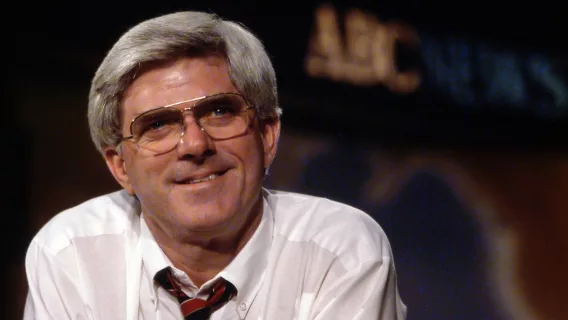

It takes a lot of courage to play a buffoon, and Dabney Coleman, who passed on May 16 at the age of 92, had it in spades. Not many character actors of his constitution in 1980 — white, male, middle-aged, thick mustache parting only to deliver his baleful bass of a voice — would have dared make a fool of themselves as the “sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical bigot” boss Franklin Hart Jr., who’d push around his three female subordinates (played by Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton) only to find himself at their comic mercy in the now iconic girl-power workplace comedy “9 to 5.”

But it also took an actor like Coleman to pull such a role off: A veteran of both TV comedy and filmic drama, he, like another contemporary of his, Leslie Nielsen, knew how to leverage his stiff, all-American businessman looks and stentorian charm for peak deadpan comedy. He looked like a jerk and acted like a jerk. But because Coleman wasn’t a jerk, he knew exactly how to use those powers for good. And that he did, leaving behind a six-decade resume filled with comic oafs, boorish bosses, and good/bad dads and their fictional video game counterparts.

Born in Austin in 1932, Coleman grew up in Corpus Christi before studying at the University of Texas at Austin. His journey to acting was a bit circuitous; he fell into acting after meeting film actor Zachary Scott, a friend of his first wife’s: “Believe it or not, I was smitten with becoming an actor just from that meeting,” he told Texas Monthly. While he built a steady career on Broadway and television in the intervening years, he played the usual serious fare — cops and squares, mostly. But then came Merle Jeeter, the sniveling mayor of the long-running soap opera parody “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman,” and the rest was history.

In Merle’s six-episode arc on the show, we see the same comic chops Coleman would leverage in some of his greatest roles: The deadpan seriousness, the honeyed Texas drawl, the innate swagger that comes from being able to wear a mustache like that (which he grew for the show, and smartly never seemed to shave afterwards).

But while “Mary Hartman” proved Coleman’s aptitude for playing the buffoon, it was undoubtedly “9 to 5” that catapulted him, Leslie Nielsen-like, to the upper echelons of film and TV comedy. Franklin Hart Jr. remains one of ’80s cinema’s quintessential comic villains: the pluperfect archetype of the crass, sexist boss who treats his employees like dirt and his secretaries like meat. He felt sprouted from Ronald Reagan’s rib like Eve from Adam — genetically engineered in a vat to service the venal needs of late-stage capital.

He had to be, really; after all, Fonda, Tomlin, and Parton were going to fantasize about, then act out, increasingly elaborate revenge fantasies against him, a crusade to emasculate the hypermasculine systems that stood in the way of work and wage equality. But Coleman plays him with such devilish relish, such unmitigated confidence in the supremacy of his sex and class, that watching his eyes bulge with each new indignity our heroic trio of ladies beset upon him is nothing short of delightful.

From there, he leveraged his “9 to 5” fame into not just more comedic roles (e.g. his imperious TV soap director in “Tootsie“), but dramatic ones as well. He reunited with Jane Fonda for “On Golden Pond,” this time as her sympathetic love interest; he also played a computer scientist (all business) in 1983’s “WarGames.” But crucially, I’ll always remember him from the 1984 computer game thriller “Cloak & Dagger,” where he plays both the distracted dad of Henry Thomas’s imaginative child protagonist and said child’s vision of his favorite spy character, Jack Flack. Given how often Coleman played heavies and oafs, it was nice to see him get to play the hero for once: the dashing man of action a son desires in a father figure and the disappointing but still-trying everyman he often gets.

While his star waned in the 1990s, it did so only by degrees; like so many character actors before and since, Coleman simply took a couple of paces back and worked steadily in film and television for the ensuing decades. He had some strong roles, too, not just as jerks. Sure, he played villains and heels in “Boardwalk Empire” and “Buffalo Bill,” but one of his final roles was a one-episode appearance as Kevin Costner’s dad on “Yellowstone” — finally playing the kind of cowboy the Texan actor could have leaned on his whole career, but who blissfully got to be so much more.

The blessing and the curse of all great character actors is that, if you’re good enough at your job, your work becomes invisible. Uncelebrated. In many ways, that was Coleman: Whether before or after “9 to 5,” he was the kind of reliable presence you could slot into any number of gumshoes, executives, or government officials, and he’d nail it with little fanfare. But that was also the beauty of Coleman’s unassuming work–He made swinging from a garage door or playing a computer-game hero made manifest seem effortless. His presence was a comfort. You could be sure you were in good hands. And, dollars to donuts, you could be pretty sure he’d be a real jerk.