James Caan’s Sonny Corleone in “The Godfather” (1972) is the family hothead, a flashy stud incapable of being strategic like his father Don Corleone or his brother Michael. (We see so little of the Corleone matriarch in this movie that it’s difficult to say if Sonny gets some of his impulsive traits from her side of the family.) Caan’s Sonny is the sort of wise guy that is clearly going to get whacked sooner rather than later, but he’s also the sort of guy that gets remembered fondly, whereas his brother Michael is someone who produces nothing but fear and dread in others.

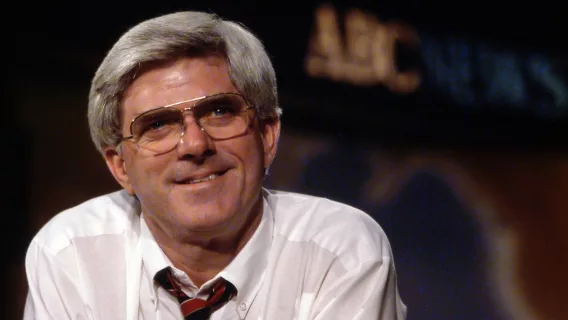

Playing Sonny in “The Godfather” got Caan an Oscar nomination and made him a star of the 1970s, an era when he was offered practically every solid male role and turned quite a few of them down. He had been born in the Bronx and grew up in Queens, the son of Jewish immigrants from Germany. Caan played football in school (he always kept his formidable physique), and then attended Hofstra University, and one of his fellow students there was Francis Ford Coppola, the director of “The Godfather.”

Caan studied acting seriously for five years with Sanford Meisner at the Neighborhood Playhouse, and this paid off, for at his best he was very in the moment, and this is what made his Sonny Corleone so vivid. “I just fell in love with acting,” he said. “Of course, all my improvs ended in violence.” He made TV appearances in the 1960s, holding a knife to the neck of future erotica director Zalman King for an episode of “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour,” and he turned down a regular TV series because he was more interested in proving himself as an actor and less interested in making a lot of money.

Caan menaced Olivia de Havilland in the exploitation picture “Lady in a Cage” (1964), where he swaggered around in ultra-tight jeans and flaunted his hairy chest while rubbing poor de Havilland’s nose in the lowest vulgarities he could think of. Like many actors of his era, it was clear that Caan was influenced by the rebellious mannerisms of Marlon Brando and James Dean, and with Caan this mimicry came spiced with his own very distinctive sexuality, which is why his Sonny Corleone sometime struts around like a peacock and girls whisper and laugh about his carnal intensity. Caan worked with Howard Hawks on “Red Line 7000” (1965) and “El Dorado” (1967) and Robert Altman on “Countdown” (1968), and he continued to show promise and a smiling confidence that could sometimes have a nasty edge to it.

Caan displayed some range when he was cast by Coppola as a former football player who was mentally handicapped on the field in the moody character study “The Rain People” (1969), which contains one of his most appealing and vulnerable performances, but he got more attention for the TV weepie “Brian’s Song” (1971) before Sonny Corleone made him a star and he went on a star trip that included lots of drug use and many visits to the Playboy mansion.

It cannot be said that Caan always chose his projects wisely during his heyday in the 1970s. He had some chemistry with Barbra Streisand in “Funny Lady” (1975), especially in a clearly improvised scene where they throw face powder on each other, but other movies saw Caan cast well outside his best levels, like “Chapter Two” (1979), where he is very unconvincing as a Neil Simon-like playwright and seems to know how miscast he is. When he directed a movie called “Hide in Plain Sight” (1980), it did not find an audience.

But there were two movies from this time where Caan was very much in his element and at the center: “The Gambler” (1974), which had a script by James Toback, and especially “Thief” (1981). In Michael Mann’s very abstract film, Caan plays a jewel thief who is asked to carry lots of scenes with just a watchful face and cautious body language, and this was all very unexpected since Caan was known for exuberance and a sexuality that was always close to boasting. His performance reveals a disquiet that Caan had never touched on before. Sonny Corleone will be what he is remembered for, surely, but “Thief” should definitely be next in line for remembrance whenever Caan is considered.

It was at this point in the early 1980s, when he was in his forties, that Caan’s career and life went to pieces. From 1982 to 1987, he did not act in movies, and when he came back in Coppola’s “Gardens of Stone,” he was clearly older and sadder, with a slightly desperate quality in his eyes. His new vulnerability seemed heightened when he played the best-selling author trapped by Kathy Bates in “Misery” (1990), a movie where the situation from “Lady in a Cage” is flipped around and it is he who gets tormented and broken, with just a flicker of that rather harsh and unnuanced hairy-chested masculinity that had been his trademark.

Caan played a smiling phony of a performer opposite Bette Midler in “For the Boys” (1991), but he could not work up the rapport with her that he had with Streisand. Caan worked steadily throughout the 1990s, trying to be comic in “Honeymoon in Vegas” (1992) and appearing in Wes Anderson’s first movie “Bottle Rocket” (1996). He returned to gangsterdom for James Gray’s “The Yards” (2000), which is clearly a film made in the Coppola mode and uses Caan as a figurehead of the Coppola style of filmmaking from the 1970s.

Caan was one of many in the cast of Lars von Trier’s “Dogville” (2003), and he finally did star in a TV series at this time, “Las Vegas.” He worked sometimes with his actor son Scott, one of five children from his four marriages, and Caan wound up his career with a series of low-budget crime films and thrillers; his last film saw him opposite Ellen Burstyn in “Queen Bees” (2021). He was vocally right-wing and pro-Trump at the end of his life, and this was as unfortunate as some of his later pictures. But Sonny Corleone in “The Godfather” is enough to make anyone a movie immortal, just as Frank in “Thief” is the performance that shows us some of what Caan worried about and felt deep down behind that cocky smile of his.