Clifton Collins, Jr., the star of the racetrack drama “Jockey,” has riding in his blood, although the skill is so rarely called for that we’ve almost never gotten to see him do it. Born Clifton Gonzalez Gonzalez, Collins is the grandson of one Western movie and TV actor, Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez, and the grand-nephew of another, Jose Gonzales-Gonzales. Collins played a small role in the Western scenes of “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” and as of this writing was a regular on “Westworld.” His “Jockey” character, veteran rider Jackson Silva, was created by the film’s co-writer and first-time director, Clint Bentley, who grew up around horse tracks because his own dad was a jockey.

This background information is by way of explaining what you’re getting yourself into when you watch “Jockey”: a film that doesn’t have much plot to speak of, that plunges you into the middle of a richly detailed world built from firsthand observations, and that unifies itself around the teamwork of Bentley and Collins. Theirs is an indie-film mind meld for the ages, on par with the work Abel Ferrara and Willem Dafoe have been doing since Ferrara got sober.

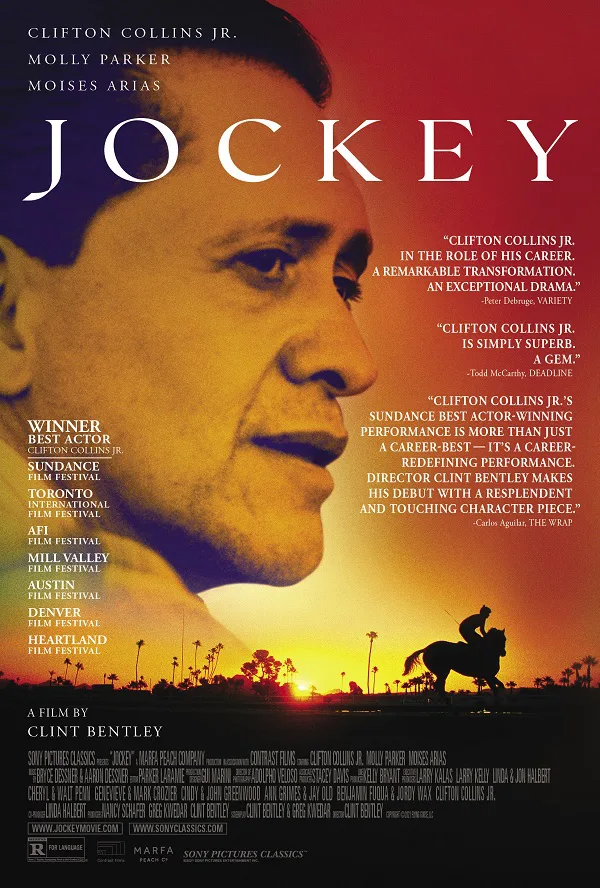

Collins is convincing from frame one. When seen in silhouette (which is often) he has the sinewy outline of a rodeo rider or caballero from old movies where men slouched with a cigarette or blade of grass between their teeth. He radiates the steely competence that Steve McQueen brought to Western dramas like “Nevada Smith,” “Junior Bonner” and “Tom Horn.” Jackson is an experienced rider nearing the end of his career. He’s macho but easygoing. He doesn’t puff his chest out trying to impress anyone, because that kind of preening calls down trouble, and he’s got enough anxiety to contend with.

There are not a lot of surprises to be found in terms of story: there’s a horse trainer named Ruth (“Deadwood” star Molly Parker) who’s been Jackson’s friend for years and seems as if she might be inclined to move things into a different category. And there’s a young new guy named Gabriel (Moisés Arias) hanging around the track. He’s about the right size to be a jockey. He eventually admits he’s been following Jackson around the riding circuit to stay close to him because (he says) he’s the product of a fling Jackson had with a woman 19 years earlier and believes it’s his destiny to join his dad’s world.

There’s also a brilliantly gifted horse, and big race coming up, and a diagnosis for Jackson that serves the same function as those scenes in all the “Rocky” movies where a doctor warned Rocky Balboa that if he got in the ring again he’d go deaf or blind or suffer brain damage or lose a kidney (or was that Adonis Creed?). What do you think a guy like Jackson is going to do with news like that? Say, “Thanks for the honesty, doc” and turn in his riding crop?

Parker and Collins have chemistry. Its peak is a long, quiet, intense conversation in Jackson’s trailer that’s an object lesson in how to make a small space feel big: by framing the setting in ways that give you a sense of what it does to a person’s energy to live alone in it, then showing how that energy changes when you add a second person with a different vibe.

You don’t watch a movie like this for plot twists. The vibe is more akin to one of those mid-career, medium-budget Clint Eastwood pictures where he played a run-down veteran of some profession or another who gave it his all and had a few golden moments but was heading into his fifties or sixties realizing that whole time he was just very good, not great, and that the main thing he has to show for all those years of hard work is a job that satisfied him.

There’s also a little touch of the sports film as practiced by Ron Shelton (“Bull Durham,” “Tin Cup“), who liked to focus on guys whose time had passed, and who never much cared who won or lost because he was always more interested in the culture of sports, and in the way athletes related to one another and to the friends, family, and supporting professionals in their little world. We don’t really see any races in this movie—at least not like in other racetrack pictures. There was no budget for that, and they didn’t want to risk injuring their star, so they find inventive ways to make the races feel like internal, emotional events, or ellipses in the story, like when soldiers in a play about war head off to battle before intermission and then come back afterward and you can tell if they won or lost by how they carry themselves.

The film was shot at a working racetrack and mixes non-actors in with pros, most impressively in a lovely scene where racers gather and discuss their injuries. Jackson sits and listens to the others describe the cost of their decision to devote themselves to a job they love and that pays little and takes so much.

This is a drama that prizes journalistic or documentary values, as well as the “epic naturalism” of films by directors like Terrence Malick and Chloe Zhao in which the camera might be as interested in flowing water, a sunset, a flock of birds, or a line of silhouetted horses as in whatever the characters are doing or saying. The score, by The National’s Bryce and Aaron Dessner, is in the same vein, using thrumming, humming, percolating soundscape effects to make it seem as if time has compressed or expanded or otherwise ceased to be measurable.

The remarkable cinematography by Adolpho Veloso uses an epic, narrow frame to convey the modesty of the characters’ lives. The shots frame the actors’ reactions and body language in a way that makes them part of the landscape rather than performers strutting upon a real-world stage. We believe that they live and work in this place, and we’ve been invited to sit close and watch them exist.