Pop star Katy Perry grew up singing in church. And in “Jazz Fest: A New Orleans Story,” a documentary celebrating the 50th anniversary of the annual New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, Perry sings “Oh Happy Day” in front of a robed gospel choir. The only reason it doesn’t raise the roof is that the festival is outdoors. Still, you can almost feel souls, possibly even your own, lifting toward heaven as Perry, dressed in a silvery leotard, segues into her hit, “Firework.”

That is one of dozens of thrilling, genuinely uplifting moments in this year’s successor to 2021’s Oscar-winner, “Summer of Soul.” It’s as spicy a combination of different ingredients as the gumbo ladled out so lusciously on screen, and edited with the syncopated rhythms of the music described by one commentor as “throw[ing] the melody out like a boomerang” and then catching it again, a vivid, evocative depiction of half a century of music, food, and community. The history and commentary are fine, but the musical numbers are sensational.

Perry’s gospel number is more than just a musical highlight. It also exemplifies the festival’s—and the film’s—foundational theme, the way that all music and all people are connected, and combining the cultures brings everything together. While the festival is proudly named for the musical genre that was born in New Orleans, it just as proudly features almost every other genre as well, including rock, blues, gospel, pop, R&B, world, hip-hop, spoken word, and soul. “Jazz welcomes all her children for a visit,” one of the participants describes the mix of performers. Syncopated rhythms and experimentation filters through all of the genres. And so, the festival has something for everyone, but, more than that, everything is for everyone. The performance spaces are laid out so that it is almost impossible to limit yourself to just one kind of music. On your way to the next performance, you cannot help being enticed by the sounds you hear along the way.

And also by the food. The only thing New Orleanians take as seriously as what they listen to is what they eat, and we can almost smell the offerings from the tents providing tens of thousands of meals a day. Some of the performers laugh as they describe the dishes, their inability to resist them, and the irreversible damage it inflicts on their bodies. “Everybody eats; everybody dances,” says Quint Davis, who was barely out of his teens when festival founder George Wein hired him to organize the festival. Davis compares that moment to being a baseball card-collecting kid invited to pitch for the Yankees in the World Series. Still with the festival today, he has the same sense of ecstatic joy that we see in adorable archival footage of a very young Davis in a musical parade.

Wein, the jazz impresario behind the Newport Jazz Festival and the Newport Folk Festival, was asked to design and produce a unique festival for New Orleans in the 1960s. There was a significant obstacle; Jim Crow laws were still in effect. Not only would they prevent the mixing of Black and white musicians, Wein’s own marriage to a Black woman was still illegal. So, they had to wait until 1970. Only about 350 people attended that first year, which featured Mahalia Jackson and Duke Ellington, setting the standard for the musical legends who would appear over the next five decades. Many of them appear on-screen to share their memories and explain what it is that makes this festival—now with so many attendees it’s temporarily the sixth largest city in the state—create such an enduring sense of community.

Some of the most insightful comments come from Suzannah Powell (stage name: Boyfriend), with her hair rolled up in the 1960s-style curlers she wears on stage. She talks about the uniquely analog experience of wandering through the performance spaces, smelling the beignets. “Whether you want to or not, you’re going to experience something that your computer would not have put in your feed.” The son of the founders of the famous Preservation Hall laughs about the “January babies” who arrive nine months after the festival, himself one of them.

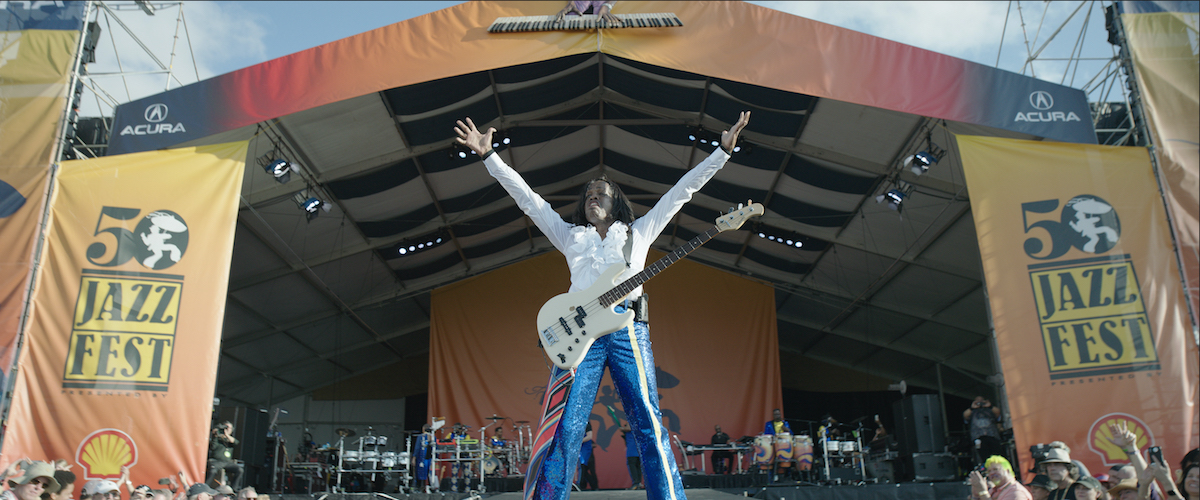

As thoughtful as the comments are and as interesting as the archival footage is, it is the performances that give the documentary its most thrilling moments, especially those we get to see in full. The film veers off to cover the impact of Katrina. The message of resilience, though, is delivered most powerfully with the music. Some of the highlights include a reunion of the Marsalis family musicians and a literally incendiary Pitbull number. Reverend Al Green is “reincarnated as himself,” singing his classic “Let’s Stay Together” in his first concert appearance after seven years as a preacher and church singer. Festival stalwart Jimmy Buffett (also a producer of the film) amends the lyrics of “Margaritaville” for the Jazz Fest audience and covers a Rolling Stones classic. Aaron Neville sings “Amazing Grace.” The festival all but bursts throughout the movie’s run-time, with so many enticing directions worthy of further exploration. I’d watch an entire film just about the band names, or one about the differences between Cajun and zydeco. After the pure joy of the musical numbers, the best thing about this movie is that even with all of its abundance it leaves you wanting more.

Now playing in select theaters.