“Moonlighting” is a wickedly pointed movie that takes

a simple little story, tells it with humor and truth, and turns it into a knife

in the side of the Polish government. In its own way, this response to the

crushing of Solidarity is as powerful as Andrzej Wajda’s “Man of

Iron.” It also is more fun.

The

movie takes place in London, during the weeks just before and after the banning

of the Solidarity movement in Poland. It begins, actually, in Warsaw, with a

mystifying scene in which a group of plotters are scheming to smuggle some

hardware past British customs. They’re plotters, all right; their plot is to

move into a small house in London and remodel it, knocking out walls, painting

ceilings, making it into a showplace for the Polish government official who has

purchased it.

The

official’s plan is simplicity itself: By bringing Polish workers to London on

tourist visas, he can get the remodeling done for a fraction of what British

workman would cost him. At the same time, the workers can earn good wages that

they can take back to Poland and buy bicycles with. The only thing nobody

counts on is the upheaval after Solidarity is crushed and travel to and from

Poland is strictly regulated.

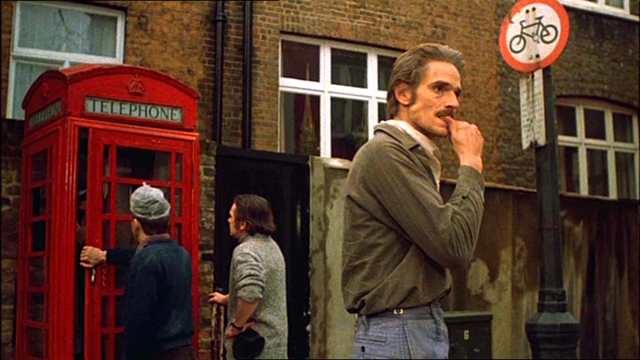

Jeremy

Irons, of “The French Lieutenant's Woman,” plays the lead in the

film. He’s the only Polish workman who can speak English. Acting as foreman, he

guides his team of men through the pitfalls of London and safely into the house

they’re going to remodel. He advises them to keep a low profile, while he

ventures out to buy the groceries and (not incidentally) to read the

newspapers. When he finds out about the crisis in Poland, he keeps it a secret

from his comrades.

The

daily life of the renovation project falls into a pattern, which the film’s

director, Jerzy Skolimowski, intercuts with the adventures of his hero. Jeremy

Irons begins to steal things: newspapers, bicycles, frozen turkeys. He concocts

an elaborate scheme to defraud the local supermarket, and some of the movie’s

best scenes involve the subtle timing of his shoplifting scam, which involves

the misrepresentation of cash-register receipts. He needs to steal food because

he’s running out of money, and he knows his group can’t easily go home again.

There’s also a quietly hilarious, and slightly sad, episode involving a

salesgirl in a blue-jeans store. Irons, pretending to be more naive than he is,

tries to pick the girl up. She’s having none of it.

“Moonlighting”

invites all kinds of interpretations. You can take this simple story and set it

against the events of the early 80’s, and see it as a kind of parable. Your

interpretation is as good as mine. Is the house itself Poland, and the workmen

Solidarity — rebuilding it from within, before an authoritarian outside force

intervenes? Or is this movie about the heresy of substituting Western values

(and jeans and turkeys) for a home-grown orientation? Or is it about the

manipulation of the working classes by the intelligentsia? Or is it simply a

frontal attack on the Communist Party bosses who live high off the hog while

the workers are supposed to follow the rules?

Like

all good parables, “Moonlighting” contains not one but many

possibilities. What needs to be insisted upon, however, is how much fun this

movie is. Skolimowski, a Pole who has lived and worked in England for several

years, began writing this film on the day that Solidarity was crushed, and he

filmed it, on a small budget and with a small crew, in less than two months: He

had it ready for the 1982 Cannes Film Festival where it was a major success.

It’s successful, I think, because it tells an interesting narrative in a

straightforward way. Skolimowski is a natural storyteller. You can interpret

and discuss “Moonlighting” all night. During the movie, you’ll be

more interested in whether Irons gets away with that frozen turkey.