The title of Spanish writer/director Antonio Méndez Esparza’s “Life and Nothing More” asserts to viewers that what they will witness over the next two hours won’t be comprised of tidy contrivances. In his sophomore feature effort, the filmmaker used his script merely as a blueprint, enabling each scene to be formed organically in the moment. Esparza’s aim is to capture nothing more than the relentless flow of “life itself,” a term famously selected by Roger Ebert for the name of his 2011 memoir and its subsequent 2014 cinematic incarnation.

Through Esparza’s clear-eyed artistry, scenes merely move from one to the next in a linear fashion, often stopping mid-conversation. Each one is guided by the experiences of nonprofessional actors whose performances are as assured and richly nuanced as those of any industry-branded Oscar contender. Like director Bo Burnham—who credited his 15-year-old leading lady, Elsie Fisher, as the co-author of their masterful junior high-set portrait of modern anxieties, “Eighth Grade”—Esparza seeks to understand the hearts and minds of people who are different from himself. His movie is a living testament to Ebert’s belief that cinema, at its best, can serve as an empathy-generating machine.

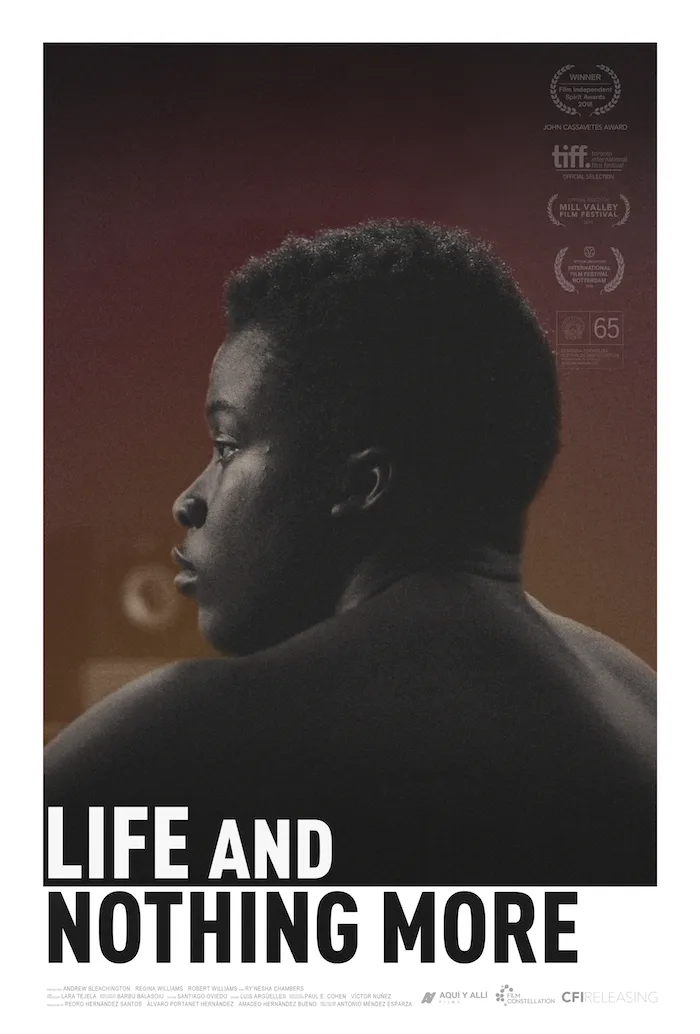

After earning Film Independent’s John Cassavetes Award during the Spirit Awards ceremony held this past March, “Life and Nothing More” is finally receiving a theatrical run in the U.S. just as the current Oscar season is heating up. Though Best Actress buzz is already favoring the expected list of familiar names, there are at least two nonprofessional contenders who deserve to be in the mix: Yalitza Aparicio, star of Alfonso Cuarón’s upcoming “Roma,” and Regina Williams, the stunning Spirit Award nominee in Esparza’s film. Many of the characters, particularly the four leads, share the same first name as the actors playing them, and Williams’ portrayal of “Gina,” a waitress struggling to provide for her children in Leon Country, Florida, is a tour de force on every level.

At first, she strikes the viewer as a volatile mess, yelling at her 14-year-old son, Andrew (Andrew Bleechington), about his failure to clean the kitchen before warning him not to wake his three-year-old sister (Ry’Nesia Chambers) sleeping in the next room. Her outburst is all the more maddening when juxtaposed with the scenes that come just before it, showing Andrew diligently taking care of his sister, bathing the girl before reading her a bedtime story where a mother voices pride in her child’s achievements. It’s only after we follow Gina during her arduous routine that we begin to fathom the mounting frustration coupled with exhaustion that fuels her rage. With her husband imprisoned on charges of aggravated assault, the woman’s high school diploma has left her with limited options regarding how to keep her family afloat. So closed off has her personal life become that she immediately deflects the advances of a kindly stranger, Robert (Robert Williams, no relation to Regina), as soon as he shows interest in her.

This leads to a wonderful scene outside her current place of employment, the Red Onion Grill, where Gina tentatively entertains the advances of Robert, sizing him up while walking around a post, at one point quipping, “Do you like pole dancing?” Glimmers of the woman’s playfulness and sensuality that had been crushed for so long under the weight of her daily burdens start to materialize here, and I found myself savoring every smile that flickered across Williams’ weary face. Editor Santiago Oviedo brilliantly links small yet crucial moments in order to provide a fully dimensional portrait of Gina’s soul, enabling us to see its many shades—tenderness, anger, humor, fierce strength—and how they drift into one another. In a shattering cut, Oviedo jumps from a tragic sequence to a mundane one, as Gina shovels ice at work, stabbing the cubes with such tear-streaked agony, one senses that she’s piercing her own heart. When Gina finally lashes out at her young daughter, we understand her meltdown entirely, considering it happens soon after she maintained a cool head during an infuriating conversation with one of Andrew’s alleged “victims.”

In one way or another, every scene builds to the film’s climactic encounter, where the boy comes perilously close to suffering the same fate as Laquan McDonald. Cinematographer Barbu Balasoiu (“Sieranevada”) surveys the action in an excruciating wide shot, magnifying the distance between a white family, playing in the park of their affluent neighborhood, and Andrew seated on a park bench with his back to them. It is the white father, fearing the safety of his pregnant wife and young child, who chooses to walk from the left corner of the frame to the right, badgering the unresponsive boy with condescending questions designed to make him leave. If Andrew had filmed the man with an iPhone, the video may have become yet another logged display of racism that went viral. Instead, he takes a more intimidating approach toward fighting back, and when Gina questions the white mother about what may have provoked her son’s behavior, the woman deliberately lies by failing to mention that her husband was trying to kick Andrew out of the park. All she can say in response is, “I’m uncomfortable.”

I’ve watched Esparza’s film twice now, and its greatness reveals itself even more upon second viewing, upending the biases we may have developed about certain characters. Even the white couple’s actions, while misguided and bullheaded, have tangible motivation not painted as purely villainous. The county where “Life and Nothing More” is set has the highest crime rate per capita in all of Florida, a statistic that engenders paranoia of all inhabitants deemed unfamiliar, even those who mean no harm. When I first saw the movie, I tended to view events from Andrew’s perspective because that was how they were framed by the camera. In a shot where he confronts Robert about a squabble he had with Gina the previous evening, the unwelcome boyfriend’s body is almost completely out of view, save for his head visible just above the surface of the kitchen counter. The staging here reflects Andrew’s own unwillingness to really see Robert for the attentive man he is, rather than the scoundrel with ulterior motives he presumes him to be. Of course, Andrew has no reason to trust any father figures in his life, and that disillusionment causes him to pick a fight that will get Robert tossed out of the house, just as the white dad starts an argument in order to remove the black stranger from the park.

All of the film’s major conflicts arise from a stubborn reluctance of its characters to communicate with one another. Gina’s generalization, “F—k all men,” that she brandishes as a shield against Robert’s sweetness, epitomizes the sort of prejudicial thinking empowered by Trump, whose impending election victory hovers ominously in the background. Without ever spelling it out, Esparza shows us how our treatment of one another as members of the same human family is a direct rebuke to the divisions enforced by tyrants to keep us frightened and isolated. In its poetic simplicity, the film’s deeply moving final shot suggests that our estrangement can be mended the moment we choose to lock eyes and listen to each other, allowing our voices to rise above the deafening cries of our presumptions. Andrew’s teacher may believe he knows the family of his student, having schooled himself in their criminal records, yet the boy is entirely correct when informing him, “You don’t.”