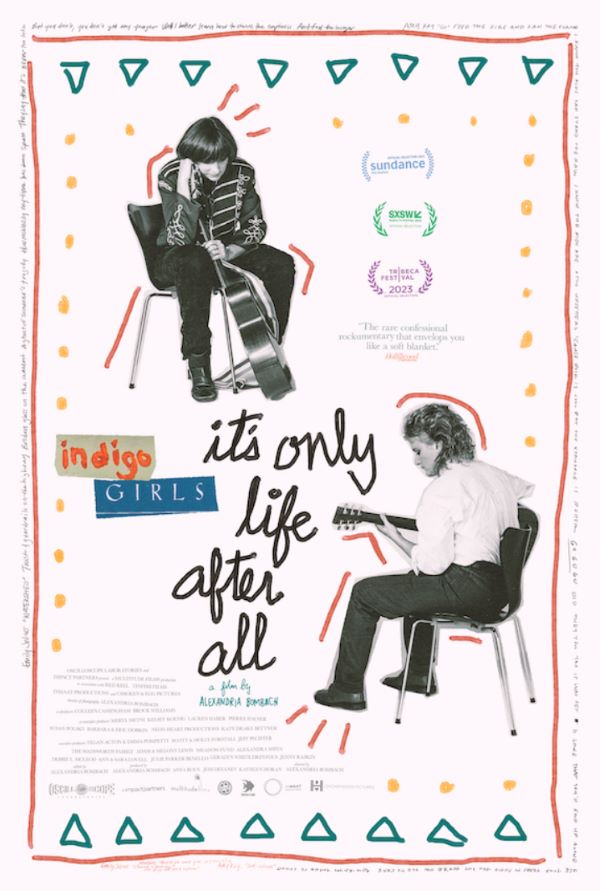

There’s a lot of ground to cover in “It’s Only Life After All,” a documentary about the Indigo Girls. The duo (Amy Ray and Emily Saliers) have been performing together, after all, for 40 years. The phenomenon of the Indigo Girls is well worth exploring, but director Alexandria Bombach gets bogged down in the weeds, relying so heavily on Ray’s personal collection of archival footage that she misses the opportunity to dig into the deeper meaning of their career, cultural context and impact. There are interviews with audience members who often speak through tears about how the Indigo Girls saved their lives. Such sentiments are often mocked, but they shouldn’t be. Indigo Girls songs mainline into the lives of their audience members, expressing the inexpressible. If you already are a fan of the Indigo Girls (and this writer is), then you know what their music means and the impact it’s had on you. But if you don’t know, if you want to learn more, “It’s Only Life After All” doesn’t get the job done, even at 2 hours long.

Ray and Saliers met in grade school, and Amy was drawn to the guitar-playing Emily, who was a year older. They started making cassette recordings together; singing, harmonizing, and writing songs. The chemistry was immediate. There was a gap when they went to different colleges, but both ended up at Emory University, picking up where they left off. Atlanta was their stomping ground. They had no manager, but they had drive, as well as a passionate local fan base. It was the mid-’80s. They were different from what else was out there: close harmonies, two acoustic guitars, poetic lyrics, a distinct sound. Amy’s voice is rough and guttural. Emily’s voice is clear and high, with a wistful quality. The blend of these opposite essences is the Indigo Girls sound.

In 1989 came “Closer to Fine,” their breakout hit. I still remember where I was when I heard it for the first time (on the radio at the grocery store in Beacon Hill where I was a cashier). The harmonies stopped me in my tracks and the lyrics were so unusual they forced you to listen. Michael Stipe brought them on tour with R.E.M. Mainstream success was disorienting, with unusual stresses and tensions. Ray and Saliers are lesbians, and they had discussions about coming out publicly. When they finally did, a reporter framed it as “This is the year you’ve come out.” Amy interrupted, “I’ve been out.” The homophobic atmosphere of the 1980s can’t be overstated, with AIDS still decimating a generation, and almost no public figures declaring themselves. There were other artists dealing with similar things, either directly before the Indigo Girls or directly after, none of whom get name-checked in “It’s Only Life After All”.

There’s a claustrophobia in the documentary’s approach, even a laziness. Ray and Saliers are the sole interview subjects. The “talking head” format is a tired cliche, but “It’s Only Life After All” would have benefited from more voices, industry voices, cultural voices, who could “place” the Indigo Girls in a wider context. What was going on around them? What part of the folk tradition did they fit into (or not)? At one point, Amy jokes, “Is there a category for Lesbian Christian Folk?” There is clear Christian imagery in many of their songs, and yet this intriguing comment is never followed up on. Why? There’s a moment where Amy talks about the “folk scene” in the mid-’80s, and how it was mostly “quiet,” “intellectual,”, “serious,” whereas they were loud and raucous. To illustrate this point, Bombach inexplicably inserts a clip of Judy Collins in what looks like the late-’60s, sitting on a stool playing guitar, hair down her back. This is to show what the Indigo Girls didn’t want to be, presumably. Judy Collins’ heyday was 20 years before the Indigo Girls came along. Neither Ray nor Saliers mention “Judy Collins” as an artist they didn’t want to emulate. Don’t dis a folk legend to make your point.

The Indigo Girls were not exactly embraced critically. They were never profiled in the big music mags, and they were called “earnest” and/or “humorless”. I guess critics somehow missed lines like “Every five years or so I look back on my life and have a good laugh”. I think this verse in their first hit is pretty funny:

And I went to see the doctor of philosophy

With a poster of Rasputin and a beard down to his knee

He never did marry or see a B-grade movie

He graded my performance, he said he could see through me

I spent four years prostrate to the higher mind

Got my paper and I was free

There are plenty of humorless earnest male musicians who don’t get treated with the dismissive attitude the Indigo Girls faced. Then there was what should be a national embarrassment: The Indigo Girls were nominated for a Best New Artist Grammy and lost to the now-disgraced Milli Vanilli. They did eventually win a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Recording, but the stain remains. Despite the lack of establishment support, the Indigo Girls survived the first wave of fame, and have been playing packed shows for decades.

“It’s Only Life After All” includes interesting sections on the nuts-and-bolts of their songwriting process. Amy admits Emily is the more gifted songwriter. There’s fascinating footage of Amy trying, repeatedly, to work out the harmonies for the bleak “Girl with the Weight of the World in Her Hands”. It shows the effort behind those seemingly effortless harmonies. Less interesting are the sections on the Indigo Girls’ activism. Despite the time devoted to it, it’s surface-level only. The Honor the Earth tours, in particular, a collaboration led by activist Winona LaDuke, deserve a deeper dive. Both Ray and Saliers speak of not wanting to “talk over” the voices of marginalized people, and yet the documentary only provides commentary from them.

The recent jukebox musical “Glitter & Doom” shows how far the Indigo Girls’ songs have traveled. Their music is timeless. This is a very significant shared career and “It’s Only Life After All” struggles to express why. It assumes you already know.