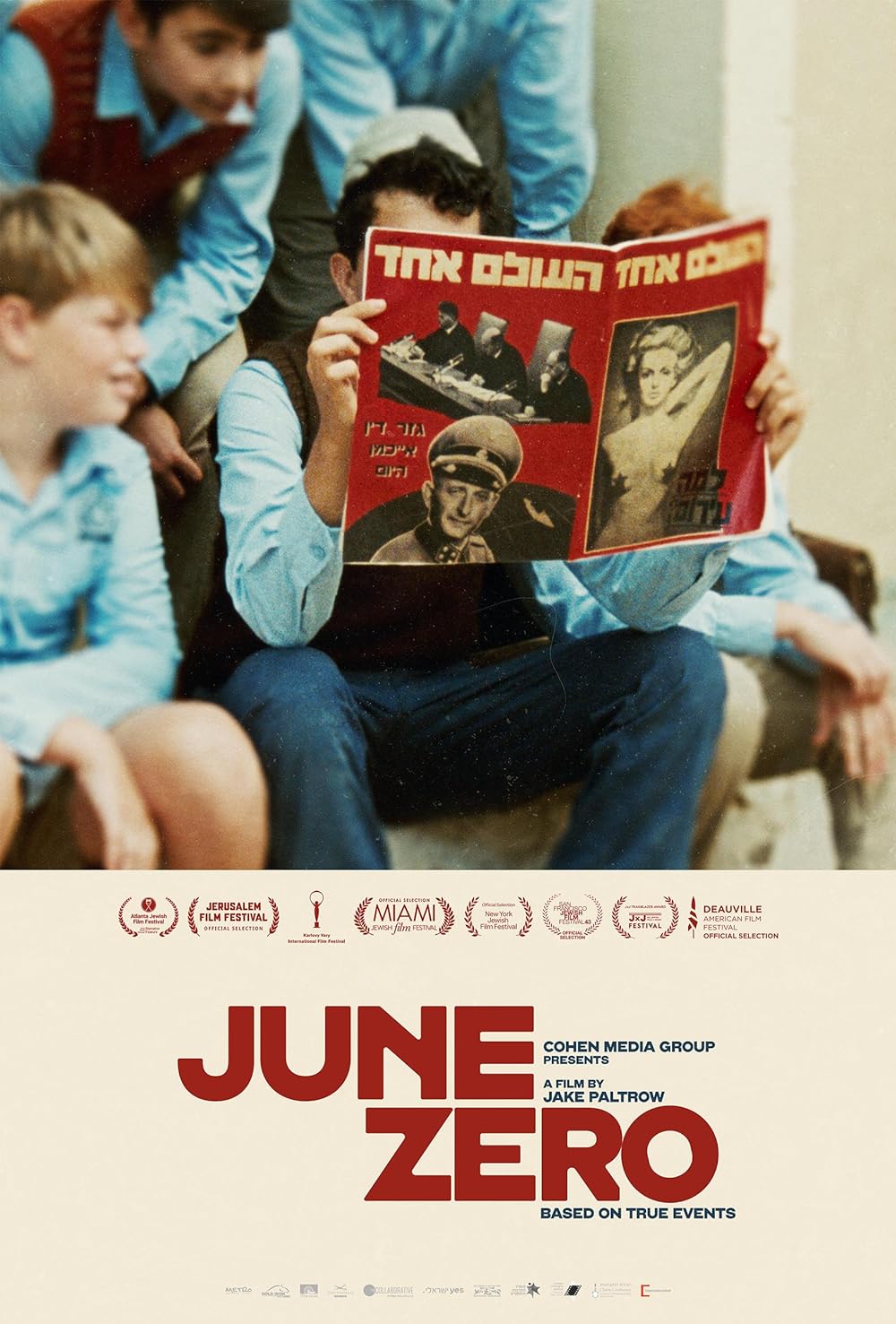

There’s no shortage of films that consider the Holocaust or Israel’s founding. But it’s rare to see the two subjects intertwined so purposely as in “June Zero.” The idea to fold it all into an anthology of interconnected short films might be unique.

“June Zero” is directed by an American filmmaker, Jake Paltrow (brother of actress Gwyneth and son of esteemed TV director Bruce Paltrow). It was conceived partly as a testament to his family’s (partial) Polish Jewish heritage. The screenplay, by Paltrow and Israeli writer-director Tom Shoval, is set in the early 1960s. It’s organized around the trial and eventual execution of Adolph Eichmann, a key architect of the Holocaust who had fled to Argentina but was captured and brought to Israel in an incident that sparked arguments about international sovereignty and whether it was ever appropriate to violate it. The dialogue is mainly in subtitled Hebrew, save for an interlude where Polish and English are spoken. It’s fragmented by nature—a work of impressionistic moments in which intellectual and philosophical ideas are considered, and powerful emotions summoned and then allowed to dissipate.

The opening story is about a young boy, an Israeli Jew, who goes to work in a factory, where he participates in the construction and cleaning of an oven for cremation. Eichmann is the one who’ll be put in it. The cremation of Eichmann is a topic of heated debate within the film. There are lines that suggest that some Israelis would gladly burn him alive if given the chance, as Old Testament retribution for what happened at places like Auschwitz. Cremation advocates also warn that having an Eichmann gravesite in Israel would encourage the wrong sorts of tourism. There are also Israelis who are uncomfortable with the eye-for-a-eye implications of incinerating a Nazi’s corpse, as well as with flouting the Talmud’s instruction that bodies be buried.

The most thoughtful and emotionally involving parts of “June Zero” focus on a prison guard named Haim (Yoav Levi), a Moroccan Jew who’s put in charge of guarding Eichmann. As explained in the movie, Israeli authorities decided that European Jews would not be allowed near Eichmann for fear they might decide to short-circuit the legal process; only Mizrahi Jews, i.e., Jews from the predominantly Muslim world, were allowed. Haim is living on a tightrope. The local press (including a reporter who seems to be a friend) craves insider reports on what’s happening in Eichmann’s cell block. A minor car crash injures Haim–not badly enough to prevent him from carrying out his duties, but just enough that he can’t completely trust the evidence of his senses, so you wonder if he’s right to be paranoid that the barber assigned to cut Eichmann’s hair will try to kill him with the scissors.

Another episode focuses on Micha (Thom Hagy), an investigator for the prosecution in Eichmann’s trial. Although he’s featured in an episode in the middle section, the movie follows him later for his own episode set in Poland, where he’s lecturing on the necessity of the existence of Israel, tying it mainly to the Holocaust. A representative of the Israeli commission (Joy Rieger) who hosts him also takes issue with his focus. This leads to a long discussion in a restaurant/bar that touches on still-sensitive topics, including the question of whether tying Jewish identity so specifically to the Holocaust is reductive and damaging in the long term (“Must never forget become only remember?”). Because there’s such strong chemistry between the two actors (and their characters), the episode seems as if it’s going to turn into a darker and more politically incendiary cousin of the “Before” films with Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke. It wisely it ends on a note that makes them seem more like representatives of certain worldviews, locked in an ideological dance.

Paltrow’s direction mostly errs on the side of naturalism—i.e., seeming to let the characters go wherever they’d go and move however they’d move in real life, rather than blocking everyone and everything to make attractive shots—and this feels like the right approach given the inherent instability of the subject. The first episode especially has a caught-on-the-fly feeling reminiscent of classic 1990s Iranian movies like “Children of Heaven” and “The Mirror.” One of the strangest, most magical things about movies is that a story like this one, in which an anxious-to-please but emotionally immature child makes a series of impulsive, bad decisions, can feel more suspenseful than a big-budget Hollywood action film about commandos trying to defuse a nuclear bomb.

The only part of the story that partly abandons naturalism focuses on Eichmann himself, who is presented like a president in a Doonesbury cartoon or George Steinbrenner on “Seinfeld”: we hear the character speak and get closeups of feet and legs and arms and hands, plus close-ups and head-to-toe shots filmed from the back, but there are no face shots. I’m guessing the intent was to maintain Eichmann as a storytelling device or “issue” while making sure that he didn’t become the main character in a film about the people his former government mass-murdered (the obscured shots also prevent us from judging whether the actor looks like Eichmann, potentially an additional distraction). Regardless, it took me out of the movie at a time when I was dialed in thanks to the script’s satirical tone (verging on “Death of Stalin” or “Dr. Strangelove” at times) as well as Levi’s superb performance as the guard. But I don’t know if there was a better way to handle this aspect of the material, short of not showing Eichmann at all.

Parts of “June Zero” are more effective than others. There are stretches where the “food for thought” aspect takes over the dramaturgy, and the movie starts to feel like an educational film. But such is the nature of the exercise. “June Zero” chose a difficult path and then walked it. It’s certainly not like anything else you’ve seen on this topic, and worth a look for that reason—also because the mostly-handheld 16mm film cinematography (by Yaron Scharf) feels out-of-time, almost as if you’re watching a lost art-house movie from thirty years ago. It respects the viewer’s intelligence. It’s trying for something.