“Maborosi” is a Japanese film of astonishing beauty and sadness, the story of a woman whose happiness is destroyed in an instant by an event that seems to have no reason. Time passes, she picks up some of the pieces, and she is even distracted sometimes by happiness. But at her center is a void, a great unanswered question.

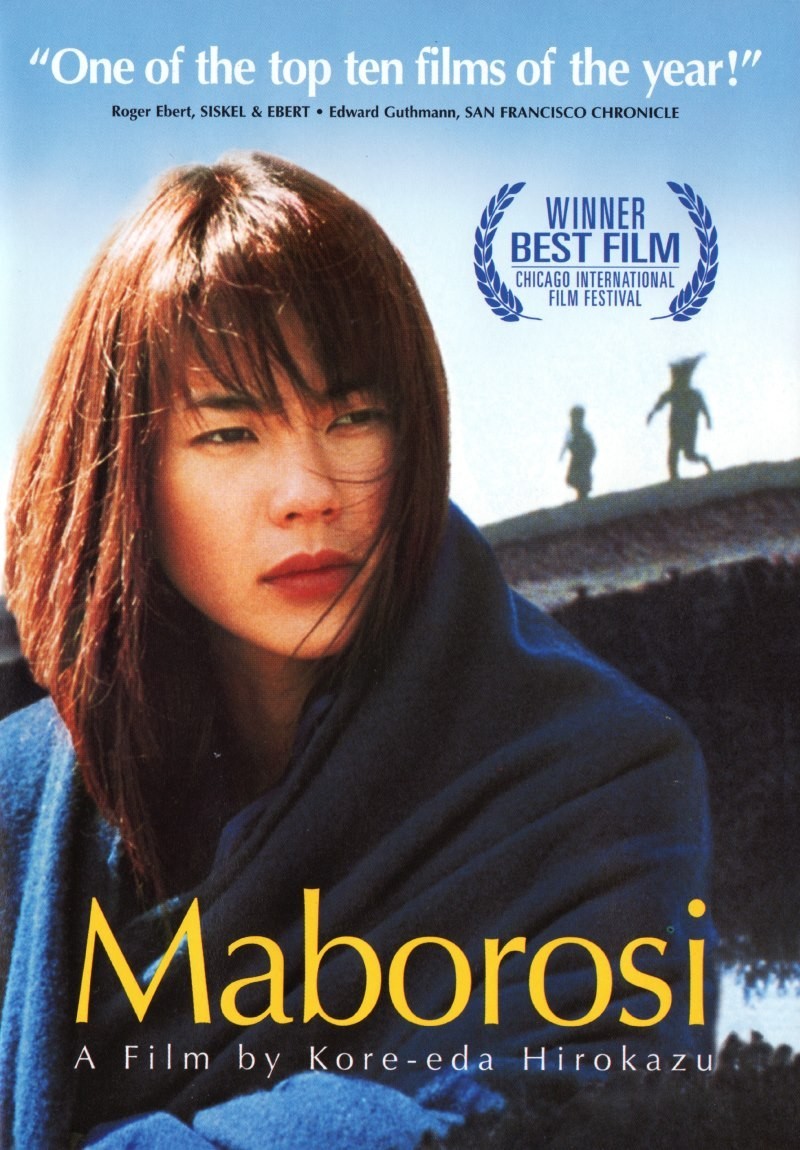

The woman, named Yumiko, is played by the fashion model Makiko Esumi. Models are not always good actresses, but Esumi is the right choice for this role. Tall, slender and grave, she brings a great stillness to the screen. Her character speaks little; many shots show her seated in thought, absorbed in herself. She is dressed always in long, dark dresses – no pants or jeans – and she becomes, after a while, like a figure in an opera that has no song.

She is 20 when we meet her. She is happily, playfully married to Ikuo (Tadanobu Asano). They have a little boy, and there is a sunny scene in which she bathes him. Then an inexplicable event takes place, and she is widowed.

Five years pass, and then a match-maker finds a husband for her: Tamio (Takashi Naito), who lives with his young daughter in an isolated fishing village. At 25, she starts her life again.

This is the first film by Hirokazu Koreeda, a young Japanese director whose love for the work of the great Yasujiro Ozu (1903-63) is evident. Ozu is one of the four or five greatest directors of all time, and some of his visual touches are visible here. The camera, for example, is often placed at the eye level of someone kneeling on a tatami mat. Shots begin or end on empty rooms. Characters speak while seated side by side, not looking at one another. There are many long shots and few closeups; the camera does not move, but regards.

In more obvious homage, Koreeda uses a technique that Ozu himself borrowed from Japanese poetry: the “pillow shot,” inspired by “pillow words,” which are words that do not lead out of or into the rest of the poem but provide a resting place — a pause or punctuation. Koreeda frequently cuts away from the action to simply look for a moment at something: a street, a doorway, a shop front, a view. And there are two small touches in which the young director subtly acknowledges the master: a characteristic teakettle in the foreground of a shot, and a scene in which the engine of a canal boat makes a sound so uncannily similar to the boat at the beginning of Ozu’s “Floating Weeds” (1959) that it might have been lifted from the soundtrack.

But what, you are asking, do these details have to do with the movie at hand? I mention them because they indicate the care with which this beautiful film has been made, and they suggest its tradition. “Maborosi” is not going to insult us with a simple-minded plot. It is not a soap opera. Sometimes life presents us with large, painful, unanswerable questions, and we cannot simply “get over them.” There isn’t a shot in the movie that’s not graceful and pleasing. We get an almost physical sensation for the streets and rooms. Here are shots to look for: The first husband walking off cheerfully down the street, swinging an umbrella. Her joy in bathing the baby. A child playing with a ball on a sloping concrete courtyard. Yumiko and her second husband sitting in front of an electric fan in the hot summertime, too exhausted to make love any longer. Yumiko, wearing a deep blue dress, almost lost in shadow at a bus stop. A funeral procession, framed in a long shot between the earth, the sea and the sky. And a reconciliation seen at a great distance.

“Maborosi” is one of those valuable films where you have to actively place yourself in the character’s mind. There are times when we do not know what she is thinking, but we are inspired with an active sympathy. We want to understand. Well, so does she.

There’s real dramatic suspense in the first scenes after she arrives at the little village. Will she like her new husband? Will their children get along? Can she live in such a backwater? It’s lovely how the film reveals the answers to these questions in such small details as a shot where she walks out her back door into the sunshine.

Underneath these immediate questions, of course, lurk the bigger ones. “I just don’t understand!” she says. “It just goes around and around in my head!” Her second husband offers an answer of sorts to her question. It is based on an experience fisherman sometimes have at sea, when they see a light or mirage that tempts them farther from shore. But what is the reason for the light?