Jean Eustache’s “The Mother and the Whore,” a 1973 French film that is now being revived in a new 4K restoration, is a work of strange, ineffable power, a power unlike that of any other film I know. One can emerge from other masterpieces dazzled, intellectually, or emotionally ravished, but this legendary cinematic landmark is apt to leave its most fervent admirers feeling something else: bewitched. Though nominally akin to various other movies, its magic is singular, unique, as are the reactions it provokes. The director Ira Sachs has said, “If I was only to be able to watch one film again for the rest of my life, it would be this one.”

I understand Sachs’ sentiment. I feel similarly. I saw the film when it was first released in the U.S. in 1974 and would catch it whenever possible, in festivals or revival houses, thereafter. (I feel strongly that it should be seen in a theater, on the big screen. I have a VHS tape of it that’s been sitting next to my TV for decades, never watched.) After I moved to New York in 1991, I saw it at the newly opened Walter Reade Theater and was so struck by the perfect match between movie and theater that I started raving to friends that New York should pass an ordinance decreeing that the film should be shown there every year. (It inspires such dizzy obsessiveness.)

“The Mother and the Whore” runs three hours and 40 minutes, and that length, I think, has much to do with its mesmerizing force. Early on, you realize you’re not in for a conventional story. Rather, Eustache has plunged you into a small world of young characters in contemporary Paris and invited you to live with them and observe the ebb and flow of their lives; doing so soon becomes hypnotic.

The three main characters—two women and a man—are connected by erotic and romantic bonds that evolve as the narrative unfolds. Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud) is a handsome young long-hair, always chicly attired in flowing scarves, who would seem to be a fledgling intellectual or artist, except that we never see him working on anything. He evidently lives off his lover Marie (Bernadette Lafont), who constantly seems torn between love for him and exasperation with his relentless philandering.

When we first see Alexandre, he borrows a car from a neighbor. He drives in pursuit of an ex, Gilberte (Isabel Weingarten), who’s about to enter a university class and is involved in another relationship. Alexandre bluntly proposes that she dump the guy and marry him. She even listens to the proposal and argues with him, bespeaking a lingering attachment. But she knows Alexandre all too well. And through long and wearying familiarity, she ruefully recognizes his mood: call it self-centered romantic desperation.

Aside from Marie’s spare apartment, with its mattress on the floor and adjacent stereo, much of the action in the film takes place in two famous Left Bank cafes, Les Deux Magots, and Café de Flore. These are Alexandre’s hangouts and happy hunting grounds and it’s in one that he espies a young woman who looks remarkably like his ex. But Veronika (Françoise Lebrun) is a different person entirely. She lives in a dorm for nurses—not the most convenient place for hookups, but she says all the girls bring men in—and she speaks very frankly about her active sex life. This not only attracts Alexandre immediately, it also sets the stage for the menage a trois that will result when he’s able to bring Veronika and Marie together.

Sex is central to all the actions and interactions we see in the film, but “The Mother and the Whore” is not an erotic film in the usual sense. The few sex scenes are too mild to even qualify as softcore. But sex isn’t the point. For all the characters, it’s a route to something else. Marie, poor thing, evidently hopes it will lead her to a stable relationship with Alexandre, which seems the unlikeliest of outcomes, to put it mildly. Alexandre not only sees it as a source of immediate gratification but also as a pathway to an ideal romantic/erotic relationship somewhere in the hypothetical future. And Veronika, the most interestingly complex of these characters, appears to value sex as an escape from the barrenness of her life, but her claims of having no greater aspirations seem to betray a nihilism that can’t quite smother such a goal.

When I first saw “The Mother and the Whore” I was in my early twenties, younger than the characters in the film. Looking back decades later, I see those characters as embodying challenges and confusions that often come at a particular time of life, one’s late twenties, before more lasting career and personal associations settle in. The film captures this period’s emotional volatility, vulnerability, and sheer messiness—which many of us can continue to identify with long after it’s over—with scrupulous accuracy and precision.

Eustache reportedly drew the film’s emotional content from his own life, and I think that is one key to its greatness: It has the gut-level passion and authenticity of a first-hand account, one by an artist who perhaps sensed that he needed to pack everything he had to say into one massive opus. Autobiography in French cinema, of course, had been kick-started by François Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows,” which led to an ongoing series of Antoine Doinel films, all starring Jean-Pierre Léaud as Truffaut’s alter ego. But those films were not only essentially comedic, they also emerged from the buoyant early ‘60s, whereas “The Mother and the Whore,” the product of an artist whose turn of mind might be called forensically confessional, was one of many films of its era brooding on the dark, deflating aftermath of May ’68.

That this edgy probe into personal and cultural depths still has an air of grace and lightness owes much to Eustache’s style. As in earlier New Wave classics—think of Godard’s “Masculine Feminine” and “Vivre sa vie”—Pierre Lhomme’s luminous black and white cinematography combines documentary-like immediacy and classical polish, qualities perhaps most important to Eustache’s subtly elegant and varied compositions in Marie’s cramped flat.

Then there are the director’s skills with his main actors. Called “the face of the French New Wave,” veteran performer Lafont brings maturity and intelligence to her work as Marie, nicely balancing the character’s pained awareness of Alexandre’s inadequacies as a partner with the sense that aging may underlie her reluctance to let go of him. A relative newcomer to acting, Lebrun’s hurt, and wariness are the film’s emotional cornerstone, and her phenomenal work in a penultimate scene announces her genius at sustained monologues. As for Léaud: it’s interesting to compare his work here with that in Eustache’s 1966 short “Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes.” In the earlier film, he’s subtle and restrained: a very good actor even if already famous. In “The Mother and the Whore,” by contrast, it seems to me that he’s playing Léaud-as-icon as much as Alexandre; it’s a tricky super-imposition, but somehow it works. (Near the time of this film, he starred in two other cinema milestones, Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris” and Truffaut’s “Day for Night.”)

In France, strictly historical readings say the New Wave lasted for a relatively brief time, 1957-63. But from a global perspective, wavelets from this most important and influential movement in cinema history continued to wash around the world throughout the ‘60s and beyond. While “The Mother and the Whore” is generally called a post-New Wave film, I’ve long thought of it as the movement’s last masterpiece, a grand summation of its extraordinary beauties and achievements, made by an auteur who, on the basis of this one work, today ranks alongside Godard, Truffaut, Rohmer and the other giants who narrowly preceded him.

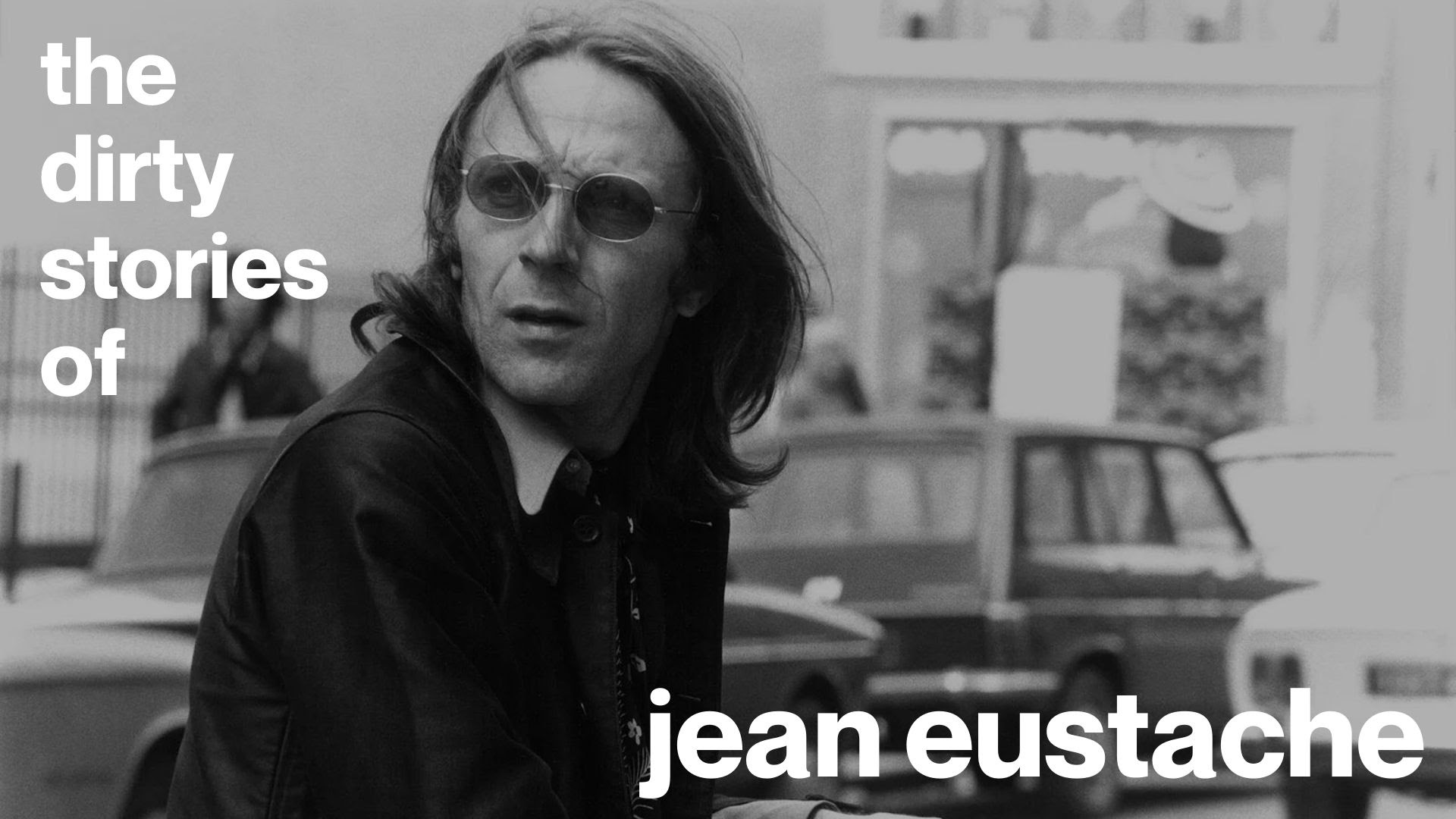

Though “The Mother and the Whore” towers over the rest of Eustache’s work, his other films have rarely been seen, which makes their current appearance something of an event, one that fans of “The Mother and the Whore” should take full advantage of. The films are grouped under the heading “The Dirty Stories of Jean Eustache,” a rather unfortunate title, at least for any viewer hoping for high-toned Gallic smut. (But read on for the title’s surprising source.) As even the title of his masterpiece evinces, Eustache’s work is rife with pairs, doubles, mirrorings, and binary oppositions—all within an essentially autobiographical framework.

Made after “The Mother and the Whore,” “My Little Loves,” his only other narrative feature, might have been titled “The Mother and the Grandmother.” It also involves an opposition between town and city. Teenage Daniel (nicely played by Martin Loeb) lives happily with his granny (Jacqueline Dufranne) in Pessac, the town near Bordeaux that’s the setting of several Eustache films, until he’s sent to the city of Narbonne and a much less idyllic life under the care of his uncaring mother (Ingrid Caven). In many ways, this is an archetypal French coming-of-age film, which is to say that its young hero does discover puppy love by the end. What distinguishes it is Eustache’s keen observation of the details of life in both places—and in between. A scene that won me over early in the film shows Daniel taking a train between town and city. Beautifully shot (in color) by the great Nestor Almendros, it’s entirely wordless but so perfectly staged and composed that it could serve as a cine-poetic miniature. The film’s title comes from a poem by Rimbaud.

If that film deserves to be paired with another Eustache work, that would be the documentary “Numero Zero,” the only other feature-length film noted here and the only one in which we see Eustache himself (albeit from the back). For two hours, the filmmaker sits across a kitchen table from his grandmother and asks her about her life. Precisely because it’s unexceptional, the feisty, diminutive lady’s narrative is enthralling. It begins during World War I when the then-16-year-old lass marries a soldier released from service after losing an eye. In the ensuing years, she makes the best of a hardscrabble life raising several kids (and losing a couple) in Pessac and other towns. But her greatest trial is a husband—a prototype for Alexandre?—whose philandering is known far and wide and eventually gets him into trouble with the law.

That infraction almost seems like the dark, private undercurrent of a public ritual that’s at the center of a pair of documentaries, “The Virgin of Pessac” and “The Virgin of Pessac ’79,” that together offer one of the most extraordinary portraits of la France profonde that I’ve ever seen. The real-life premise: in 1896, a rich man left a bequest to allow the town to annually choose and celebrate a rosière (a virtuous young woman; the word doesn’t have the sexual or religious connotations of the translation “virgin”). In 1968 Eustache took his cameras into the town hall of Pessac to observe the Mayor and the city fathers (and mothers) nominate and choose their rosière; he then shows them announcing the honor to the lovely and admirably poised young lady, followed by the communal celebration in which the town salutes her. The fact that this happened literally a month after the events of May ’68 speaks volumes about the age-old forces that doomed the dotty utopianism of the latter event. Eustache followed the one-hour black-and-white film with a color update in 1979, which shows the ritual not only has endured but has grown, prospered, and become a bit more media savvy.

Two short films paired in the series show Eustache’s confident beginnings as a narrative filmmaker. Both are droll, well-mounted, and hinge on the sexual frustrations of young men. “Robinson’s Place” follows two slightly loutish pals who spend a lot of unrewarded energy trying to pick up a young woman who eventually awards her attention to an older man who offers to dance with her. In “Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes,” Jean-Pierre Léaud is a guy on the prowl for female companionship when he discovers new opportunities for pursuit as a department store Santa Claus. Both of these black and white films follow the New Wave practice of shooting on the streets documentary style, and their views of Paris in the mid-60s are part of their fascination.

Finally, the eponymous “A Dirty Story” is a film that contains its own double. The color film begins with a man (played by the renowned actor Michael Lonsdale) sitting in front of a small group of people in a bar and recounting an experience that has had a big impact on him. He says he frequented a seedy café that had a secret: its basement had a women’s toilet with a hole in the door through which the cafe’s male patrons would watch unsuspecting females to see their genitalia (the French sexe is translated by the rather more clinical “vagina”). The man telling the story says the hole was at floor level so that the peekers had to assume the position of praying Muslims, and he chronicles the course of his own obsession and eventual disillusionment with the practice.

As strange as this is, things become even stranger when another man assumes center stage and begins to tell the same story in roughly the same words. By all appearances, this is a documentary from which the previous dramatization has been derived.

What to make of all this? As an experimental venture, the conceit of having a fiction followed by its documentary source is fascinating and endlessly thought-provoking. But doesn’t it immediately raise questions? Like, are there really peepholes in women’s toilets (floor-level or otherwise) that allow the viewer to see a woman’s genitals so clearly that they can be described in detail, as both narrators claim here? Also, both storytellers are asked, if there are situations where the genders are reversed, can women watch men? They say no, definitely not. But of course, there are such situations, only the viewers aren’t female, and the genitals can be very clearly seen—even pleasured. Are we to believe Eustache has never heard of glory holes?

This is a very weird film, one that raises more questions about Eustache and his obsession with sex than it answers.

“The Mother and the Whore” plays at Lincoln Center until July 6, after which the series continues from July 7-13.