Few modern artists or activists have raised their middle finger with as much brazen audacity as Ai Weiwei. Twenty-two years ago, the visionary Chinese muckraker began a photography series entitled “Study of Perspective,” featuring such iconic locations as Tiananmen Square, the Reichstag, the Colosseum and the White House. Placed in the foreground of each photograph is Ai Weiwei’s hand flipping off these symbols of power, rebelling against the authority of any government intent on depriving its citizens of their freedom.

His latest addition to the series was shot this year, in which he’s seen flipping off the Trump Tower in New York City, a fitting target considering how citizens have been photographing their own single finger-salutes to the current U.S. president’s buildings well before his inauguration. Though Donald Trump is never mentioned by name in all 140 minutes of Ai Weiwei’s new documentary, “Human Flow,” the picture is, quite simply, the most monumental cinematic middle finger aimed at his scandal-laden administration to date. In its galvanizing account of the global refugee crisis, this film is a scalding rebuke to Trump’s desired wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, his abandonment of immigrants protected under the now-defunct Dreamers program and his willful ignorance of climate change.

As globalization continues to expand the interdependence of national economies, our world is shrinking at roughly the same rate as the polar ice caps. The film’s titular motif of humanity fleeing from war-torn countries mirrors the rising levels of ocean water threatening to submerge large portions of our continents, not to mention entire islands. The walls that countries have erected to block the flow of refugees is not all that different from the levees designed to halt flood waters, and as was recently demonstrated in Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, the levees can only withstand so much. What makes this film so urgent and unsettling is the indisputable proof it presents to affirm that the number of displaced people on our planet will be growing exponentially with every passing year.

Natural disasters intensified by global warming, such as those that ravaged parts of our country in recent months, are only one of the destabilizing forces demolishing every home in its path. Though Ai Weiwei cites multiple causes for the crisis, including the Arab-Israeli wars that led Palestinians to become the world’s largest refugee population, much of the blame is placed on the 2003 invasion of Iraq headed by the United States. It uprooted million of Iraqis and fueled the rise of ISIS, which has radicalized the opposition in the Syrian Civil War, while obliterating communities that don’t fit within their vision of Islam, as illustrated by another of the year’s great documentaries, Angelos Rallis’ “Shingal, Where Are You?” Not since WWII have so many people fled to Europe, bringing the total number of displaced people to well over 65 million.

Ai Weiwei certainly knows a thing or two about the agony endured by refugees. After his father, the lauded poet Ai Qing, was branded as an enemy by the Chinese government, he and his family were exiled to a labor camp in the Gobi Desert. Much like his artistic disciple, “Hooligan Sparrow” director Nanfu Wang, Ai Weiwei never conceals his presence from the audience in “Human Flow,” shooting on a handheld camera that distinguishes his footage from those captured by his team of 11 cinematographers, including the great Christopher Doyle. Whenever he appears onscreen, he is seen absorbing his surroundings while occasionally conducting interviews, making small talk with his subjects, and at one point, comforting a woman overcome with despair.

Aside from a couple Michael Moore-esque flourishes, such as when the filmmaker is confronted by suspicious cop near the Mexican border, Ai Weiwei never makes his own story part of the narrative. His goal of placing a human face on such a sprawling crisis is a daunting one that few filmmakers have been able to achieve with lasting resonance. One of the best examples was Martin Stirling’s U.K. advertisement for the Save The Children fund, which brilliantly envisioned what the Syrian crisis would look like from the perspective of a young British girl. Yet rather than juxtapose the stories of a few key refugees from around the globe, Ai Weiwei hops freely from one continent to the next, surveying as many micro-vignettes as possible while supplying statistics that often scroll along the bottom of the screen in the style of a news ticker. He also offers various quotes, many from poets, that comment indirectly on the footage, though the most pointed comes from President Kennedy, who stated that “every American who ever lived, with the exception of one group, was either an immigrant himself or a descendent of immigrants.” Migration is portrayed here not as a fanciful desire but a human right.

It’s not long before all the diverse cultures start to blur together, as the endless stream of exiles find their fate to be as uncertain as that of Godot. Stripped of international rights, many of these refugees clearly are self-sufficient people forced out of their country by war and famine. We hear a tearful interaction between displaced brothers, their faces shrouded in shadow. We see a shattered man recount the drowning of two family members, who have subsequently materialized in his dreams. We feel the rage of protestors lambasting a deal in which Turkey agreed to take back refugees in exchange for money from the European Union. Though the film has no shortage of talking heads, the majority of scenes work on the senses like pure visual poetry. Nearly every shot could be framed on the wall of Ai Weiwei’s latest exhibition, while various objects—such as a mountain of discarded life jackets—could be placed on the museum floor.

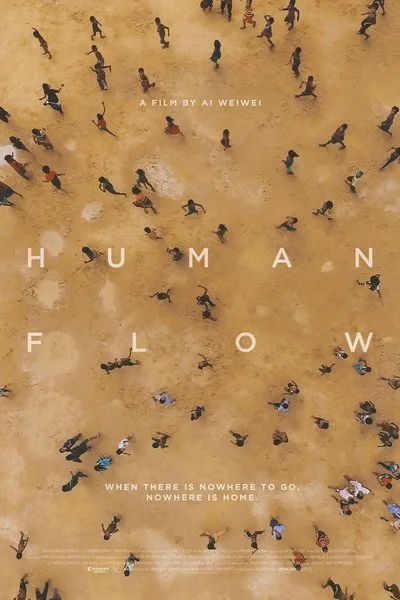

When I interviewed Werner Herzog in Toronto last year, he noted that many of the most breathtaking shots in his volcano documentary, “Into the Inferno,” could only have been captured with a drone. The new technology appears to have had a similarly liberating effect on Ai Weiwei, enabling his camera to hurtle straight toward the ground from a dizzying height at a refugee camp, which resembles a dehumanizing grid when glanced at from the air. There are echoes here of the sequence in Theo Anthony’s masterful documentary, “Rat Film,” that details how certain sections of Baltimore were systematically designed like a rat maze, keeping its impoverished citizens in their place. A particularly unforgettable scene is set in a large German building where refugees live in what appears to be a soundstage, comprised of tiny rooms with thin walls, no ceilings and no privacy. Even worse are the tents inhabited by refugees on the side of the road, mere inches away from certain death.

“Human Flow” is a towering achievement from one of the world’s foremost champions of human rights. Its subject matter may be overwhelmingly bleak, but its call for unity is profoundly invigorating. Amidst the evil hovering above us like the dark clouds in Iraq, spawned from oil wells set aflame by ISIS, genuine hope can be found in the realization that terrorists are a slim minority in the human family. Consider the shot of refugees forming a human bridge against the current of a river while traveling across northern Greece. Only when we learn to coexist do we have any hope for surviving as a species. Now that the refugee lifestyle is no longer a temporary phase but a permanent state of being, entire generations are being born without vaccinations, without education and without any sense that their lives are valued. In light of such staggering poverty, a society built on the hoarding of wealth is not only inhumane but inherently unsustainable.

As the world becomes more enlightened and connected, fanaticism increases to counter the progress, building walls that render the life existing on the other side an abstraction ripe for hateful propaganda. Terrorists thrive when their victims embrace xenophobia. With this extraordinary picture, Ai Weiwei is encouraging us to unite against the shared enemy of ignorance, while flipping it the bird in the process.