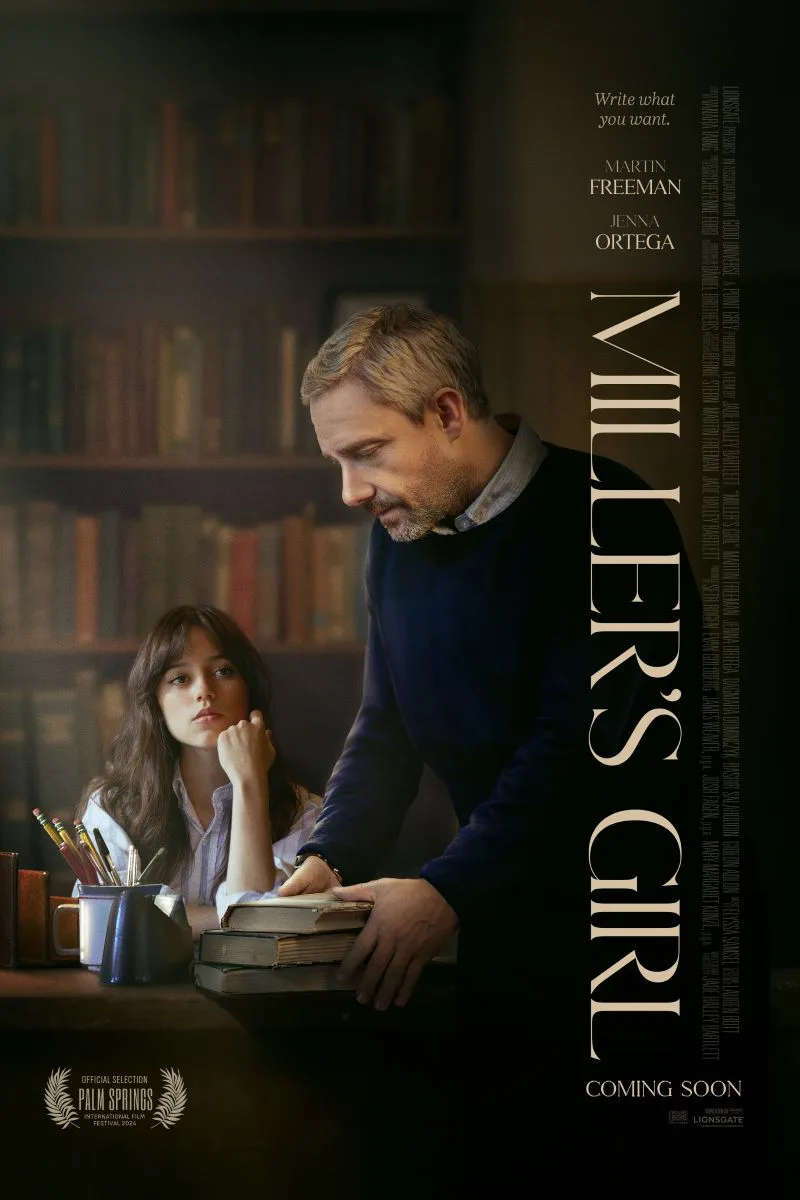

For a movie populated by verbose characters who are constantly one-upping each other with their vast literary knowledge, it seems no one in “Miller’s Girl” has read Nabokov. If they had, they would realize they’d allowed themselves to fall into a cliché and get trapped.

The debut feature from writer-director-producer Jade Halley Bartlett is dripping with Southern gothic style, as star Jenna Ortega makes clear early in dreamy, self-aware narration that spells out everything. “I am 18 and entirely unremarkable,” drawls Ortega’s character, although her very name (Cairo Sweet) suggests otherwise. “Literature is my solace in my solitude.” Cairo is a wealthy 18-year-old, living alone in her family’s Tennessee mansion; her parents are globetrotting lawyers who are gone all the time, we’re told. All she can do is laze about, smoking and scheming with her best friend, Winnie (a playful and wisecracking Gideon Adlon). She is a very alluring idea of a restless young person, wandering seductively through a misty forest in knee-high socks and miniskirts.

But whether she’s bored, seeking the approval of a father figure or a little of both, Cairo embarks upon an ill-advised flirtation with someone who truly is entirely unremarkable: her high school creative writing instructor, Jonathan Miller (Martin Freeman). You’ve heard this song before: Young teacher/the subject/of schoolgirl fantasies. But the middle-aged Miller is old enough to be her dad. He’s a failed author who turned to teaching, which his wife, Beatrice, reminds him about repeatedly. Just a little bit drunk all day in her silk nighties, Dagmara Dominczyk is very much playing a saucy, blowsy type, but entertainingly so.

But there’s a spikiness to her speech that the beautiful and wildly talented Cairo has, too. The heightened back-and-forth between her and Jonathan has a crackle to it at first, a rush of wrongness that’s irresistible. Each of them believes the other truly sees them, or at least that’s what they tell themselves to justify spending time together after class and off campus. But the kind of sharp and specific high school banter that made movies like “Heathers” and “Thoroughbreds” so invigorating quickly grows wearisome in “Miller’s Girl.” This is especially true when Jonathan gives Cairo a midterm assignment to write a short story in the style of her favorite author—and, of course, she chooses Henry Miller, purely for the provocation value. The cross-cutting between her writing the piece and him reading it in the privacy of his study, each taking turns narrating her pornographic, purple prose, is exhilarating from an editing perspective but inadvertently hilarious from a narrative one.

Through it all, Ortega is magnetic enough to keep us watching, even as her character’s motivations eventually seem pointless and inevitable. There’s a lot of Wednesday Addams in this character who’s girlish yet wise beyond her years, who’s blasé yet yearns to watch the world burn. Freeman is a sturdy presence by comparison in his cardigans and khakis, but in time it becomes clear that there’s very little to his character; a scene in which Cairo viciously dresses him down is seemingly interminable, but she’s not wrong. In one of the many vivid turns of phrase in Bartlett’s script, Cairo describes Jonathan as being “like imitation crab in gas station sushi.” That’s an image that sticks with you.

And that’s what’s so frustrating about “Miller’s Girl.” Within the muchness of it all, there are both occasionally thrilling moments and too little in terms of substance. Supporting players, including comedian Bashir Sulahuddin as Jonathan’s best friend and the school’s warmhearted athletic coach, bring some joys and surprises to this ultimately empty exercise. This could have been good trash, as my mom used to say in describing Sidney Sheldon novels, but it never comes close to reaching those heights.