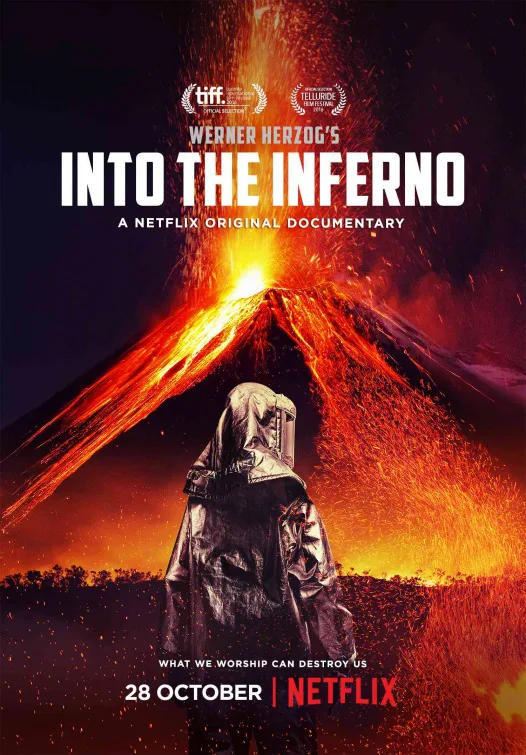

The documentary “Into the Inferno” sums itself up in its opening moments. A gliding helicopter shot takes us across the Vanatu Archipelago in the Galapagos, over waves of ground that resemble dried black pudding, until we see a group of tiny figures on the crest of a mountain. The camera draws close to them, eventually peering over their shoulders to reveal what they’re looking at: a gigantic pool of magma. Then comes a succession of long shots of the magma. The film is hypnotized by it.

So are all of the people profiled in this movie, which is directed by Werner Herzog but credited as “A film by Werner Herzog and Clive Oppenheimer.” Oppenheimer is a Cambridge volcano expert, or volcanologist, a slim man with a kind face and voice. He serves as the on-camera guide for Herzog, interviewing fellow volcanologists as well as people who spend most of their lives living or working near active volcanoes, including a woman who works at a monitoring station and a group of archeologists digging up shards of bone preserved by cooled and hardened lava. (“Every single piece of bone is a keeper,” Herzog intones over footage of a dig site, one of many bits of voice-over that sounds a lot funnier when he says it.)

Volcanoes are an ideal Herzog subject. His great theme is obsession. His filmography is filled with people who are obsessed with achieving a goal, learning all they can about a subject, or getting to the heart of a mystery. Not only do they seem not to care whether their obsession destroys them, obsession might be the fuel of their existence. At one point Herzog detours to show us documentary footage of Katia and Maurice Krafft, a married team of volcanologists. The sequence ends by telling us that they were killed by a fiery avalanche. This piece of information is conveyed with an undertone of respect, as well it should be. They died doing what they loved, which in Herzog’s eyes amounts to a hero’s death.

The many lengthy shots of erupting volcanoes, rivers of lava and pools of magma soon start to feel like obvious metaphors, not just for the single-mindedness of people whose lives revolve around volcanoes, but for Herzog’s obsession with those same people, as well as for his obsessive personality generally, which seem unbearably self-regarding if he weren’t such a witty, self-deprecating storyteller and guide. But these same shots are beautiful on their own terms, as spectacle. A big part of the appeal of films, fiction and nonfiction alike, is the chance to gawk at amazing things, in particular amazing things that might destroy us were we to encounter them in real life. Few natural phenomena are simultaneously as beautiful and terrifying—and therefore as inherently cinematic—as volcanic activity. Most people will see “Into the Inferno” as I did, on a small screen; I envy those who will see it on a movie screen, especially a big one, because this is a film where scale makes a difference. Cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger’s camera always seems to be in just the right place, whether he’s capturing volcanoes themselves or people talking about volcanoes while lava spews in the background behind them.

Early in the film, Mael Moses, chief of a tribe that lives in a village at the base of the volcano we saw in that opening sequence, tells Oppenheimer that their religion revolves around “how powerful that fire is,” and says “the fire expresses the anger of the gods who live in the volcano.” The next group of people we meet in the film are, per Herzog’s narration, “a strange and wonderful tribe of volcanologists, some of them overcome by altitude sickness”; the first shots of the scientists show them splayed out in a camp near the lip of the volcano, resting. Like the people of the village, this “tribe” respects the power of the volcano but isn’t scared of it. One of them says that sometimes lava balls are flung high into the air by the magma pool, but that it’s possible to evade them by eyeballing their arc into the sky, judging where they’ll land, and stepping a little bit this way or that way. “Keep your attention toward the lava,” one says, “look up, and move away.”

This is a key movie in Herzog’s late phase as a filmmaker. In the back half of his life, he has become a celebrity and impresario as well as a director, the subject of memes and parody Twitter accounts, and a person employed as an actor or personality in the films of other directors who are fascinated by Herzog. There are quite a few purists who think this phase is a step down for him—they miss the forbidding and mysterious wild man who made such classics as “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” “Fitzcarraldo” and “Little Dieter Needs to Fly,” and they seem to resent not just the fact that the rest of the world now knows about Herzog, but that all the adulation has made him cuddly, and his films warmer, more accessible, and perhaps in some ways more superficial.

It’s true that Herzog documentaries now are not exclusively about the subject but Herzog learning about the subject, and being Herzog, and reading narration that increasingly seems aware of itself as the sort of narration that Werner Herzog would read. (My favorite line in this new movie, spoken over images of the archeological dig site, is, “Why this particular spot, and not back there where the goats are roaming?”) There are conversations in the film between Oppenheimer and Herzog that aren’t germane to the story; they feel like celebrations of Herzog’s Herzog-ness, especially when Oppenheimer talks about the perception that Herzog is insane and assures him, “You seem quite sane to me.” Herzog does seem quite sane, in this film and others, and I don’t mind that he’s increasingly become a generalist, using his fame to visit exotic places and ponder subjects he knows considerably less well than the experts he interviews onscreen.

Two factors prevent Herzog’s documentaries from becoming purely narcissistic. One is the fact that he’s always been as much of a self-portrait artist as a portrait artist, treating the universe and all of history as his mirror, then projecting himself onto his audience. The other factor is the humble attitude his films adopt toward people who live in unusual or dangerous circumstances, and whose obsessiveness seems driven by curiosity and love. Every single person interviewed in this film is in some way a mirror of Herzog, which means that even though they are real people, they become Herzog characters. If you look at the structure of this film, or almost any of Herzog’s recent films, you’ll see that they’re broken into discrete sections of five to ten minutes apiece, each focusing on obsessive individuals or “tribes.” If you go into a Herzog documentary hoping for a definitive, deep look at a certain subject, you’re bound to come away disappointed. But if you go into them expecting a series of portraits of obsessed people, each painted by one of the most likable obsessives in cinema, you’re likely to come away satisfied.