For decades, Ousmane Sembène has carried the burden of being a representative for an entire continent’s cinema: essentially the only known African filmmaker in Europe and the West and, even given that, his entire body of work is only familiar to a small handful of scholars and fanatics. There are manifold explanations for how little we are exposed to Africa’s cinema, ranging from harsh economic verities, the prohibitions of colonial powers against Africans making films for Africans, war, and then the darker intimations of prejudice: the simple disbelief that anything of cultural sophistication might emerge from a place quickly-branded by its exploiters as the “dark continent.” Sembène said, “If Africans do not tell their own stories, Africa will soon disappear.” The labor of preserving a humanistic history of Africa fell on the shoulders of this man born in 1923 in Ziguinchor, Senegal. In celebration of Sembėne’s centennial year, Film Forum is presenting a two-week retrospective of the master’s work, running September 8th through the 21st.

Sembène said he wanted to be French as a child and fed on the literature of the occupier. When he discovered stories of his own people at the age 17, he rededicated himself to being the spark to light the world to his corner of it. “I do it because I want to talk to my people,” he said, but the rest of the world was listening in the conversation with the legacy of his place and his ancestors. After an idyllic childhood in what he would call “vagrancy,” he became a dockworker and traveled to Marseilles, where he suffered an incapacitating injury. During his convalescence, he educated himself. He taught himself to read French, and when he could get out of bed, he gorged himself on European literature, music, and fine art to find inspiration and a mission in it.

There was a jagged hole in the shape of his continent in the world’s conception of art, and Sembène meant to fill it with color and life. There may be no more essential nor immediate a conduit to a culture’s entire history than the cinema, and Western depictions of Africa have painted it as untamed—marked more by its wildlife and the kind of backward primitivism ascribed to its people that most benefits a colonial perspective. After finding his fame, Sembène said, “Africa is not only about animals, trees, and men. Africa is her conception of life, her philosophies, her stories.”

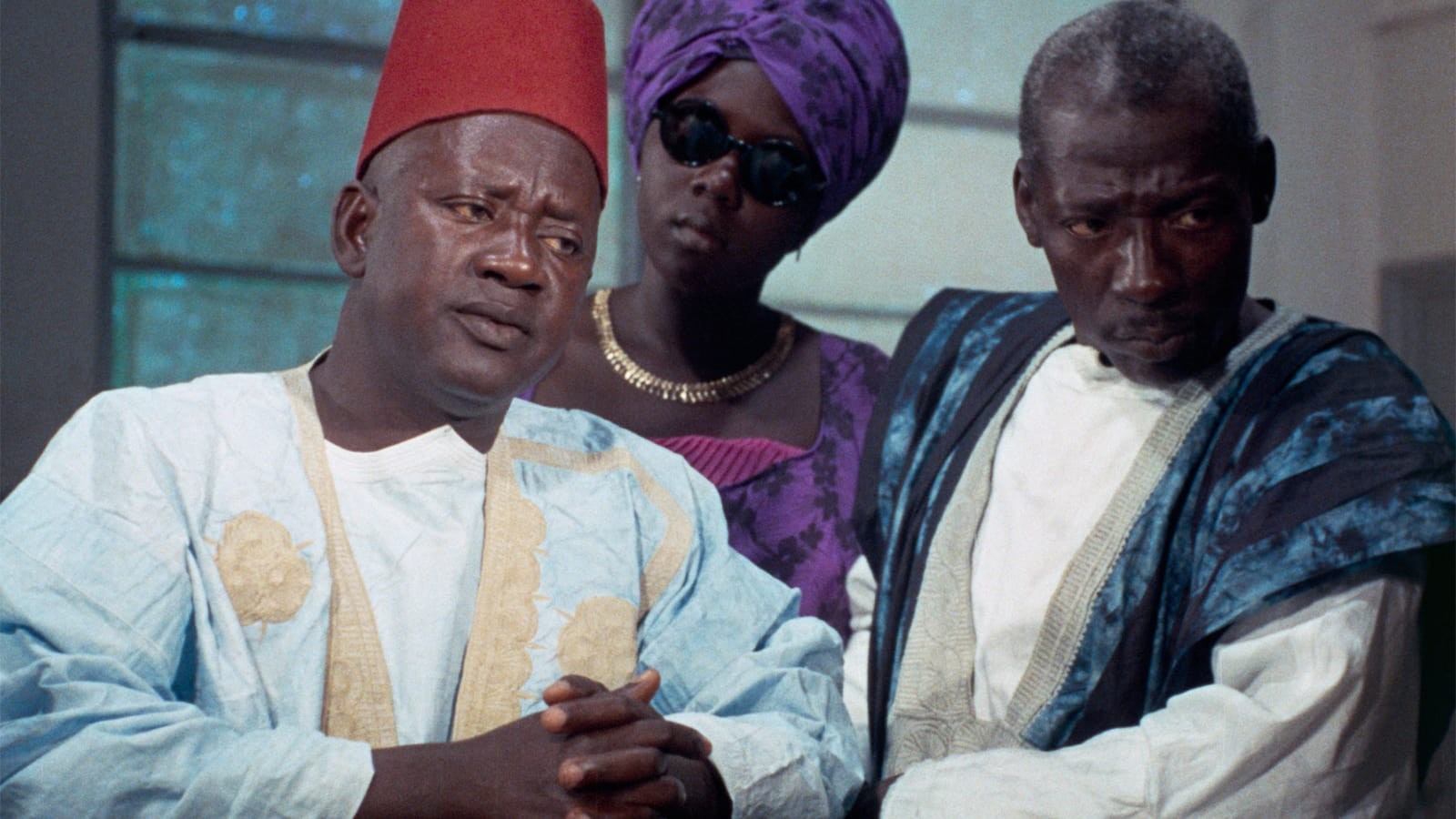

In the exact middle of Senegalese master Ousmane Sembène’s “Xala” (1975)—the multidisciplinary artist’s adaptation of his blistering novel that was itself a culturally localized take on Aristophanes’ Lysistrata—a searing song of praise by legendary xalamkat Samba Diabaré Samb blazes across the soundtrack. A group of poor, physically disabled, and otherwise disadvantaged people march across a blasted yellow plain. Samb wails about “the mighty of the world” who, despite unimaginable hardship, employ their “heart and mind” to the welfare of those unable to care for themselves: a song of praise applied in a context that immediately suggests irony or mockery. As it turns out, in Sembène’s hands, it’s neither irony nor mockery but rather a wry commentary on the audience’s—our—prejudiced preconceptions.

In the next scene, the group of “unfortunates” shares a loaf of bread, a can of condensed milk, and enough coffee to go around as they work together to curse powerful Senegalese businessman El Hadji Aboucader Beye (Thierno Leye) with impotence for accepting bribes from a French colonial power that has given lip-service to bestowing upon their colony freedom and self-governance. In truth, briefcases full of money are exchanged before the ink has dried on their noble agreement. Sembène lavishes attention, his love, on images of hands breaking bread, on the careful mixing of drinks, and concern that even the weakest among them are comfortable. It is his hallmark, these human interactions, functioning as much as a marker for his cinema as Yasujirō Ozu’s “pillow shots” or Martin Scorsese’s needle drops. He employs them here—these love notes to his country—to contrast the essential goodness of the ordinary people, this tantalizing possibility for egalitarian socialism built on kindness and empathy, and the venal cupidity and corruption of the wealthy ruling class of any color or nationality. He is as gifted a satirist as Luis Buñuel.

Sembène breakthrough was “Black Girl” (1966), based as many of his films were on his prodigious output as a novelist and historian. It follows the plight of young Senegalese woman Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), who works in France for an abusive, bourgeoise, white French couple. Succinct and uncompromising, its impact is as cruel and edged with unmistakable purpose as a fable. “Black Girl” details the power imbalance between master and enslaved, the immediately toxic influence of wealth, and the dehumanization of the exploited. For all of his career, he would return to these themes and remain progressive regarding women.

As Diouana’s situation disintegrates and her despair rises, Sembène places his camera inches from her face as she hides from a beating in a closet. In her desperation, she looks upwards at something that always reminds me of religious genuflection, an appeal to a higher power for guidance in her moment of crisis. At this moment, she is beautiful. She is the crystallization of all the pain of her people, victimized by the people of Europe and the United States for their leisure and unchecked wealth accumulation. She understands in a thunderbolt how her deliverance can only be won at her own hand.

Sembène was a great activist, a man of extraordinary contradiction who brooked no dissent in his ferocious drive to speak truth to power on behalf of, yes, his people but also, I think, the shame of his colonial indoctrination as a child. His work has the sense of a man spending his life redressing his own betrayal, however innocently, however inevitably, of his own identity. He stole resources promised to younger filmmakers to make the incendiary war film “Camp de Thiaroye” (1988), an act that fomented deep resentments amongst his colleagues, a younger generation of African filmmakers looking to come through the door “Papa” Sembène had pried open with the powerful thrust of his righteous evangelism. How does one begrudge the “Father of African Cinema” the right to wield his instrument? His legacy might have been secure, but he didn’t make another film for over a decade. As Sembène was eventually met with censorship from his own country for “Ceddo” (1977), a picture critical of Christian and Muslim attempts to appropriate African traditions, and then France for “Camp de Thiaroye,” he was asked if his frankness was his downfall: “That’s my freedom, not my downfall,” he said. And then he said it again like a chant against evil.

In the gap between “Camp de Thiaroye” and “Guelwaar” (1992)—an exiling, though he would never call it nor probably think of it as such—he came to the United States on a university tour where he became aware of the legion of admirers he’d developed overseas: Spike Lee, Angela Davis, actors and filmmakers, activists and intellectuals. His films shifted again now, back towards a sober introspection into the African character. This is the great, flawed man forced to reconsider his fear of obsolescence—fear that the important work of his lifetime had failed, his cries had been ignored, and the unimaginable human poetry of his people had been mistranslated into nonsense and oblivion.

His last films are no less angry but the work of the rare rebel who has survived to consider his legacy. His great “Guelwaar” (1992) is an intimate exploration of personal faith and responsibility, a companion piece to “Ceddo” that plays like the sober autopsy of how the events of that film went so mortally wrong; his “Faat Kinė” (2000) is an eye-popping, kaleidoscopic visual and emotional essay of how a powerful woman entrepreneur functions as the glue for the past and the herald of the future. His “Moolaadė” (2004), one of the finest films of the aughts, tackles the unspeakable horror of genital mutilation and the quotidian repression of female sexuality with irrepressible verve, uncontainable outrage, and a simply devastating incisiveness.

Whatever the era, whatever the topic, Sembėne’s films are alive and formidable. He said he didn’t want to make movies that were merely entertaining, but his movies are always entertaining. His empathy for his characters is evident in the space he allows them to exist as fully-formed, thinking, feeling beings. When they listen, watch how they listen with their whole bodies. Watch the crowd of women assembled in “Moolaadė” to witness a public whipping, lifting their shoulders in helpless sympathy, anticipating every blow like it was headed for their shoulders. Watch how the deliverer of the beating starts to cry when he understands finally that while his victim is literally only one person, the scars of his violence will be carried by everyone who has witnessed it … and meted it out, this day and all the days that have passed and are to come.

Sembène’s work is in the details of the places and the complexity of the people who populate them. They are a reckoning with our mistakes, and they hope that the universe might forgive us if we could only recognize the suffering in whom we perceive to be the least of us as equivalent to the agony experienced by any of us. Roger Ebert once called movies a machine for empathy, and Sembènė is among its greatest purveyors of refining the concept of empathy, “sonder.” Sembène forced the world to see his small portion as equal in complexity, depth, and humanity.

Embrace this rare opportunity to see Sembėne’s “protest trilogy” in new 4K restorations: “Emitai” (1971), “Xala” (1975) and “Ceddo” (1977)—the rarely-screened “Mandabi” from 1969, the first film shot in his native Wolof language and the first film at all shot in a West African language—the searing “Black Girl” (1966) that has lost none of its power. A program of short films includes his first-ever effort, “Borom Sarret” (1963), about a tough day in the life of a cart driver; it is as essential as his most controversial work.

For my money, his most openly, aggressively nihilistic picture, “Camp de Thiaroye” (1988), showcases an artist fully consumed by his rage at the suffering of Black bodies for the entertainment and advancement of white men. I think of Sembėne’s work as generally hopeful in the way any eloquent resistance is hopeful. Things don’t always work out for his characters; tragedy is a color he paints with prolifically. But it’s only in “Camp de Thiaroye” that I could find no relief from the despair of systems designed specifically to elevate one race over another. I wonder if the decade Sembėne spent in the wilderness after this film wasn’t also some kind of period of recovery.

Wonder now for yourself. Film Forum’s program is a marvel, an essential showcase for one of the great revolutionary artists in any artistic pursuit in the modern conversation. Sembėne was, in all ways, among the mighty of the world. Here is a chance to consider his life through the glorious expression of his hand and eye.

SEMBÈNE, a two-week retrospective, runs at Film Forum from September 8 – 21. For more information, including tickets and showtimes, click here.