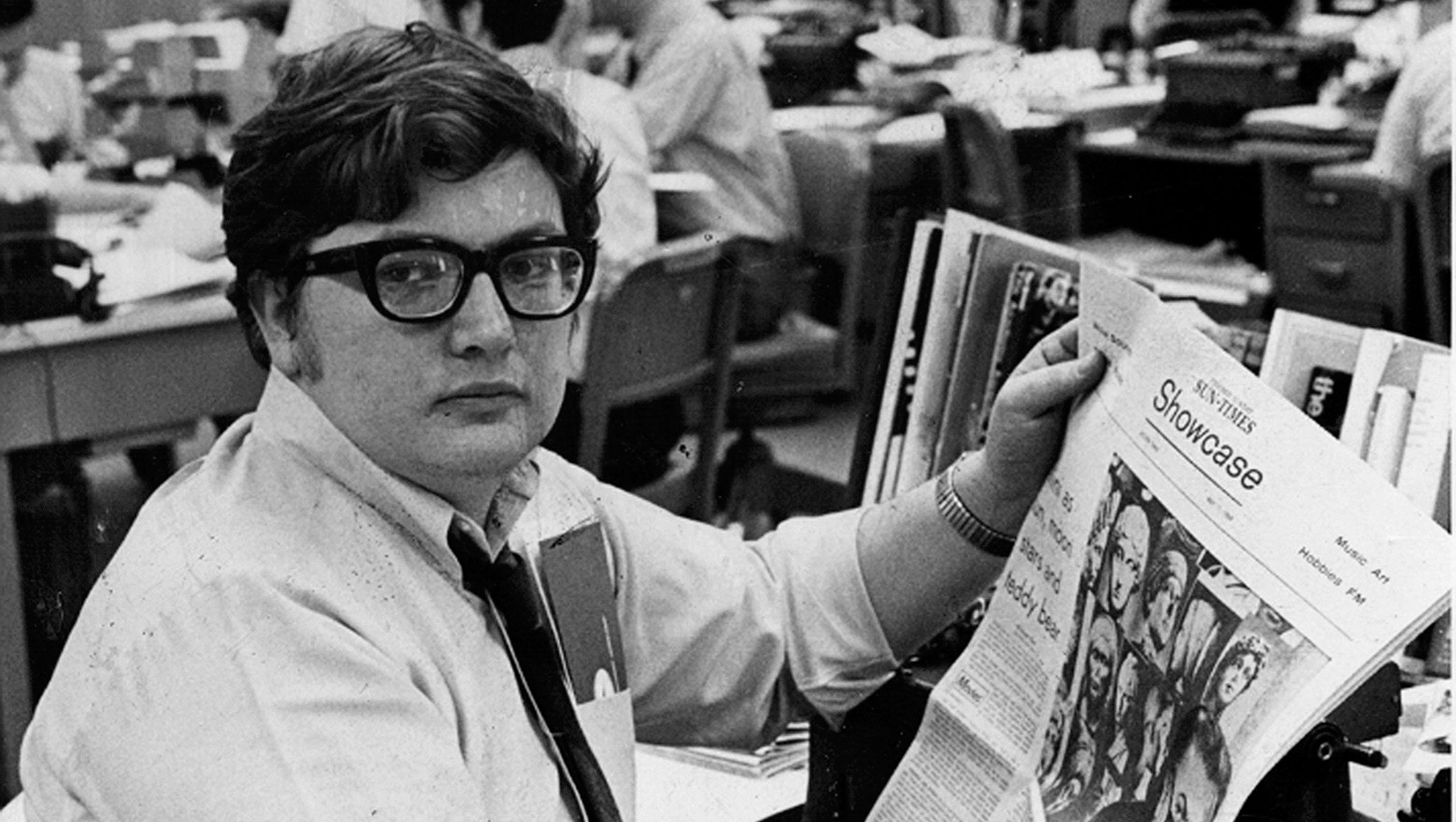

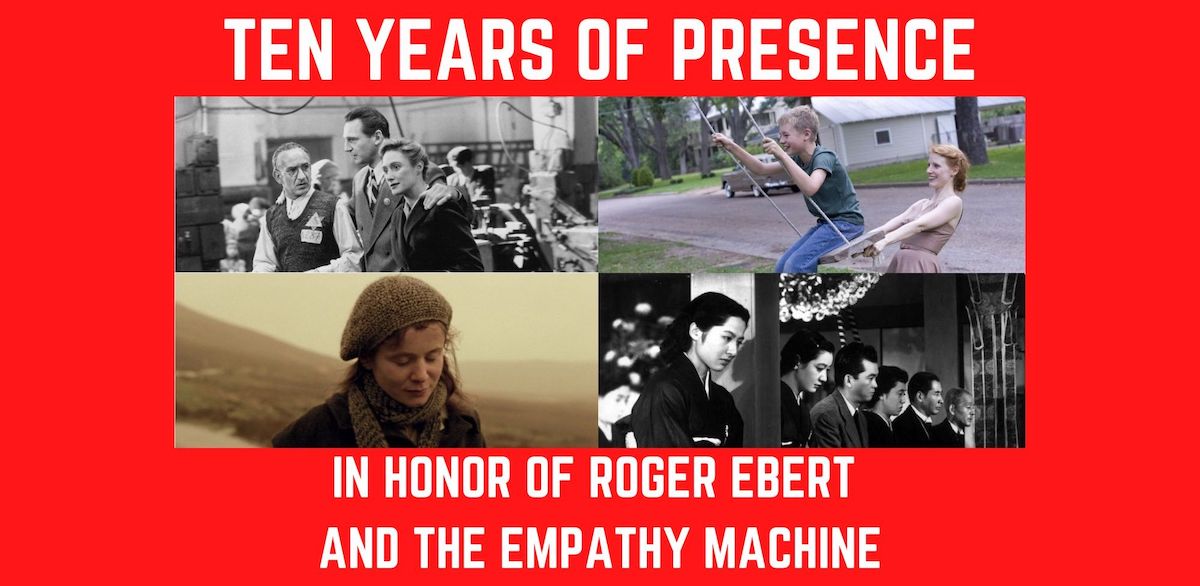

Every year, on April 4th, the day that Roger Ebert died in 2013, we give the site back to the man who made it. This year, in honor of the incredible time in which the world finds itself, we thought we’d focus on times that Roger wrote about connection and rebirth—two things that we are all in desperate need of in April 2021. There are certain filmmakers who seem to be regularly interrogating how we connect with one another, and we chose some of Roger’s favorites by those directors, including Werner Herzog, Robert Altman, and Terrence Malick. Connection can be a hard thing to define—it can be between strangers, between family members, or between a greater view of the world. We thought all 13 of the reviews on the front page today captured something about where we are in 2021, even if they were written so long ago. That’s what we try to remember on this day: Roger Ebert’s writing was as timeless as the art that he covered.

The reviews with quotes by Roger:

“What thrums beneath “Almost Famous” is Cameron Crowe’s gratitude. His William Miller is not an alienated bore, but a kid who had the good fortune to have a wonderful mother and great sister, to meet the right rock star in Russell (there would have been wrong ones), and to have the kind of love for Penny Lane that will arm him for the future and give him a deeper understanding of the mysteries of women. Looking at William–earnestly grasping his tape recorder, trying to get an interview, desperately going to Bangs for advice, terrified as Ben Fong-Torres rails about deadlines, crushed when it looks as if his story will be rejected–we know we’re looking at a kid who has the right stuff and will go far. Someday he might even direct a movie like “Almost Famous.””

“Babel”

“Yes, but there is so much more to “Babel” than the through-line of the plot. The movie is not, as we might expect, about how each culture wreaks hatred and violence on another, but about how each culture tries to behave well, and is handicapped by misperceptions. “Babel” could have been a routine recital of man’s inhumanity to man, but Inarritu, the writer-director, has something deeper and kinder to say: When we are strangers in a strange land, we can bring trouble upon ourselves and our hosts. Before our latest Mars probe blasted off, it was scrubbed to avoid carrying Earth microbes to the other planet. All of the characters in this film are carriers of cultural microbes.”

“Both of these stories, about disconnections, loneliness and being alone in the vast city, are photographed in the style of a music video, crossed with a little Godard (signs, slogans, pop music) and some Cassavetes (improvised dialogue and situations). What happens to the character is not really the point; the movie is about their journeys, not their destinations. There is the possibility that they have all been driven to desperation, if not the edge of madness, by the artificial lives they lead, in which all authentic experience seems at one remove.”

“Cleo from 5 to 7”

“There is something psychologically accurate about this. When you fear your death is near, you become aware of other people in a new way. Yes, you think of the others, you think your life is going on its merry way, but think of me–I have to die. Cléo’s awareness of that deepens a film that is otherwise about mostly trivial events.”

“I was never, ever bored by “Cloud Atlas.” On my second viewing, I gave up any attempt to work out the logical connections between the segments, stories and characters. What was important was that I set my mind free to play. Clouds do not really look like camels or sailing ships or castles in the sky. They are simply a natural process at work. So too, perhaps, are our lives. Because we have minds and clouds do not, we desire freedom. That is the shape the characters in “Cloud Atlas” take, and how they attempt to direct our thoughts. Any concrete, factual attempt to nail the film down to cold fact, to tell you what it “means,” is as pointless as trying to build a clockwork orange.”

“Encounters at the End of the World”

“Herzog’s method makes the movie seem like it is happening by chance, although chance has nothing to do with it. He narrates as if we’re watching movies of his last vacation — informal, conversational, engaging. He talks about people he met, sights he saw, thoughts he had. And then a larger picture grows inexorably into view. McMurdo is perched on the frontier of the coming suicide of the planet. Mankind has grown too fast, spent too freely, consumed too much, and the ice cap is melting, and we shall all perish. Herzog doesn’t use such language, of course; he is too subtle and visionary. He is nudged toward his conclusions by what he sees. In a sense, his film journeys through time as well as space, and we see what little we may end up leaving behind us. Nor is he depressed by this prospect, but only philosophical. We came, we saw, we conquered, and we left behind a frozen fish.”

“Le Havre”

“This movie is as lovable as a silent comedy, which it could have been. It takes place in a world that seems cruel and heartless, but look at the lengths Marcel goes to find Idrissa’s father in a refugee camp and raise money to send the boy to join his mother in England. “Le Havre” has won many festivals, including Chicago 2011, comes from a Finnish auteur, yet let me suggest that smart children would especially like it. There is nothing cynical or cheap about it, it tells a good story with clear eyes and a level gaze, and it just plain makes you feel good.”

“Robert Altman’s life work has refused to contain itself within the edges of the screen. His famous overlapping dialogue, for which he invented a new sound recording system, is an attempt to deny that only one character talks at a time. His characters have neighbors, friends, secret alliances. They connect in unexpected ways. Their stories are not contained by conventional plots.”

“Persona”

“Inside, later, Alma delivers a long monologue about Elizabeth’s child. The child is born deformed, and Elizabeth left it with relatives so she can return to the theater. The story is unbearably painful. It is told with the camera on Elizabeth. Then it is told again, word for word, with the camera on Alma. I believe this is not simply Bergman trying it both ways, as has been suggested, but literally both women telling the same story–through Alma when it is Elizabeth’s turn, since Elizabeth does not speak. It shows their beings are in union.”

“Jean Renoir’s “The River” (1951) begins with a circle being drawn in rice paste on the floor of a courtyard, and the circular patterns continue. In an opening scene, the children of a British family in India peer through porch railings at a newcomer arriving next door. At the end, the same children, less one, peer through the same railing at a departure. The porch overlooks a river, “which has its own life,” and as the river flows and the seasons wheel in their appointed order, the Hindu festivals punctuate the year and all flows from life to death to rebirth, as it must.”

“Samsara”

“I fear I haven’t communicated what an uplifting experience the film is. In its grand sweep, the chickens play a tiny role. If you see it as a trance movie, a meditation, a head trip or whatever, it may cause you to become more thankful for what we have here. It is a rather noble film.”

“The film’s portrait of everyday life, inspired by Malick’s memories of his hometown of Waco, Texas, is bounded by two immensities, one of space and time, and the other of spirituality. “The Tree of Life” has awe-inspiring visuals suggesting the birth and expansion of the universe, the appearance of life on a microscopic level and the evolution of species. This process leads to the present moment, and to all of us. We were created in the Big Bang and over untold millions of years, molecules formed themselves into, well, you and me.”

“The key performance is by Maribel Verdu as Luisa. She is the engine that drives every scene she’s in, as she teases, quizzes, analyzes and lectures the boys, as if impatient with the task of turning them into beings fit to associate with an adult woman. In a sense she fills the standard role of the sexy older woman, so familiar from countless Hollywood comedies, but her character is so much more than that–wiser, sexier, more complex, happier, sadder. It is true, as some critics have observed, that “Y Tu Mama” is one of those movies where “after that summer, nothing would ever be the same again.” Yes, but it redefines “nothing.””