Godard. We all went to Jean-Luc Godard in the 1960s. We stood in the rain outside the Three Penny Cinema, waiting for the next showing of “Weekend” (1968). One year the New York Film Festival showed two of his movies, or was it three? One year at the Toronto festival Godard said, “The cinema is not the station. The cinema is the train.” Or perhaps it was the other way around. We nodded. We loved his films. As much as we talked about Tarantino after “Pulp Fiction,” we talked about Godard in those days. I remember a sentence that became part of my repertory: “His camera rotates 360 degrees, twice, and then stops and moves back in the other direction just a little_to show that it knows what it’s doing!”

And now the name Godard inspires a blank face from most filmgoers. Subtitled films are out. Art films are out. Self-conscious films are out. Films that test the edges of the cinema are out. Now it is all about the mass audience: It must be congratulated for its narrow tastes, and catered to. And yet, idly watching television as Aerosmith is inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, I reflect that if they can be resurrected from the ashes of more radical decades, then why not Godard?

I originally think to choose “Breathless” (1960), which fired an opening salvo of the French New Wave, had us all talking about “jump cuts,” and made Jean-Paul Belmondo a star. But there is a new DVD of “My Life to Live” (“Vivre Sa Vie”), from 1963. I slip it into the machine, and within five minutes I am so fascinated that I do not move, I do not stir, until it is over. This is a great movie, and I am not surprised to find Susan Sontag describing it as “one of the most extraordinary, beautiful, and original works of art that I know of.”

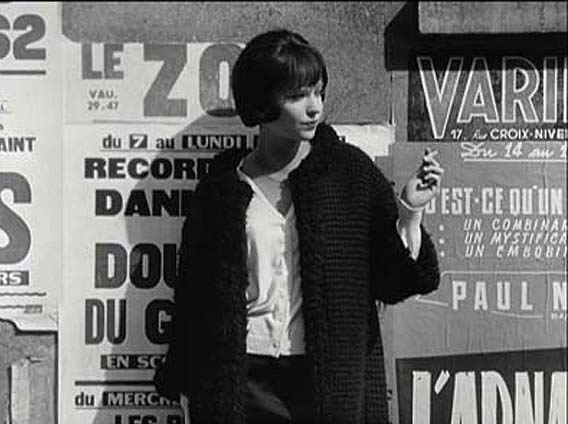

It tells the story of Nana, played by Anna Karina, who was Godard’s wife at the time. With her porcelain skin, her wary eyes, her helmet of shiny black hair, her chic outfits, always smoking, hiding her feelings, she is a young woman of Paris. The title shots show her in profile and full face, like mug shots, and we will be looking at her for the whole movie, trying to read her, for she reveals nothing willingly. Each shot begins with Michel Legrand music, which stops abruptly, to begin again with the next shot_as if to say, the music will try to explain, but fail. In the next shots we see her from behind, in a cafe, as she talks to a man, Paul. We learn he is her husband, that she has left him and their child, that she has vague plans to go into the movies.

Raoul Coutard, the cinematographer who worked side-by-side with Godard during this period, has his camera track back and forth, first behind Nana’s head, then Paul’s, their faces glimpsed in the mirror. “The film was made by sort of a second presence,” Godard said; the camera is not just a recording device but a looking device, that by its movements makes us aware that it sees her, wonders about her, glances first here and then there, exploring the space she occupies, speculating.

The movie is in 12 sections, each one with titles like an old-fashioned novel. She plays pinball. She works in a record store. She needs money. She tries to steal her flat key from the office of her concierge, but is caught and frog-marched to the street, her arm twisted behind her. She has no home and no money. Is this her fault, or fate? Why did she leave Paul? Has she no feelings for her child? The movie does not say. She is impassive. She goes to see a movie (Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” about a woman judged by men). She ditches the guy who bought her the ticket, and meets a guy in a bar who wants to take some pictures of her. She’s picked up by the cops_a dispute about a “dropped” 1,000-franc note. She goes to a street where prostitutes work. She lets a guy pick her up. She won’t let him kiss her.

The camera is right there. In the record store, it pans back and forth with Nana and a customer, then turns and looks out a window. In a bar, the camera starts to pan to the left and then glances back again. On the street with the hookers, the camera looks first down one side and then the other, slowing at a woman it finds intriguing. She meets Raoul, a pimp. “Give me a smile,” he says, as the camera holds them both in two-shot. She refuses, then smiles and exhales at the same time, and the camera turns away from Raoul and approaches her, suddenly interested, as she does. We are implicated. We are the camera, watching, wondering. The camera is not expressing a “style” but the way people look at other people.

Fmous shots. She smokes while a client embraces her, looking over his shoulder, eyes empty. Later Raoul inhales and kisses her, and she blows out his smoke. What is there to do in this Paris but hang out in bars, smoke, wish you had more money? Prostitution for her isn’t much more interesting than pinball. In France, prostitution is called “the life,” which gives another meaning to the title. There is a monotone Q&A conversation in which Raoul explains the rules of her new trade. Then the movie devolves into a crime story, and we are reminded that “Breathless” also ended in a violent shooting in the street, although in “My Life to Live,” the camera sees the violent moment and then_looks down! Down at the street, or at its feet. The film looks away from its own ending.

There is a scene in a cafe a little earlier, with Nana in conversation with the man at the next table, a philosopher (Brice Parain, apparently playing himself). He tells her the story of a man who runs away from danger, and then stops, paralyzed by the thought of how to put one foot in front of another. “The first time he thought,” observes the philosopher, “it killed him.”

If she thinks, will it kill her? We notice her openness, her curiosity, in talking to the old man. This from a woman who has been reluctant to reveal any thoughts or feelings, who has been all surface. We are reminded of a story Paul told earlier in the film, about a child who explained that if you take away the outside of a chicken, you have the inside, and if you take away the inside, you have the soul. Nana is all outside.

The film has no extra gestures. It regards with a level, interested gaze. The camera by its discipline discourages us from interpreting Nana’s life in a melodramatic way. There is that dry French logic, the way every statement seems prefaced by an inaudible “of course.” Curious, then, how moving Anna Karina makes Nana. She waits, she drinks, she smokes, she walks the streets, she makes some money, she turns herself over to the first pimp she meets, she gives up control of her life. There is one scene where she dances to a jukebox and laughs, and we can glimpse the young girl that may be inside, that may be her soul. The rest is all outside.

Godard said he shot the film in sequence. “All I had to do was put the shots end to end. What the crew saw at the rushes is more or less what the public sees.” He tried to use first takes. “If retakes were necessary, it was no good.” So Coutard’s camera was seeing for the first time, and that is why it is so involved and curious. And we see as it sees and as Nana lives, without rehearsal, the first time through. The effect of the film is astonishing. It is clear, astringent, unsentimental, abrupt. Then it is over. It was her life to live.