Bernard Herrmann’s soundtrack substitute for more grisly sound effects. The closing shots are not graphic but symbolic, as blood and water spin down the drain, and the camera cuts to a closeup, the same size, of Marion’s unmoving eyeball. This remains the most effective slashing in movie history, suggesting that situation and artistry are more important than graphic details.

Perkins does an uncanny job of establishing the complex character of Norman, in a performance that has become a landmark. Perkins shows us there is something fundamentally wrong with Norman, and yet he has a young man’s likability, jamming his hands into his jeans pockets, skipping onto the porch, grinning. Only when the conversation grows personal does he stammer and evade. At first he evokes our sympathy as well as Marion’s.

The death of the heroine is followed by Norman’s meticulous mopping-up of the death scene. Hitchcock is insidiously substituting protagonists. Marion is dead, but now (not consciously but in a deeper place) we identify with Norman–not because we could stab someone, but because, if we did, we would be consumed by fear and guilt, as he is. The sequence ends with the masterful shot of Bates pushing Marion’s car (containing her body and the cash) into a swamp. The car sinks, then pauses. Norman watches intently. The car finally disappears under the surface.

Analyzing our feelings, we realize we wanted that car to sink, as much as Norman did. Before Sam Loomis reappears, teamed up with Marion’s sister Lila (Vera Miles) to search for her, “Psycho” already has a new protagonist: Norman Bates. This is one of the most audacious substitutions in Hitchcock’s long practice of leading and manipulating us. The rest of the film is effective melodrama, and there are two effective shocks. The private eye Arbogast (Martin Balsam) is murdered, in a shot that uses back-projection to seem to follow him down the stairs. And the secret of Norman’s mother is revealed.

For thoughtful viewers, however, an equal surprise is still waiting. That is the mystery of why Hitchcock marred the ending of a masterpiece with a sequence that is grotesquely out of place. After the murders have been solved, there is an inexplicable scene during which a long-winded psychiatrist (Simon Oakland) lectures the assembled survivors on the causes of Norman’s psychopathic behavior. This is an anticlimax taken almost to the point of parody.

If I were bold enough to reedit Hitchcock’s film, I would include only the doctor’s first explanation of Norman’s dual personality: “Norman Bates no longer exists. He only half existed to begin with. And now, the other half has taken over, probably for all time.” Then I would cut out everything else the psychiatrist says, and cut to the shots of Norman wrapped in the blanket while his mother’s voice speaks (“It’s sad when a mother has to speak the words that condemn her own son…”). Those edits, I submit, would have made “Psycho” very nearly perfect. I have never encountered a single convincing defense of the psychiatric blather; Truffaut tactfully avoids it in his famous interview.

What makes “Psycho” immortal, when so many films are already half-forgotten as we leave the theater, is that it connects directly with our fears: Our fears that we might impulsively commit a crime, our fears of the police, our fears of becoming the victim of a madman, and of course our fears of disappointing our mothers.