“You don’t know what’s going on / You’ve been away for far too long / You can’t come back and think you are still mine”—opening lyrics from The Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time” (1966)

What began as a song about an unfaithful girl trying to get back with her old flame was transformed in Hal Ashby’s 1978 Vietnam-era classic, “Coming Home,” into an anthem for those discarded souls who return from war only to find themselves hopelessly out of time. The line that concluded Ashby’s next picture, “Being There,” encapsulates the overarching theme of his oeuvre: “Life is a state of mind.” Whereas Chauncey Gardner is able to stroll on the surface of a pond, oblivious to the mortal limitations that would’ve otherwise left him submerged, the wounded veteran played by Bruce Dern is all too aware of his mortality as he walks into the ocean at the end of “Being There,” weighed down by his sense of alienation. I was reminded of this scene throughout Emmanuel Finkiel’s mesmerizing new film, “Memoir of War,” which also concludes along the seashore, as a character finds himself rendered out of focus in the eyes of those with whom he was once closest. Love may have played a crucial role in his survival, but now he must find a new reason to keep his head above water.

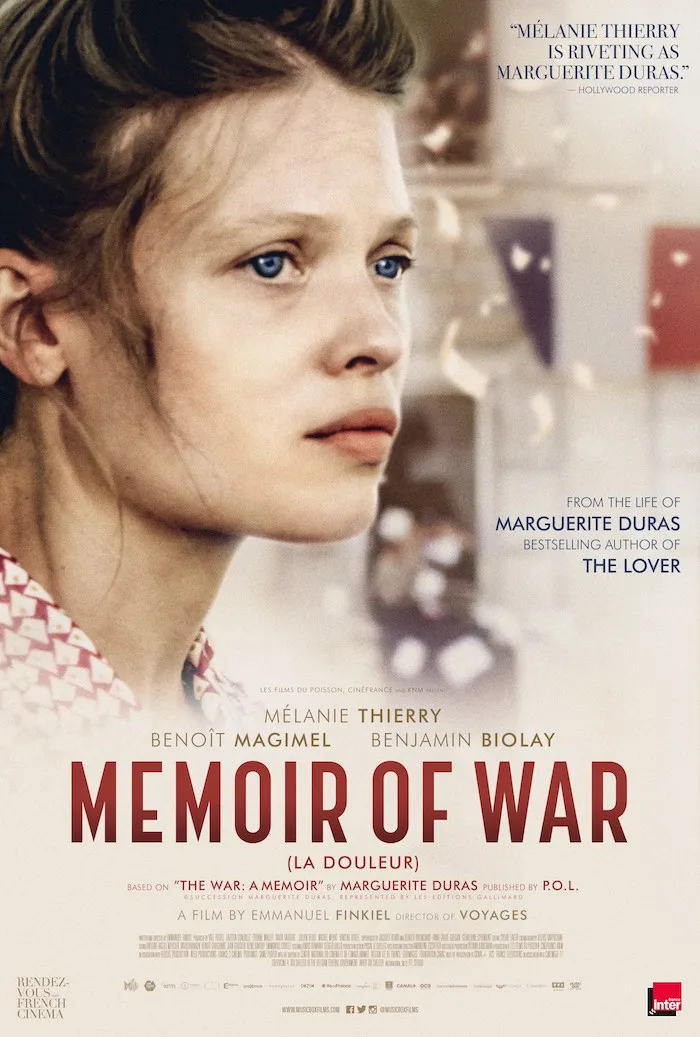

The shattering of time is a recurring motif throughout the work of Marguerite Duras, whose 1985 novel La Douleur (The War: A Memoir) served as the film’s source material. Though the iconic writer can remember the events that she recounts in this book about her life in German-occupied France, Duras has no memory of originally writing about them in the diaries that she kept during WWII. That’s hardly a surprise, considering how Duras’ work is characterized by a raw immediacy. It seems like her thoughts were somehow transferred onto the page without the added beat of putting pencil to paper. Her voice is the true star of Finkiel’s film, brought to life by actress Mélanie Thierry in narration evocative of early Terrence Malick, before his characters’ unspoken observations were reduced to monosyllabic intrusions.

Her articulated portrayal of purgatorial agony enhances each scene in a way that defies traditional exposition. As she spends nearly a full year fighting for the return of her husband, Robert (Emmanuel Bourdieu), after his arrest as a member of the Resistance, Duras finds her own inner voice fracturing into two. We hear arguments that she has with herself that echo the lovers in Alain Resnais’ 1959 masterpiece, “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” for which Duras wrote the immortal script. “You saw nothing in Hiroshima,” says the Japanese architect, to which the French actress replies, “I saw everything.” Time and again in “Memoir of War,” Duras is of two minds about Robert’s ambiguous fate, at one point contradicting her own affirmations (“I must stay alive for him.” “He’s been dead for two weeks.”).

Finkiel—a former assistant director to one of Duras’ great admirers, Jean-Luc Godard—finds provocative ways for the novel’s text to inform his film’s visual canvas. There are multiple sequences in which Thierry occupies the same frame twice, enabling Duras to watch herself from a distance, as she answers a phone or regards her reflection in a mirror. It is an indelible illustration of how the woman often feels like a disembodied spirit, hovering over her own body while pondering the surreal nature of her existence. The loss of Robert has left her ashamed to be alive, and when Rabier (Benoît Magimel), a smitten French agent working for the Gestapo, takes an interest in her, she sees him as an opportunity to get closer to her husband. After one of their encounters, the fear that pulsates through her being is reflected in the cinematography and sound design, obscuring her surroundings in order to amplify her sudden “selective deafness.”

Duras’ face is the camera’s primary subject throughout, and Thierry is a perfect fit, capturing her character’s restless intellect and world weariness without straining to be an identical match, since the author has admitted that her alter ego in the book is partly fictionalized. There are traces of Sylvia Sidney in Thierry, particularly her eyes, which convey a fierce strength amidst their sadness. Just as Sidney wielded the knife in Hitchcock’s “Sabotage,” Duras knows what she must do to rescue her husband, and though it won’t be painless or without risk, nothing will hold her back. A wonderful turning point occurs about midway through the picture, as she sits in a crowded café with Rabier, and silently realizes that she has the upper hand. With liberation on the brink of erupting outside, a group of violinists serenade the customers, as if entertaining Titanic passengers on their way to a watery grave. Duras’ relieved expression in this moment is akin to that of a woman on a doomed ship who has just found access to the sole lifeboat.

Among its many notable achievements, “Memoir of War” is one of the best films I’ve seen about the ways in which grief can pull a person in both directions simultaneously. Whereas the film’s first half plays more like a thriller, the second half proves to be an emotionally wrenching interlude perched on pins and needles. As in “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” the past and present seem to be unfolding all at once, while time appears to have halted altogether for Duras during endless days spent in her dimly lit home. She can’t bare to see reunited couples celebrating outside her window, since her husband has been deported to a concentration camp and still has yet to return. With only a few lines of audible dialogue, Robert emerges as the film’s MacGuffin, and though Duras yearns for him constantly, she is also fearful of what will happen if he is indeed alive.

Rather than answer a ringing phone that may put her questions to rest, she delays the arrival of potentially unspeakable news by fleeing to see Dionys (Benjamin Biolay), her devoted friend and fellow Resistance member who has also become her lover. Finkiel is especially discreet in how he portrays this facet of their relationship. We see it mostly in lingering glances and prolonged embraces, until Dionys wakes up to an urgent phone call in the middle of the night, and Duras stands naked in silhouette nearby. Dionys understands the complexity of his girlfriend’s pain, knowing that the physical distance between her and Robert has brought them closer together in her heart, while intensifying her guilt that they have nevertheless drifted apart. In a brief yet potent flashback, we see that the child Duras had with Robert turned out to be stillborn, a tragedy that may have irrevocably stunted the growth of their marriage. Some truths are best left implied, as demonstrated by a stunning moment early on when Duras welcomes her husband home, and walks to the kitchen to retrieve a drink for him. The camera continues to follow her down a hallway as her pace begins to slow, and the dream evaporates before our eyes without a single cut or line of narration.

In the aftermath of catastrophe, there is an innate need to reconstruct one’s reality. Biking through the post apocalyptic emptiness of Paris, freshly purged of its Nazi paraphernalia, Duras likens this new beginning to the dawn of man. It’s not long before Gaullists attempt to rewrite history by erasing all evidence that French citizens like Rabier aided Germans in the deportation and murder of Jews. It wouldn’t be until 1995, the year prior to Duras’ death, that the French government would take responsibility for the atrocities committed during this period. As we’ve seen in recent years, Poland and Ukraine are taking measures to criminalize any mention of the Nazi collaboration that took place in their countries, thus leading to a future cloaked in willful denial. At its heart, “Memoir of War” is about—to quote the architect from Resnais’ film—“the horror of forgetting,” whether it be the memory of a loved one or the faceless multitudes who fell victim to genocide. Duras insists that we remember, and there is no question her message of empathy and repentance is needed more than ever.