Remember the guy in “Eastern Condors” with the camo green bucket hat, who never dropped his cigarette, not even after submerging his head underwater? That’s Judy Wu, aka Jack Wang or “Filter” in the English dubbed version of star/director Sammo Hung’s exuberant Namsploitation “Dirty Dozen” variant, a strong candidate for one of the best action movies of the 1980s. Judy Wu was played by Corey Yuen, a heavy smoker in real life who appeared in several milestone action movies throughout the ‘80s when he also started directing his own productions.

Yuen was action cinema’s Swiss Army Knife. His energizing fight choreography stood out in projects as varied as the epochal 1983 action-fantasy “Zu Warriors from the Magic Mountain,” for which Yuen received the Hong Kong Film Award for Best Choreography through “The Transporter” and its first two sequels. Yuen also served as an action director on everything from “Eastern Condors” to “Red Cliff,” John Woo’s two-part war epic.

In recent years, Yuen was best known as the martial arts choreographer for Jet Li movies like “Lethal Weapon 4” and “Kiss of the Dragon.” The great David Bordwell considered Yuen to be “one of the finest action directors”; Bordwell was being typically modest. Once you recognized Yuen’s work, you saw him everywhere, and if you cared about action movies, you paid closer attention. In a recent Weibo post, Jackie Chan revealed that Yuen died two years ago; his passing due to COVID-19 was kept private at his family’s request.

Yuen was one of the Seven Little Fortunes, a group of Peking Opera-trained performers whose members include Chan, Hung, and Yuen Biao. The troupe’s members were united in their talent, and Yu Jim-Yuen administered a merciless regime of training and corporal punishment. They all took Yuen’s last name as an honorific. In his autobiography (co-written by Jeff Yang), “I Am Jackie Chan,” Chan describes Corey Yuen as “one of my best friends when he wasn’t being a giant pain in the ass.” Yuen usually serves as an amiable irritant in the early chapters of Chan’s book. They talk about the differences between boys and girls, the latter of whom don’t have “little boys,” fight over comic books, and daydream about food and sex (“She’s anyone’s type”…).

Together, the Seven Little Fortunes began their movie careers as stuntmen, then bit players. Chan recalls working with Yuen and their schoolmates on early projects like “The Heroine,” a forgettable 1973 programmer that Chan simply calls “terrible”:

“Most of the movies we made back then were bad, and some of them were very bad. But all that mattered to me was the action, and for that, Yuen Biao and [Corey Yuen] and I did our best. And I loved it. I found myself enjoying the chance to make decisions and give orders, not because I liked to be the boss, but because I finally had the chance to shape the world around me[…]I’d always thought that being free meant no one telling me what to do; now I realized that it meant having the ability to control, to create, to make things happen.”

Yuen eventually stopped focusing on acting for the camera. “I never wanted to be a movie star,” he said in a 2003 LA Times profile. “I figured out right away that unless you are a really big star, it is always the director who’s in charge.” Yuen’s describing the creative freedom that Hong Kong directors were often granted by their producers, a sharp contrast to the way things were typically done on Yuen’s American and European productions. “In Hollywood, once you’ve had the meeting with the studio, everything is decided,” Yuen told the New York Times. “If you want to change anything, you have to have other meetings, and it will take a week. But the intuitions often come in the middle of doing something, so working in Hong Kong, where there’s an intuition, you can immediately incorporate it into the action.”

Yuen knew from first-hand experience that, in action movies, you lose something when actors don’t do their own stunts. That’s another unfortunate contrast between much of the Asian and US/European productions that Yuen worked on. He was never one to stand on principle and even admitted that computer graphics were “the future in action.” (From 2002, in conversation with Variety’s Wendy Kan: “Films are like clothes, you have to keep up with the trends.”)

Yuen could also make do with any genre or trend, from a “God of Gamblers” parody to a lightly horny video game adaptation. He worked with singers like Coco Lee (“So Close”), Carina Lau (“She Shoots Straight”), and Anita Mui (“The Top Bet”) and gave early starring roles to new talent like Cynthia Rothrock and Michelle Yeoh (“Yes, Madam”). Before that, Yuen made Jean-Claude Van Damme look good in his first major role as an Ivan Drago-esque villain in the 1983 martial arts trend-chaser “No Retreat, No Surrender.” Yuen also directed a young Stephen Chow in one of his first major hits, “All for the Winner,” and very literally made the Taiwanese sex bomb Shu Qi fly in “So Close.”

To be fair, Yuen’s creative decisions didn’t come out of nowhere and were rarely the exclusive result of his ingenuity. His collaborators valued his work, and while he wouldn’t have gotten far without the patronage of his fellow Fortunes, who produced some of Yuen’s best 1980s productions, they wouldn’t have continued working with him if he wasn’t so good.

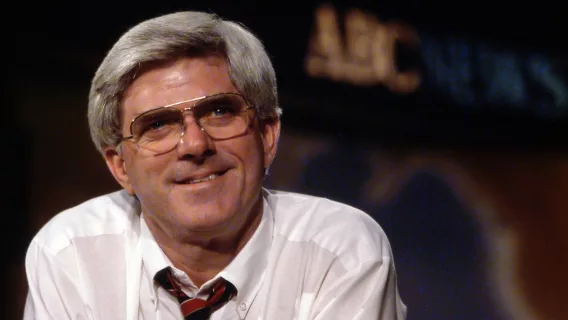

For example, Cynthia Rothrock received her first big break in the Yuen-helmed 1985 buddy cop thriller “Yes, Madam,” which was so successful that it led to a three-picture deal with Golden Harvest and the start of what became known as the “Girls with Guns” genre of Hong Kong action. Rothrock credits Yuen with her discovery, though “Yes, Madam” producer Sammo Hung first sought her out after he saw her interviewed on “World News Tonight with Peter Jennings.” Working with Yuen was demanding, as were Rothrock’s successive Hong Kong productions. “It was much easier to do Western films than the Hong Kong ones,” Rothrock told The Action Elite’s Nathan Phillips. “The action was not as extreme, and I had a script to study something I never had in Hong Kong.” Rothrock also told Phillips, as recently as 2015, that “My wish is to still today get in an A-listed movie or work with Cory Yuen again on another production.”

Yuen was as inventive of an action director as Chan, Hung, or Yuen Biao, even if he was never as famous. His work spoke for him, even if his projects weren’t always great showcases of his talent. You could still see his knack for ingratiating, gonzo choreography as early as “Ninja in the Dragon’s Den,” his 1982 directorial debut, for which Bordwell praised Yuen’s “‘precisionist’ approach that elaborated the action in depth and in unusual widescreen compositions.” Yuen developed significantly as a filmmaker after that, though you couldn’t always tell given how needlessly over-edited some of his recent work became.

It’s not purely coincidental that many of Yuen’s best movies as a filmmaker were the ones that were also produced by fellow martial artists, like “Fong Sai Yuk,” aka: “The Legend,” Jet Li’s first hit for his short-lived production company and maybe his most purely pleasurable star vehicle after “Once Upon a Time in China.” “Fong Sai Yuk” was also one of a handful of Jet Li movies to be re-edited, redubbed, and retitled by Dimension Pictures in the 1990s, including “Bodyguard from Beijing” (“The Defender”) and “My Father is a Hero” (“The Enforcer”).

Li brought Yuen with him when he came to America for “Lethal Weapon 4” and continued working with him as a martial arts choreographer on movies that would not otherwise warrant your attention (Sorry, “The Expendables” fans). It didn’t matter what kind of project it was or how good its filmmakers’ were—Yuen’s contributions stood out, even when producers, editors, and/or directors didn’t know them well enough to turn him loose. Action fans still came to recognize his name and hail Yuen for his dynamic, playful work, some of which were higher-brow than others. I can’t think of a funnier or a more fitting compliment for Yuen’s ignoble genius than the opening lines of Jeannette Catsoulis’s review of “Dead or Alive: DOA,” his goofy but thrilling 2006 video game adaptation:

There was a time when movies like ‘DOA: Dead or Alive’ lurked sheepishly at schoolboy height on video store shelves, spines straining to accommodate the charms of their actresses. But the multiplex is a beast that needs constant feeding, and sometimes the meal has to be cheese.

Yuen was never better than cheese, and his accomplishments as an action filmmaker are all the more impressive for it. His movies aren’t uniformly good, but his talent often shone through them anyway. He wasn’t an unsung genius, nor was he just your favorite action star’s favorite choreographer—Corey Yuen made you sit up every time the stars aligned, and he was allowed to make things happen. He’ll be greatly missed.