The films of the prolific South Korean writer-director Hong Sang Soo are for the most part set in the contemporary world, but they rarely depict the bustle of our times. His characters interact in settings that are quiet, sometimes practically deserted. When a character ventures out into a location of potential action and disorder—in this movie, that character is a cat—we only see it upon its (spoiler alert, I suppose) return to where it took off from. While the ideas and concerns of its characters are those of urbanites, they’re articulated in settings suited for reflection.

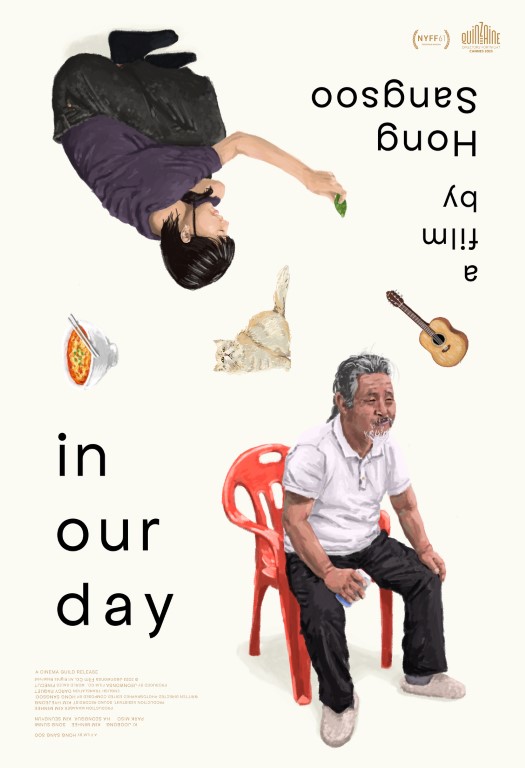

Hong’s new film, “In Our Day,” is not atypical—it’s a plain-looking, often wry, and lightly nourishing character study with a diptych structure that adds enigmatic intrigue to the proceedings. Its scenes are introduced with texts of an almost remarkable banality. The first one, for instance, reads: “Sang-won relies on her friend Jung-soo after moving back to Korea…but she thinks the only one she can truly rely on is herself.” Sang-won is played by Hong regular Kim Min-hee, who, in addition to returning from time abroad, is processing a sundered relationship. She and Jung-soo (Song Sun-mi) don’t get up too much in their first scene together. They do some appropriate worship of Jung-soo’s cat, named Us (as in “This is Us,” which I reckon isn’t a reference to the U.S. nighttime soap), discuss their habits (nothing wrong with “a little wine while working,” Jung-soo observes) and steer around the question Jung-soo aims at her friend: “But why do you want to be an actor?”

The parallel story, such as it is, focuses on the old, or old-ish, poet Hong Ui-ju (Ki Joo-bong), newly renowned among the youth in South Korea, here being filmed by a young documentarian and visited by a young actor. On a day when he’s feeling self-conscious about a doctor’s orders to stop drinking and smoking, the poet is mildly flummoxed by the offerings of the male fan: some smokes and a bottle of high-end booze. Because this is a Hong Sang-soo picture, we know these will be consumed, and they are here without too terribly dire consequences (which is not always the case in this auteur’s filmography). As the poet’s visitor declares, “You’re really famous for loving alcohol and cigarettes.”

Hong’s early films were about young adults quietly screwing up their professional and personal lives, so why an old poet in this picture? Well, Hong himself is getting up there in years, a graying eminence in cinema. Kim Min-hee, about two decades Hong’s junior, took a hit in her mainstream career when she became personally involved with Hong. If you know this, it makes the seemingly unrelated musings of the actress and the poet more particularly resonant. But if you don’t, they’re reasonably resonant anyway, and the things that constitute the small dovetails connecting the two narratives—acoustic guitars, chili paste—remind us of the potentially marvelous in the everyday.