According to a post made on social media by his daughter, Martin Mull passed away last Thursday at the age of 80 after a long illness. Beyond conveying the news of his passing, this announcement was notable for being one of the very few times when the mere mention of his name inspired something besides smiles and good cheer.

With his sharp wit, dry delivery, and flair for absurdity, Mull was one of the great comedic minds of his era. He demonstrated a keen ability to skewer the foibles of middle-class American life with such gentle precision that even those who found him mocking things they held dear still found themselves laughing at his observations. Although he may not have hit the commercial heights of some of his contemporaries, he was certainly as beloved and generated a generation-spanning fan base through decades of television and film appearances.

He was born in Chicago on August 18, 1943, the son of an actress and an engineer, and moved from there to Ohio with them when he was two. After relocating with his family to New Canaan, Connecticut, at 15, he studied painting at the Rhode Island School of Design. It’s a field in which he would eventually earn an MFA in 1967 and continue to pursue throughout his life. He even had several solo exhibitions and published a collection of some of his works, “Paintings Drawings and Words,” in 1995.

His first entry into show business came as a songwriter, writing “A Girl Named Johnny Cash,” a spoof of Cash’s “A Boy Named Sue,” for singer Jane Morgan that made it to #61 on the Billboard country charts in 1970. From there, he recorded a series of albums throughout the 1970s, including “Martin Mull and His Fabulous Furniture in Your Living Room!” (1973), “Days of Wine and Neuroses” (1975), and “Sex & Violins” (1978), and would find himself opening for such musical acts as Randy Newman, Bruce Springsteen, and Frank Zappa.

The tunes featured on those albums may have been comedic, but he presented them in a relatively straightforward manner (his 1972 debut album featured musical contributions from the likes of Levon Helm and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott). He so fully committed to the forms the songs were spoofing that it took new listeners a while to recognize that what they were listening to were inspired jokes.

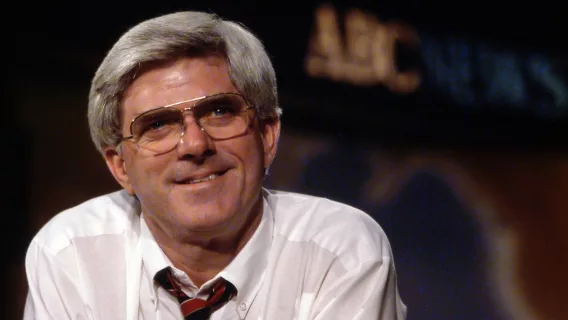

Mull would eventually shift from music to television as a vehicle for his comedy, first getting noticed for his recurring role as slimy wife-beater Garth Gimble on “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman,” Norman Lear’s absurdist soap opera spoof that became a cult sensation during its 1976-77 run. Although his character met a grisly fate—impaled by the star atop an aluminum Christmas tree—that wasn’t the end for Mull, who was then tapped by Lear to star as Garth’s twin brother, Barth, on “Fernwood 2 Night,” a summer replacement spin-off that would take the form of a local talk show hosted by him and his dim-bulb announcer/sidekick Jerry Hubbard (Fred Willard). Of course, spoofing the form and content of the typical talk show may not seem particularly radical in the wake of “The Larry Sanders Show,” “Between Two Ferns” and seemingly every third sketch on “Saturday Night Live,” but “Fernwood 2 Night” did it early and did it better than pretty much anyone else.

Much of the reason it hit as well as it did was due to Mull’s work as Gimble, effectively channeling the smug slickness that could be found in those hosting such local access shows, glad-handing local administrators as though they were members of the Rat Pack. At the same time, Mull also conveyed a certain affection for Gimble and his aspirations that kept the humor from curdling into mean-spiritedness, and the by-play that developed between him and Willard was as flat-out hilarious as anything else that was on television at the time.

Combining absurdity and satirical precision in a way that would anticipate “SCTV,” “Fernwood 2 Night” (and its 1978 revamp “America 2 Night,” which relocated the show-within-the-show to California as a way to justify more celebrity guests) was one of the great TV comedies of the Seventies—a period in which that form was flourishing like never before—. It is, therefore, doubly tragic that the shows have not been broadcast since being rerun on Nick at Nite in the early ’90s and on TV Land in 2002 and have never been released on home video. However, a number of clips and episodes (including a classic one in which the guest is none other than Tom Waits, whose tour bus broke down on the way to Toledo) can be found online for your perusal. Just make sure to block out plenty of time because, as I can tell you from experience, once you go down this rabbit hole, you will not be emerging for a long time.

Around this time, Mull also appeared in films, beginning with a turn as one of the rebellious disk jockeys battling the increasingly corporate control of their rock radio station in “FM” (1978). While the movie as a whole was somewhat underwhelming, the best moments (or at least the best ones not involving an extended guest performance by Linda Ronstadt) were supplied by Mull as the most cheerfully hedonistic of the group.

He next appeared in a rare big-screen lead role in “Serial” (1980), a social satire that saw him as an ordinary guy undergoing a mid-life crisis and trying to join his friends, family, and neighbors in Marin County, California as they plunge into one fad and trend after another in the pursuit of happiness and self-improvement. The resulting film was pretty bad—smug, condescending, mean-spirited, and startlingly reactionary in its humor, especially in its attitudes towards gays and women—and is not worth revisiting. But Mull’s turn as the hapless hero negotiating the weirdness around him was the closest thing that it ultimately had to a true satirical center.

He shifted gears to play the gently befuddled father to Chris Makepeace’s troubled teen in the cult favorite “My Bodyguard” (1980), turned up in small parts in the likes of “Take This Job and Shove It” (1981), “Flicks” (1982) and “Private School” (1983) and landed a key supporting role as Teri Garr’s lecherous boss in the hit “Mr. Mom” (1983). In “Clue” (1985), Jonathan Lynn’s farcical screen adaptation of the best-selling board game, he played war profiteer Colonel Mustard as part of a crack ensemble cast (that also included Tim Curry, Madeline Kahn, Eileen Brennan, Lesley Ann Warren, Michael McKean, and Christopher Lloyd).

Even if the resulting film did not quite add up to much in the end (partly as a result of the film’s gimmick of containing three separate endings), he and the others brought a lot of energy and wit to the proceedings that would help it to go on to become a cult favorite over the years after initially stumbling at the box-office. He also turned up as one of the many familiar faces on display in “O.C. and Stiggs,” Robert Altman’s bizarre spoof of youth comedies that was filmed and shelved in 1983, barely released in 1987, and is generally regarded as perhaps the nadir of the director’s career, even though it is more intriguing than its reputation might suggest.

Though he would continue to appear in films from time to time—he wrote and starred in Robert Downey’s filmmaking satire “Rented Lips” (1988), popped up in small roles in the likes of “Cutting Class” (1989), “Mrs. Doubtfire” (1993), “Jingle All the Way” (1996) and “A Futile and Stupid Gesture” (2018)—he would find more lasting work on the small screen. In 1984, he and Steve Martin co-created “Domestic Life,” a 1984 sitcom in which he played a family man working as a news commentator on a Seattle TV station. Although the show garnered good reviews and can be seen as sort of a precursor to “Frasier” (he even played a character named Martin Crane), viewers ignored it and it lasted only ten episodes.

He had much more success the next year with “The History of White People in America,” an often-brilliant four-part mockumentary in the style of Albert Brooks’s “Real Life” purporting to offer an anthropological examination of white culture by following the Harrisons, a family from suburban Ohio, and exploring their attitudes towards religion, sex, politics, and other cultures, often to hilariously discomfiting effect.

Over the years, he would turn up in guest bits on countless TV shows, including many of the most notable comedies of their eras—“The Golden Girls,” “The Larry Sanders Show,” “Get a Life,” “The Simpsons,” “Community,” “Veep” (for which he would receive his lone Emmy nomination for Guest Actor in a Comedy), “Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” “Bob’s Burgers” and “Grace and Frankie,” to name a few. On “Roseanne,” he had, from 1991-97, the recurring role of Leon Carp, Roseanne Conner’s gay boss/business partner who would be part of one of the first gay weddings in sitcom history (marrying a character played, fittingly enough, by Fred Willard).

He also appeared regularly as the principal on “Sabrina the Teenage Witch” from 1997-2000. He appeared in only six episodes of the cult comedy “Arrested Development” as dubious detective/master of disguise Gene Parmesan. Still, he managed to steal almost every scene he turned up in. Between 1998 and 2004, he also racked up over 400 appearances on the long-running “Hollywood Squares” game show, often in the vaunted center square position.

In terms of comedy, Martin Mull was an all-around MVP. You could give him the weakest material imaginable, and he could figure out a particular angle to it that would allow him to score big laughs despite what he may have been working with. When he worked on something on his particular wavelength—as with “Fernwood 2 Night” and “The History of White People in America”—the result was pure genius. Mull served as a comedic icon for several generations of audiences here; here’s hoping his work will continue to be seen and enjoyed for years to come.

And to whomever is responsible for its current legal absence, please do whatever you can to bring “Fernwood 2 Night” and “America 2 Night” to video and/or streaming. Lord knows we could use the laughs these days.