“Hope Floats” begins with a talk show where a woman learns that her husband and her best friend are having an affair. Devastated, she flees from Chicago with her young daughter and moves back in with her mother in Smithville, Texas. Everybody in Smithville (and the world) witnessed her public humiliation. “Why did you go on that show in the first place?” her mother asks. “Because I wanted a free makeover,” she says. “Well, you got one.” The victim’s name is Birdee Pruitt (Sandra Bullock), and she was the three-time Queen of Corn in Smithville. But she doesn’t type and she doesn’t compute, and her bitchy former classmate, who runs the local employment agency, tells her, “I don’t see a listing here for prom queen.” Birdee finally gets a job in a photo developing lab, where the owner asks her to make extra prints of any “interesting” snapshots.

This material could obviously lead in a lot of different directions. It seems most promising as comedy or satire, but no: “Hope Floats” is a turgid melodrama with the emotional range of a sympathy card.

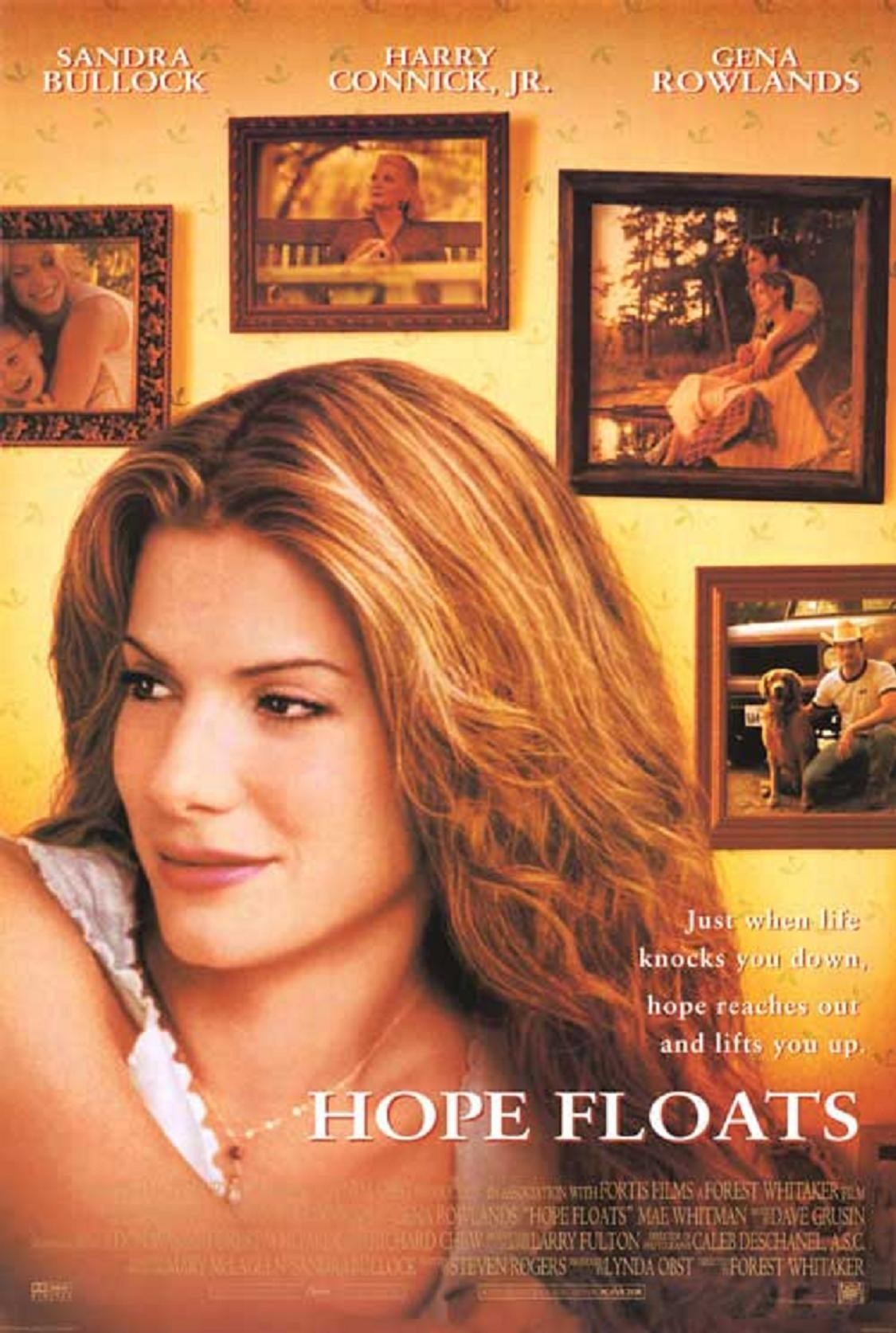

Consider the cast of characters in Smithville. Birdee is played by Bullock as bewildered by her husband’s betrayal (even though he’s such a pig that she must have had hints over the years). Birdee’s mother, Ramona (Gena Rowlands), is a salt-of-the-earth type who’s able to live in a rambling Victorian mansion and keep her husband in a luxurious retirement home, despite having no apparent income. Birdee’s daughter Bernice (Mae Whitman) is a little drip who keeps whining that she wants to live with daddy, despite overwhelming evidence that daddy is a cretin. And then there’s Justin (Harry Connick Jr.), the old boyfriend Birdee left behind, who’s still in love with her and spends his free time restoring big old homes. (There is no more reliable indicator of a male character’s domestic intentions than when he invites the woman of his dreams to touch his newly installed pine.) “Hope Floats” is one of those screenplays where everything that will happen is instantly obvious, and yet the characters are forced to occupy a state of oblivion, acting as if it’s all a mystery to them. It is obvious that Birdee’s first husband is a worthless creep. And that Justin and Birdee will fall in love once again. And that Bernice will not go home to live with daddy and his new girlfriend. And that the creeps who are still jealous of the onetime Corn Queen will get their comeuppance. The only real mystery in the movie is how Birdee keeps her job at Snappy Snaps despite apparently ruining every roll of film she attempts to process (the only photo she successfully develops during the entire movie is apparently done by magic realism).

I grow restless when I sense a screenplay following a schedule so faithfully it’s like a train conductor with a stopwatch. Consider, for example, the evening of tender romance and passion between Birdee and Justin. What comes next? A fight, of course. There’s a grim dinner scene at which everyone stares unhappily at their plates, no doubt thinking they would be having a wonderful time–if only the screenwriter hadn’t required an obligatory emotional slump between the false dawn and the real dawn.

I watch these formulas unfold, and I reflect that the gurus who teach those Hollywood screenwriting classes have a lot to answer for. They claim their formulas are based on analysis of successful movies. But since so many movies have been written according to their formulas, there’s a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy going on here. Isn’t it at least theoretically possible that after a man and a woman spend an evening in glorious romantic bliss, they could still be glowing the next day? “Hope Floats” was written by Steven Rogers and directed by Forest Whitaker (“Waiting to Exhale”). It shows evidence of still containing shreds of earlier drafts. At one point, for example, Birdee accuses her mother of embarrassing her as a child with her “road kill hat and freshly skinned purse.” Well, it’s a good line, and it suggests that Gena Rowlands will be developed as one of the ditzy eccentrics she plays so well, but actually she’s pretty sensible in this movie and the line doesn’t seem to apply.

There’s also the problem that the sweet romantic stuff coexists uneasily with harsher scenes, as when little Bernice discovers her daddy doesn’t want her to move back in with him. The whole TV talk show setup, indeed, deals the movie a blow from which it never recovers: No film that starts so weirdly should develop so conventionally. Sandra Bullock seems to sense that in her performance; her character wanders through the whole movie like a person who senses that no matter what Harry Connick thinks, she will always be known as the Corn Queen who got dumped on TV.