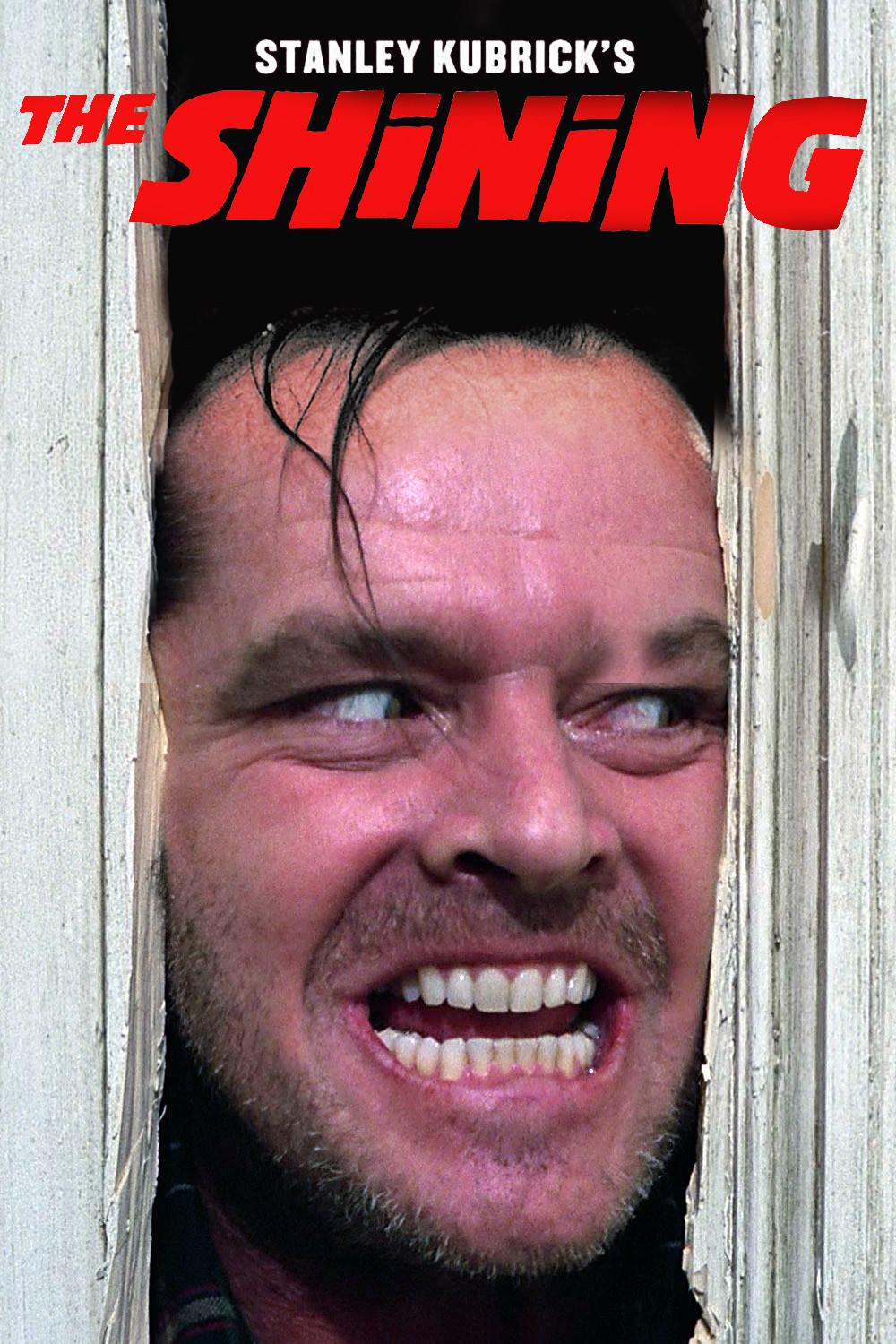

Stanley Kubrick’s cold and frightening “The Shining”

challenges us to decide: Who is the reliable observer? Whose idea of events can

we trust? In the opening scene at a job interview, the characters seem reliable

enough, although the dialogue has a formality that echoes the small talk on the

space station in “2001.” We meet Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), a

man who plans to live for the winter in solitude and isolation with his wife

and son. He will be the caretaker of the snowbound Overlook Hotel. His employer

warns that a former caretaker murdered his wife and two daughters, and

committed suicide, but Jack reassures him: “You can rest assured, Mr.

Ullman, that’s not gonna happen with me. And as far as my wife is concerned,

I’m sure she’ll be absolutely fascinated when I tell her about it. She’s a

confirmed ghost story and horror film addict.”

Do

people talk this way about real tragedies? Will his wife be absolutely

fascinated? Does he ever tell her about it? Jack, wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall)

and son Danny (Danny Lloyd) move into the vast hotel just as workers are

shutting it down for the winter; the chef, Dick Hallorann (Scatman Crothers)

gives them a tour, with emphasis on the food storage locker (“You folks

can eat up here a whole year and never have the same menu twice”). Then

they’re alone, and a routine begins: Jack sits at a typewriter in the great

hall, pounding relentlessly at his typewriter, while Wendy and Danny put

together a version of everyday life that includes breakfast cereal, toys and a

lot of TV. There is no sense that the three function together as a loving

family.

Danny:

Is he reliable? He has an imaginary friend named Tony, who speaks in a lower

register of Danny’s voice. In a brief conversation before the family is left

alone, Hallorann warns Danny to stay clear of Room 237, where the violence took

place, and he tells Danny they share the “shining,” the psychic gift

of reading minds and seeing the past and future. Danny tells Dick that Tony

doesn’t want him to discuss such things. Who is Tony? “A little boy who

lives in my mouth.”

Tony

seems to be Danny’s device for channeling psychic input, including a shocking

vision of blood spilling from around the closed doors of the hotel elevators.

Danny also sees two little girls dressed in matching outfits; although we know

there was a two-year age difference in the murdered children, both girls look

curiously old. If Danny is a reliable witness, he is witness to specialized

visions of his own that may not correspond to what is actually happening in the

hotel.

That

leaves Wendy, who for most of the movie has that matter-of-fact banality that

Shelley Duvall also conveyed in Altman’s “3 Women.” She is a

companion and playmate for Danny, and tries to cheer Jack until he tells her,

suddenly and obscenely, to stop interrupting his work. Much later, she

discovers the reality of that work, in one of the movie’s shocking revelations.

She is reliable at that moment, I believe, and again toward the end when she

bolts Jack into the food locker after he turns violent.

But

there is a deleted scene from “The Shining” (1980) that casts Wendy’s

reliability in a curious light. Near the end of the film, on a frigid night,

Jack chases Danny into the labyrinth on the hotel grounds. His son escapes, and

Jack, already wounded by a baseball bat, staggers, falls and is seen the next

day, dead, his face frozen into a ghastly grin. He is looking up at us from

under lowered brows, in an angle Kubrick uses again and again in his work. Here

is the deletion, reported by the critic Tim Dirks: “A two-minute

explanatory epilogue was cut shortly after the film’s premiere. It was a

hospital scene with Wendy talking to the hotel manager; she is told that

searchers were unable to locate her husband’s body.”

If

Jack did indeed freeze to death in the labyrinth, of course his body was found

— and sooner rather than later, since Dick Hallorann alerted the forest

rangers to serious trouble at the hotel. If Jack’s body was not found, what

happened to it? Was it never there? Was it absorbed into the past, and does

that explain Jack’s presence in that final photograph of a group of hotel

partygoers in 1921? Did Jack’s violent pursuit of his wife and child exist

entirely in Wendy’s imagination, or Danny’s, or theirs?

The

one observer who seems trustworthy at all times is Dick Hallorann, but his

usefulness ends soon after his midwinter return to the hotel. That leaves us

with a closed-room mystery: In a snowbound hotel, three people descend into

versions of madness or psychic terror, and we cannot depend on any of them for

an objective view of what happens. It is this elusive open-endedness that makes

Kubrick’s film so strangely disturbing.

Yes,

it is possible to understand some of the scenes of hallucination. When Jack

thinks he is seeing other people, there is always a mirror present; he may be

talking with himself. When Danny sees the little girls and the rivers of blood,

he may be channeling the past tragedy. When Wendy thinks her husband has gone

mad, she may be correct, even though her perception of what happens may be

skewed by psychic input from her son, who was deeply scarred by his father’s

brutality a few years earlier. But what if there is no body at the end?

Kubrick

was wise to remove that epilogue. It pulled one rug too many out from under the

story. At some level, it is necessary for us to believe the three members of

the Torrance family are actually residents in the hotel during that winter,

whatever happens or whatever they think happens.

Those

who have read Stephen King’s original novel report that Kubrick dumped many

plot elements and adapted the rest to his uses. Kubrick is telling a story with

ghosts (the two girls, the former caretaker and a bartender), but it isn’t a

“ghost story,” because the ghosts may not be present in any sense at

all except as visions experienced by Jack or Danny.

The

movie is not about ghosts but about madness and the energies it sets loose in

an isolated situation primed to magnify them. Jack is an alcoholic and child

abuser who has reportedly not had a drink for five months but is anything but a

“recovering alcoholic.” When he imagines he drinks with the imaginary

bartender, he is as drunk as if he were really drinking, and the imaginary

booze triggers all his alcoholic demons, including an erotic vision that turns

into a nightmare. We believe Hallorann when he senses Danny has psychic powers,

but it’s clear Danny is not their master; as he picks up his father’s madness

and the story of the murdered girls, he conflates it into his fears of another

attack by Jack. Wendy, who is terrified by her enraged husband, perhaps also

receives versions of this psychic output. They all lose reality together. Yes, there

are events we believe: Jack’s manuscript, Jack locked in the food storage room,

Jack escaping, and the famous “Here’s Johnny!” as he hatchets his way

through the door. But there is no way, within the film, to be sure with any

confidence exactly what happens, or precisely how, or really why.

Kubrick

delivers this uncertainty in a film where the actors themselves vibrate with

unease. There is one take involving Scatman Crothers that Kubrick famously

repeated 160 times. Was that “perfectionism,” or was it a mind game

designed to convince the actors they were trapped in the hotel with another

madman, their director? Did Kubrick sense that their dismay would be absorbed

into their performances?

“How

was it, working with Kubrick?” I asked Duvall 10 years after the

experience.

“Almost

unbearable,” she said. “Going through day after day of excruciating

work, Jack Nicholson’s character had to be crazy and angry all the time. And my

character had to cry 12 hours a day, all day long, the last nine months

straight, five or six days a week. I was there a year and a month. After all

that work, hardly anyone even criticized my performance in it, even to mention

it, it seemed like. The reviews were all about Kubrick, like I wasn’t

there.”

Like

she wasn’t there.

Also in Ebert’s Great Movies series at rogerebert.com: Kubrick’s

“Paths of Glory,” “Dr. Strangelove” and “2001: A Space

Odyssey.”